George Bell Lecture

THE FIGHT FOR HUMANITY

As we celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Genocide Convention, is there an end in sight

There is no need to look for an artificial connection between the title of this evening’s lecture and Bishop George Bell.

The year is 1948 and the world was mourning 60 million deaths including 6 million murdered in the Holocaust. Atomic bombs in Japan, obliteration of German cities –which Bishop Bell had vociferously opposed – and the beginnings of a Cold War led in 1945 to the founding of the United Nations, and in 1948 to two seminal documents, the Universal declaration of Human Rights and the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

In the light of what is happening in the Middle East, let me say at the outset that it’s over 40 years since I went to Lebanon and urged Yasser Arafat to drop the PLO’s declared aim to destroy Israel. Chillingly, I have also visited Armageddon.

In determining how we respond to Hamas’ atrocities, recall Bishop Bell’s insistence to distinguish between the Nazis and all Germans – as we must distinguish between Hamas and all Palestinians.

And as we express legitimate fury at despicable crimes committed against Jewish Israelis by Hamas we must reiterate his urging of proportionality and his abhorrence of war crimes, whoever commits them.

But, also be absolutely clear: Any statement calling for the elimination of Jewish people – from the river to the sea – is by definition genocidal, does not constitute free speech, and brings nothing but shame and further tragedy.

What is happening today has a direct connection with events more than seven decades ago.

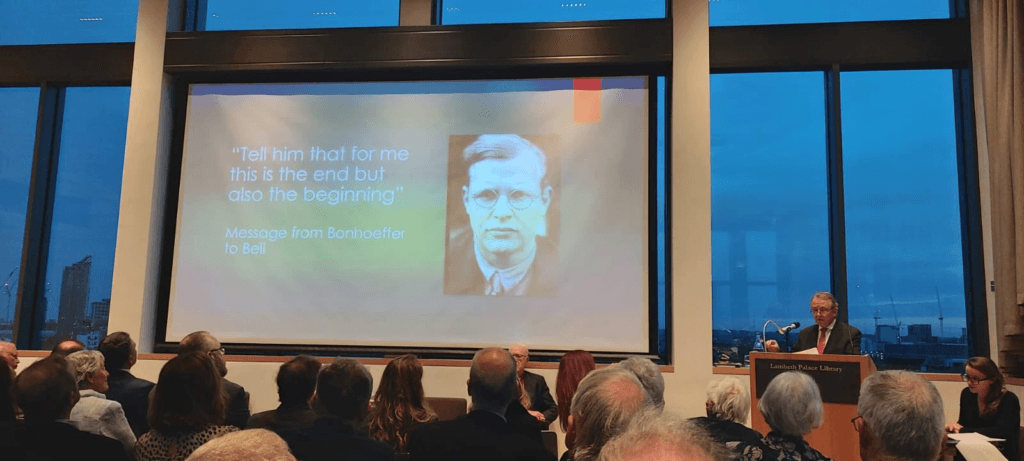

In 1945 Bishop Bell’s friend, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, had been executed by the Nazis.

Bonhoeffer had asked Captain Payne Best, a fellow prisoner at Flossenbürg to give Bell this message: “Tell him that for me this is the end but also the beginning.”

Ten years earlier, in 1935, Bell had commissioned T.S. Eliot to write “Murder in The Cathedral” and five years later Eliot composed the Four Quartets – the second of which, East Coker, concludes with the poet saying that humanity must renew itself, using the same thought, that “In the end is my beginning.”

75 years ago, the Genocide Convention was among the valiant attempts to make a new beginning

Tonight, I want to consider three things:

What was its genesis?

What does it require?

Is It fit for Purpose?

1.What Was Its Genesis?

In a radio broadcast in August 1941, Winston Churchill said there was no word adequate to describe the atrocities perpetrated by the Nazis against millions of Jews and many others including disabled people, gay people, Romanies and dissenters such as Bonhoeffer, Edith Stein, Maximilian Kolbe, Sophie Scholl, and the Munich White Rose movement.

