O My Country. How I Love My Country. But do We?

David Alton – November 3rd 2017.

Professor Wheeler: thank you for that generous introduction. I hope that one day my obituary reads as well!

You made several remarks about my age when I was elected as a City Councillor and Member of the House of Commons.

It’s passing strange but when all of us were young, and were asked our age, we would tell people that we were five and a half or six and a half, and so on. As we got older we quietly dropped the reference to the half and as the years pass are likely to be more like the American comedian, Bob Hope, who famously said ’I’ve found the secret of eternal youth. I lie about my age.’

Having been a one time the baby of the House of Commons I’m going to express what may seem the counter intuitive view that we should beware of creating a cult of youth worship. Experience, courage and wisdom count for more. Qualities such as character and merit are not merely matters of age.

We should always look for individual merit – regardless of age – and even more importantly, look for those to whom we can pass on our values, our love of our country and its institutions.

But don’t let’s despise youth either.

William Pitt the Younger, in whose honour we are gathered, was elected to the House of Commons for the Appleby Constituency at the age of 21 and in 1783, at the age of 24 became the country’s youngest ever Prime Minister – serving in that high office for 18 years and 343 days.

The Rolliad – an eighteenth-century satire lampooned him for his youth:

Above the rest, majestically great, Behold the infant Atlas of the state, The matchless miracle of modern days, In whom Britannia to the world displays A sight to make surrounding nations stare; A kingdom trusted to a school-boy’s care.

Two hundred years later he was still being parodied, now by Blackadder with Pitt, the Even Younger’s mother looking for a babysitter to take the new Member to Parliament.

But at least he had graduated from being described as Pitt the Embryo or Pitt the Toddler!

It is said that William Wilberforce (himself, a few years later, the youngest member of the House of Commons) remarked to Pitt: “No one of our age has ever taken power.” To which he replied: “Which is why we’re too young to realize certain things are impossible. So, we will do them anyway.”

The very last words attributed to the no longer young William Pitt provide the title for my remarks this evening: “O My Country. How I Love My Country.” His love of his country is what motivated Pitt throughout a life devoted to public service.

The purpose of your Club is to keep fresh the memory of this great, patriotic and illustrious statesman and to attain this objective by reflecting on some of the challenges of the day and their solutions, and to encourage Pitt-like integrity, humanity, determination and judgement, in a world that is in danger of forgetting such fundamentals.

Although Pitt just made it into the nineteenth century, dying in 1806, his values and virtues are greatly needed in our own times – not least in the very institutions that he helped to shape.

Pitt died three years before the birth in Liverpool of William Ewart Gladstone – and who left office in March 1894, aged 84, as the oldest person to serve as Prime minister and the only Prime Minister to serve four terms. Gladstone, who died not so far away, at Hawarden Castle, was known affectionately as the GOM – the Grand Old Man – Disraeli said that the acronym really meant “God’s Only Mistake.”

Perhaps these two remarkable men – Pitt and Gladstone – young and old – who bookended the nineteenth century – tells us something very important about age: a thought captured well by Robert Kennedy when he said:

“This world demands the qualities of youth; not a time of life but a state of mind, a temper of the will, a quality of the imagination, a predominance of courage over timidity, of the appetite for adventure over the life of ease.”

It’s merit and qualities of character that matter, then – not being young or old.

Pitt’s farewell thought, his insistence that we should love our country, has something else in common with Gladstone – who said that “instead of the love of power we need the power to love.”

Loving and serving your country has for too many gone out of fashion – and too often we have been reduced to a sort of self-loathing. In some circles love of country has even been replaced by hate of country. We have seen this at its worst in the garb of Islamic State terrorists in Manchester and London and by IS fighters from Britain terrorising whole populations from Aleppo to Raqqa and Mosul.

Closer to home hatred of country has been magnified by the vitriol that pours out over the anti-social media into the Twittersphere.

What would Pitt have made of coarse and venomous tweets that attempt to destroy reputations and trivialise serious debate; what would he have made of toxic and often poisonous posts – sometimes promoted by interests from beyond our shores – that have become a Tier One threat to the conduct of democratic politics, to our culture and, through cyber war, even to national security?