I often think about Sophie, beheaded in 1943, at the age of 21. She once said :”One must have a tough mind, and a soft heart. Laws change. Conscience doesn’t.Stand up for what you believe in even if you are standing alone.”

Sophie’s story was well known to Raphael Lemkin, a Polish Jewish lawyer, who had seen 49 of his own relatives murdered in the Holocaust.

Like Churchill, Lemkin wanted a word which graphically and succinctly described the deadly cutting of the human family: a response to the murderous infamy of Hitler’s charnel houses.

He made a word which describes the severing of humanity, of groups of people, slaughtered because of ethnicity, religion, their identity, or difference. Hence, genos and cide – the Greek prefix genos, meaning race or tribe, and the Latin suffix cide, meaning killing.

He said it would be a word like “tyrannicide, homicide, infanticide” but “is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan … with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves.”

He said that his awareness of mass atrocities was first stirred as a 12-year-old when he read Henry Sienkiewicz’s description in ‘Quo Vadis’ of Nero throwing Christians to the lions – religious persecution often being a canary in the mine, a harbinger of far worse to come.

In 1933 Lemkin began to study and define international crimes.

He would have known of German attempts between 1904 and 1907 to exterminate the indigenous Herero and Nama people in Germany’s South West African colony.

He was shocked by and studied the fate of Armenians, between 664,000 and 1.3 million of whom were slaughtered in 1915-16 and the massacre, in 1933,of 3000 Assyrian Christians at Simele in Iraq – which I visited in 2019.

You can still see evidence of fragments of bone protruding from broken walls of what was once a police station. The site is today shamefully littered with garbage and rubbish.

At the time, Britain rejected calls for an international inquiry into the killings, cravenly arguing that that such an Inquiry might incite further massacres of Christians. Neither Simele or the Armenian Genocide have ever been recognised as a genocide by the UK and the Armenians continue to suffer to this day – with 100,000 Armenians ethnically cleansed within recent weeks from their ancient homeland in Nagorno Karabakh and the fate of the remaining 20,000 being unknown.

My own interest in the Armenians was triggered as a boy of seven when my grandfather was dying of cancer. In 1917 he had been a solider with Allenby at the taking of Jerusalem. He had kept photographs of Armenians who had been hanged by the retreating Turks, which he gave to me and which I still have.

And by a curious quirk, fourteen years later in 1972, while a student in Liverpool I was elected to the City Council for an inner-city neighbourhood where, in 1896, at Hengler’s Circus Mr. Gladstone, at the age of 86, had returned to the city of his birth to give his final speech.

He told a crowd of 6000 people that he felt compelled to come out of retirement having met “two Armenian gentlemen” – who had described atrocities – “horribly accumulated outrages” which he said, “the powers of language hardly suffice to adequately describe”.

20 years later the ignored outrages against the Armenians would become a full-blown genocide and 40 years after that would give Hitler the confidence to commit mass murder having said “who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?”

It was in this context that Lemkin wished to provide not just the word to describe the crime above all crimes but also to construct a law to give the world a new beginning.

2. What Does The Convention Require?

In State Response to the Crime of Genocide, Dr. Ewelina Ochab and I set out the fine detail of the 1948 Convention but for this evening I simply remind you of the five criteria for genocide given legal definition in Article II of the Convention

Genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group

Lemkin wanted Genocide to be recognised as an international crime and criminalised by domestic penal codes. He wanted to extend liability to a broad range of perpetrators and for genocide to be addressed by individual criminal responsibility and state responsibility.

He said “If persecution of any minority by any country is tolerated anywhere, the very moral and legal foundations of constitutional government may be shaken .”

For the UK, Sir Hartley Shawcross MP, who had been Chief British Prosecutor at the Nuremberg War Crimes Tribunal proposed to the UN Legal Committee that it should declare genocide an international crime without further review. The General Assembly did so unanimously on 11 December 1946 and the Convention followed two years later on December 9th 1948. The 153 acceding states, including the UK, agreed to duties to prevent, protect, and punish. The International Court of Justice made clear that the Convention embodies principles that are part of general customary international law.

Interestingly, George Bell had spoken against the establishment of the Nuremberg Tribunal as he believed such a Tribunal would not pass the test of impartial justice. He might, however, have applauded the 1998 Rome Statute which established the International Criminal Court and to which 123 State are parties.

Although the 1948 Convention imposed a duty to prevent it said no more than that and it would take the barbaric massacre at Srebrenica in 1995 and the Bosnian genocide for the International Court of Justice to provide such clarification in its judgment Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Serbia and Montenegro.

It says the duty to prevent arises

“At the instant that the State learns of, or should normally have learned of, the existence of a serious risk that genocide will be committed.”

To honour that duty would require states to create mechanisms to gather information and intelligence and to sound the alarm. So do they?

3. Is The Convention Fit For Purpose?

Roosevelt’s hopes of a new rules based international order – where UN blue helmets would separate warring parties and Westphalian solutions would be negotiated and adhered to – is looking obsolete and jaded – nowhere more so than in the Middle East and Ukraine.

Even measured against the remark by the UN’s most accomplished Secretary-General, Dag Hammarskjöld, that the United Nations “was not created to take mankind to heaven, but to save humanity from hell” it looks like Satan has been getting a free ride.

During the last 100 years, manmade ideology – think of Hitler, Stalin and Mao – has been responsible for as many as 100 million deaths. Add to that the brutality generated by totalitarianism, jihadism and nationalism – and the number of people who have seen their lives ended by violence is unfathomable. It has generated the mass movement of fleeing people with an unprecedented number of displace: 110 million worldwide.

Measured against the 1948 hopes of a new beginning only a fool would suggest that the Convention has achieved Lemkin’s ambitions. Never again has happened again and again.

In 1979, as a new MP, I raised the killing fields of Cambodia – where Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge killed 1.7 million of the country’s 7 million people.

In the Commons I criticised the Government’s silence during a visit to the UK by Pol Pot’s ally, Hua Guofeng, China’s Communist chairman. Even then, economics and politics determined what we say about genocide.

Think, too, of Iraq, where 50,000 Kurds were killed during the ethnic cleansing of Anfal in 1987; of Bosnia, where 100,000 Muslims were killed between 1992-1995; of Rwanda, where more than 1 million Tutsis and moderate Hutus were slaughtered over 100 days in 1994.

In a Report I wrote in 1994, I described how the Interahamwe militiamen (Interahamwe means ‘those who work together’) and soldiers arrived and surrounded the school in Murambi – which I visited – where Tutsis had taken shelter – believing French peacekeepers would protect them.

Armed with guns and grenades the Interahamwe began killing. They killed for over 6 hours. By the morning thousands of civilians were dead.

In my report I described how

“56,000 bodies were found there, and we walked from classroom to classroom, viewing 852 remains that have been disinterred. Within a few days of the massacre, a volleyball court had been built on top of one of the mass graves which, we were told, the French peacekeepers then used in their leisure time.”

Murambi is now a memorial and in the classrooms lie thousands of white skeletons, sometimes frozen in the positions they fell. It is as if a man-made Pompeii had swept over the hill and through the buildings. Some still clutch their rosaries. Some of the women were clearly pregnant. Skulls bear the marks of the machetes used to hack them down.

It takes a lot of planning to kill thousands of people. Orders must be given for roadblocks to be set up. Petrol must be requisitioned for the vehicles that transport the killers up the hill. Grenades and ammunition must be distributed to the soldiers. Avid killers need to be praised; slackers exhorted to work harder, to kill faster. Genocide is a vast criminal enterprise.

Former U.S. president Bill Clinton admitted that if the U.S. had acted on the warnings a third or roughly 300,000 lives could have been saved. Our own British officials had also been aware of the warning signs but also failed to act.