Pitt believed that intelligent debate had to be informed debate and he spent his entire life grappling, in depth, with the great issues of his day. By contrast, we trivialise and sensationalise; we reduce complex and sophisticated arguments to 280 characters, debasing both the language and the contents – rendering nuance and shades of grey an impossibility.

In pre-electronic times Pitt insisted on being provided with objective and impartial information on which to base his judgements: not fake news or ideology dressed up as information.

But unlike his father – Lord Chatham – Pitt was not stubbornly against change and he was capable of embracing great causes – believing that evolution is always the best antidote to revolution. Pitt was not obsessed with right versus left but more interested in right versus wrong.

Look at some of today’s parliamentarians and measure them against their causes. If their only reason for going into politics is to promote an ideology or to climb Disraeli’s greasy pole they will inevitably come tumbling down. Pitt was less interested in being things than in doing things. He was the personification of public service – a concept which is neglected in too much of political life today.

I think Pitt would be deeply saddened by the multiple crises facing our great institutions. David Henry Thoreau was right when he said that “if you cut down all the trees there will be nowhere left for the birds to sing”. We need to exercise great caution before cutting down our public and political institutions – doing so will weaken the State and make us susceptible to those who seek to stoke violent upheaval and to destroy it from within. If narrow interests supersede the national interest it will lead to deep social unrest which will be difficult to contain.

In the eighteenth century, Pitt’s great rival was Charles Fox – perhaps the Jeremy Corbyn or John McDonnell of his day – and whose opinions were some of the most radical ever to be aired in the House of Commons of his era – on one occasion even dressing in the uniform of England’s American enemies; a supporter of the French Revolution; and with little interest in the intricacies of government or the responsible exercise of political power; he preferred public meetings, some as big as 30,000. He was everything that Pitt was not.

For all that, Fox was sometimes right – in his defence of liberty, for instance, his dislike of war, and his promotion of religious toleration and in his opposition to slavery.

But, if the cause was just, Pitt could be won over. Pitt would weigh the issues carefully and with great wisdom – and in eschewing revolution he could be convinced of the case for reform – supporting Catholic emancipation, administrative reforms and commercial and fiscal policies that balanced the books. He drove down debt and pursued fiscally responsible policies, living within our means, policies that would be emulated by Gladstone 50 years later.

I think Pitt would be shocked by our national profligacy and indifference to debt – both corporate and personal.

What would he make of the UK’s national debt today – which last year went well over£1.5 trillion – about 38% of GDP – with £200bn of debt amassed on credit cards, personal loans and car deals now at the same level it reached before the 2008 financial crisis? The Office for Budget responsibility predicts that unsecured household debt will reach 21% of income by 2021 – with families being pushed into destitution by the actions of loan sharks and finance companies with sky-high interest charges.

Pitt would have seen how corrosive such indebtedness is to individuals, families, communities and country and he would have said it was his patriotic duty to do something about it.

He once remarked: “You may take from me, Sir, the privileges and emoluments of place, but you cannot, and you shall not, take from me those habitual and warm regards for the prosperity of Great Britain which constitute the honour, the happiness, the pride of my life, and which, I trust, death alone can extinguish.”

Pitt had seen the country’s national debt double to £243 million during the American Civil War – with one third of the budget of £24 million used to pay off interest. He created a sinking fund which added £1 million annually to the fund so that it could pay off the interest and then the debt – which he cut to £170 million. By tackling smuggling and making it easier for honest merchants to import goods he grew the customs revenue by nearly £2 million.

With HMRC estimating that tax fraud costs the Government a staggering £16 billion every year they could take a leaf out of Mr.Pitt’s book. Think how many hospitals or homes that would build – or how it might be used to mitigate student loans – and the albatross of indebtedness that we hang around young necks.

Instead of today’s obsessive interest in fringe issues Pitt always steered the ship of State in the direction of the fundamental challenges that affected the everyday lives of the British people. Perhaps when a fox arrives at Westminster holding a placard, demanding “save the human race”, we will see the disproportionality of some of the causes we embrace.