After Rwanda I travelled to Darfur and collected evidence of what has become known as the first genocide of the twenty first century: 300,000 were killed, 2 million displaced – and, basking in impunity, the same jihadists began all over again in August of this year, while Omar Al Bashir, Sudan’s former President, remains indicted for the Darfur Genocide by the International Criminal Court – but has still not brought to justice.

And, today, from Sudan, to Karabakh, to Northern Nigeria, to Burma it is very clear that the noble ideals that led to the framing of Lemkin’s Genocide Convention are largely being honoured in their breach.

I will conclude by briefly looking at four real time genocides happening today on our watch – in Iraq, Tigray, Xinjiang, and Ukraine – and use them to suggest how the Convention might be made fit for purpose and to ensure that genocide does not have to have the last word.

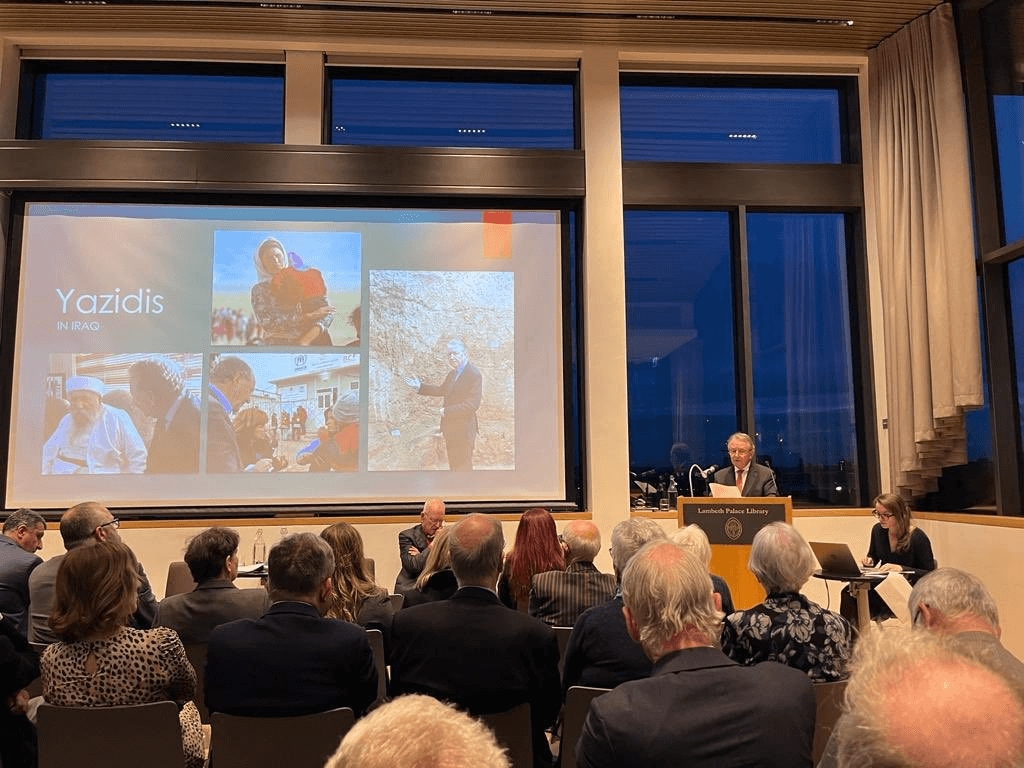

1. Iraq: The Yazidis

In 2014, ISIS unleashed a genocide against religious minorities in Syria and Iraq.

The seeds of genocide are invariably planted in a climate of indifference and impunity – with discrimination morphing into persecution and then into crimes against humanity and finally genocide. One Assyrian told me that the “persecution has become institutionalised….we feel abandoned by the international community…we feel unsafe, politically disempowered, and excluded.”

ISIS gave Christians an ultimatum to convert to Islam, pay a religious tax, flee, or be killed. In Mosul, to know who to target, they marked Christian homes with the letter ‘N’ for Nazarene and the homes of Shia Muslims were similarly daubed, with R for Reject

The Syrian Orthodox Bishop of Mosul, Bishop Nicodemus, told me “ISIS destroyed our homes, our churches, our monasteries, our dignity. They destroyed everything.”