In addition to his reputation as the man who balanced the books, Pitt also modernized the office of Prime Minister. And Pitt, a parliamentarian to his finger-tips, loved the House of Commons and was an astute parliamentarian – defying parliamentary gravity and House of Commons votes of confidence to hold his Governments together. Some of our Cabinet Ministers – as well as Opposition leaders – should consider whether, in the national interest, they should follow his example of putting the country before personal or party advantage.

By contrast we can see contemporary national disunity very clearly in the context of Brexit.

In the 2016 referendum, I was a reluctant remainer – reluctant because although I believe that what had been called the European Community served Europe well, building on the Common Market and the desirability of creating peaceful trading relations between previously warring European nations, I wholly oppose the creation of a Union that aims to create a single State.

The first political meeting that I attended was as a teenager in 1968 to hear an erudite but rather dry speaker extol the virtues of the Common Market. His arguments, but even more so the wartime experiences of my father and grandfather, clinched my support for entering the Common Market. My father had seen action at Monte Casino and in the North African desert, his brother was killed in the RAF, and my grandfather had been in the Flanders trenches and later in Mesopotamia and the Holy Land.

Siegfried Sassoon’s Great War poetry, 100 years after 20,000 British and Empire soldiers lost their lives on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, vividly recalls the horror of those catastrophic events.

Notwithstanding this, in 2007, I opposed the Lisbon treaty because it encouraged greater centralisation instead of subsidiarity – a key ideal of the founding fathers. This, in turn, had led to further bureaucratisation of the EU and the determination of elites to create a United States of Europe. This, I believe, led to the outcome last year when, by a majority of 1,269,501 votes (3.9%) people voted to leave the EU. The House of Commons subsequently voted to trigger Article 50.

Many of the votes cast in the referendum were angry votes. That anger, fuelled by a scepticism about Europe’s failure to deal with a mass migration was hardly assuaged by Jean-Claude Juncker’s arrogance in telling us that however we voted it would not make any difference. It is bad enough that millions of our poorer citizens believe that the establishment has become impervious to their concerns and their fate, but it would be unbelievably dangerous to tell 17.5 million people that they will be resisted and not listened to.

If, like Pitt, they love their country, Parliamentarians now have a duty to work in the national interest and to produce the best possible outcome for the UK. I think he would be telling MPs to get a grip.

Pitt understood that our nation has a duty to lead and that politicians have a duty to form alliances in the national interest. Pitt, I think, would have admired the European Community but not the Union and would have insisted on the ultimate importance of national sovereignty

He said, in words which are remarkably apposite today:

He also knew what marked out a great nation – eschewing the idea that self- interest and vested interest are more important than the common good. He had a high view of a politics based on principles rather than expediency.

“Necessity” he said, “is the plea for every infringement of human freedom. It is the argument of tyrants; it is the creed of slaves”

Pitt believed, as I do, that a man who loves his country does not need to debase it by remaining silent about threats to human freedom.

On Tuesday, I chaired a meeting that was addressed by a young man called Edward Leung. He is a student who helped to organise the Hong Kong umbrella protests against the increasing infringements of the rights of Hong Kong citizens – which has already led to the imprisonment of the elected “baby” of the Hong Kong legislature – and the erosion of rights gained under “two systems, one country”. Edward goes to trial in January and faces nine years in prison for peaceful protest.

Yet fearful of China, Britain has remained silent about these developments.

Likewise, in Sudan, the UK has removed sanctions and is promoting new trade deals. Yet, its President, Omar Al Bashir is indicted by the International Criminal court for genocide and Crimes Against Humanity. I have visited Darfur and the south of the country – where Khartoum still tries to impose Sharia law and wages a campaign of aerial bombardment that I have witnessed first-hand in Darfur and the South.

Or, take Pakistan. Every year we give more than £100 million in aid to Pakistan – yet they allow the persecution of their minorities – Christians, Ahmadis, Hindus and Shia – and yet we turn a blind eye, while continuing to pour in British taxpayers’ money.

From Saudi Arabia to Sudan it’s just a case of business as usual. The argument of tyrants; the creed of slaves.

No narrow or xenophobic nationalist, Pitt was always outward looking.

He was known as “Honest Billy” for repudiating the corruption and dishonesty and lack of accountability that were associated with his opponents, Fox and Lord North.

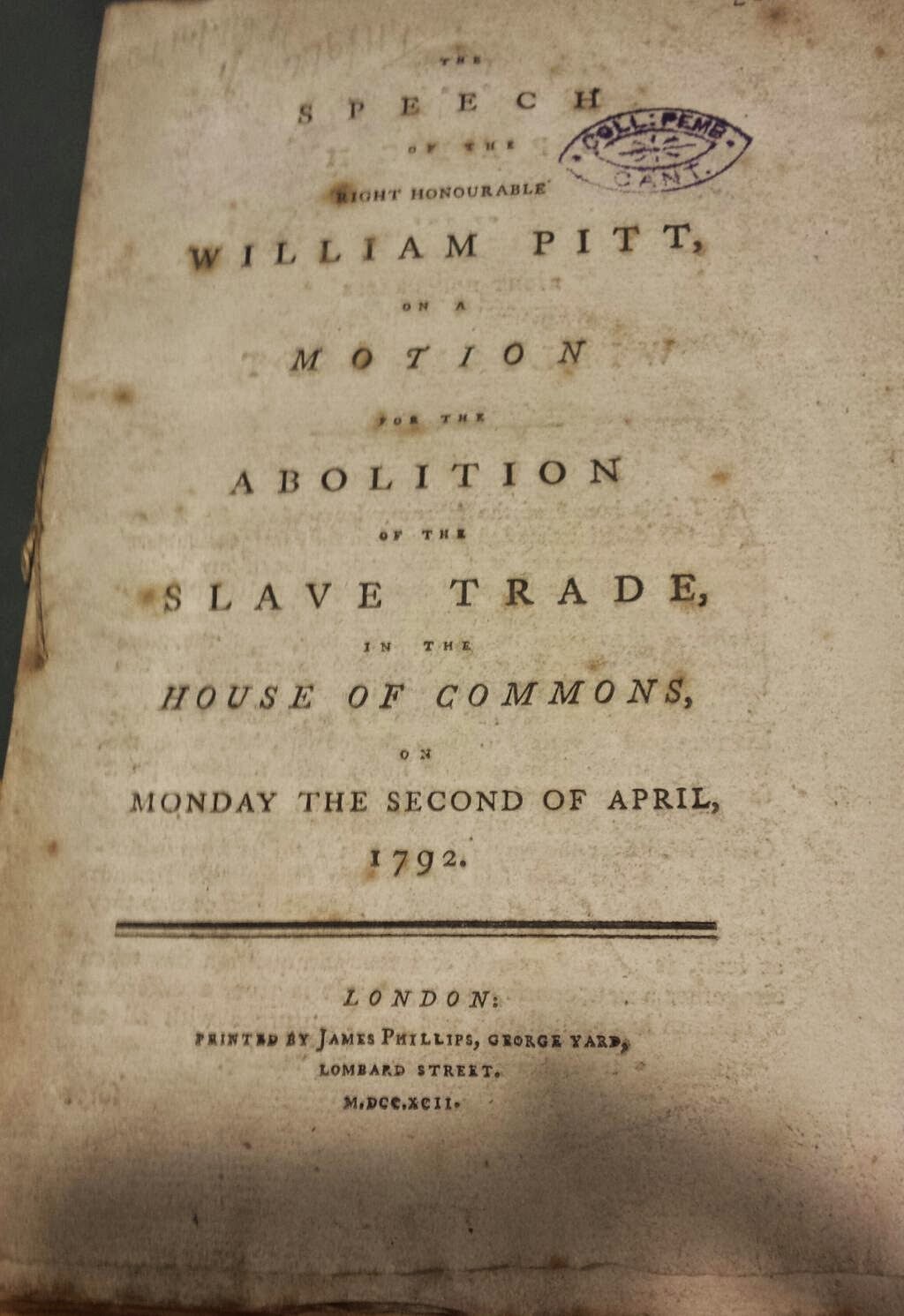

He was an abolitionist when vested interests –from Liverpool to Bristol and London – were clamouring for wealth generated by the sale of human beings as slaves. He declared “I know of no evil that ever existed, nor can imagine any evil to exist, worse than the tearing of seventy or eighty thousand persons every year from their own land.”

In speaking out against slavery he knew that he would offend the slave dealers and slave owners – and many were in his own Party. But, for him, staying silent was not an option.

Pitt was a close friend and encourager of William Wilberforce – who created the parliamentary alliance to end the transatlantic slave trade.

In the 2006 movie, Amazing Grace – which takes its name from the hymn composed by the Liverpool slave trader, John Newton – who changed his mind and joined forces with Wilberforce – there is an instructive exchange between Pitt and Wilberforce:

Pitt says: “As your Prime Minister, I urge you caution.” Wilberforce responds: “And as my friend? Pitt replies: “To hell with caution.”

Pitt would die in 1806, the year before the Transatlantic Trade was abolished, and Wilberforce was on his death bed when slavery was finally outlawed in 1833.

But these things would have not come to pass without their friendship, their partnership and persistence – changing minds, softening hearts, and enacting laws.

But their actions are also a rebuke to us in our own times – with more people enslaved than at any time in history. There are 45 million people estimated to be living in modern slavery by the Global Slavery Index. India and China are among the top five countries on that index

For every person trafficked in the UK, there are dozens of children in forced labour in Uzbekistan’s cotton mills, men and women enslaved in Mauritania, and Syrian children used as child labour in Lebanon.

I founded and co-chair the All Party Parliamentary Committee on North Korea. 90% of North Korean escapees are trafficked in China while hundreds of thousands are used as slave labour by the Kim regime.

In India and Pakistan women and children are exploited in bonded labour, and all over the world women and girls are trafficked into brothels. Recall the fatal consequences of the collapsed garment factory in Rana Plaza in Bangladesh or the plight of India’s Dalit community—so-called “untouchables”—who form a significant proportion of the 21 million people whom the International Labour Organization says are in forced labour around the world, who in total produce an estimated $150 billion in illicit profits.

I hosted a meeting in Parliament for Mende Nazer, a former slave from Sudan’s Nuba Mountains. She described how she was abducted from her home aged 12, and suffered rape and other forms of abuse while working for a family in Khartoum. In 2000, Mende was sent by her host father with false documents to work in the UK. In London, she lived as a house slave for four months at the home of a Sudanese diplomat. She was not allowed to stray further than the front door.

Mercifully, Mende was ultimately freed and now works to help others. But this is our country and our world in the 21st not the 18th or 19th century. And such modern-day slavery is a disgrace.

Let me end

Pitt may have been young but he had a deep sense of his nation’s history. He knew his nation’s story and his own place in it.

By comparison, we are a bemused generation unable to answer the question from which a television programme takes its title: “Who do you think you are?”

King Croesus the King of the Lydians asked the Oracle at Delphi what is the most important thing that a man needs to know. “Know who you are” came the answer. Isaiah cautioned the Hebrew nation: “remember the rock from which you were hewn; remember the quarry from which you were dug.”

But we are being weakened by collective amnesia, forgetting who we are and what our nation stands for. People gave their lives for our privileges and our freedoms but we are in grave danger of forgetting the sacrifices that give us our political and religious freedoms. We need to tell the old stories afresh, so that like Pitt we can pass on a love of all that we hold dear.

In the House of Commons in 1792 Pitt summed up who and what we are in these words:

“..we have become rich in a variety of acquirements, favoured above measure in the gifts of Providence, unrivalled in commerce, pre-eminent in arts, foremost in the pursuits of philosophy and science, and established in all the blessings of civil society; we are in the possession of peace, of happiness, and of liberty; we are under the guidance of a mild and beneficent religion; and we are protected by impartial laws, and the purest administration of justice: we are living under a system of government which our own happy experience leads us to pronounce the best and wisest which has ever yet been framed; a system which has become the admiration of the world.”

Pitt, then, loved his country. In our generation, the question for us is, do we?

As we reflect on his life and times let me then propose a toast and ask you to raise your glasses: “To the immortal memory of William Pitt, the Younger.”