In 2019 in Northern Iraq, I met two men whose families fled from Mosul and another whose home was burnt down in Sinjar.

No one from the international community or the Governments in Baghdad or Erbil had ever asked to meet them or to take their statements. Yet we have been told ad nauseam we are “collecting evidence “and that perpetrators will “be brought to justice”.

The late Baba Sheikh, the Yazidi spiritual leader, told me how on August 3, 2014, Daesh launched a violent attack against Yazidis in Sinjar.

Daesh fighters killed hundreds, if not thousands of men. The victims’ mass graves continue to be discovered to this day. As British Foreign Secretary, Boris Johnson said Daesh “are engaged in what can only be called genocide of the poor Yazidis” – and yet, it has taken until 2023 for the UK to recognise it as a genocide – and only now because a German Court brought in a conviction for the crime of genocide. The victims were represented by Amal Clooney.

Many other crimes go untired; including those fighters who abducted boys, to turn them into child soldiers, and women and girls for sex slavery. More than 3,000 women and girls are still missing, and their fate is unknown. I recently met British officials and asked why returning ISIS terrorists had not been investigated or charges over their role in those events.

Daesh fighters committed murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation and forcible transfer of population, imprisonment, torture, abductions of women and children, exploitation, abuse, rape, sexual violence, forced marriage, and enforced disappearance and much more -atrocities clearly matching the criteria listed as genocidal methods in Article II of the Genocide Convention.

Daesh also declared homosexuality to be punishable by execution.

There are shocking reports of gay men being tortured and killed.

In Kirkuk, ISIS executed a young Iraqi man by throwing him from the top of a building on charges of being gay. His corpse was later stoned by the crowd. Four others were executed in Nineveh.

Murder motivated by a hatred of another’s orientation, along with rape and sexual and gender-based violence, should all be considered as part of the crime of genocide.

Another gap is that political classes are also not covered by the Convention. So, ten years ago a UN Commission of Inquiry found evidence of “crimes against humanity” in North Korea but could not call the targeting of political dissenters in what the Inquiry said is “a state without parallel” a genocide – although it did leave open the question of the targeting of religious believers, who are systematically taken to the prison camps where they are tortured and killed.

These gaps in the Convention need to be filled but the case of the Yazidis suggests something even more fundamental.

In the case of atrocity crimes we must challenge the use of the veto in the Security Council to prevent referrals to the ICC and we must use ad-hoc tribunals where perpetrators attempt to frustrate accountability and justice. And we must be far more vocal in opposing the cynical creation of mechanisms for collecting evidence – like the Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Crimes Committed by Daesh/ISIS (UNITAD) and then prematurely end its mandate in 2024.

The talk now in Iraq is of an amnesty rather than justice.

What will happen to the evidence and data already collected? What will happen to victims and survivors who put their trust in the mechanism and now do not see any hope for the justice and accountability for which they long?

2. Tigray

The headline figures from Tigray are that 500,000 – 800,000 people have been killed; over 120,000 people have been subjected to conflict-related sexual violence; over a million people internally displaced within Tigray; over 60,000 Tigrayans have fled to Sudan; about 2.3 million children remain out of school and thousands of people have starved to death.

This amounts to a terrible stain on our collective conscience.

We failed to act as Ethiopian and Eritrean militias set up blockades, burnt food silos, and went from village to village committing genocidal massacres and rapes. And the atrocities continue.

The evidence is set out in a report sent to all Permanent Missions to the UN in Geneva with a call to renew the 2021 mandate of the International Commission of Experts in Ethiopia (ICHREE).

As with Iraq, the premature ending of mandates and the collection of evidence raises serious doubts about how serious we are about punishing the perpetrators and bringing them to justice.

In Tigray we failed to predict, to prevent, to protect and now we fail to punish – with such impunity opening the way for future atrocities.

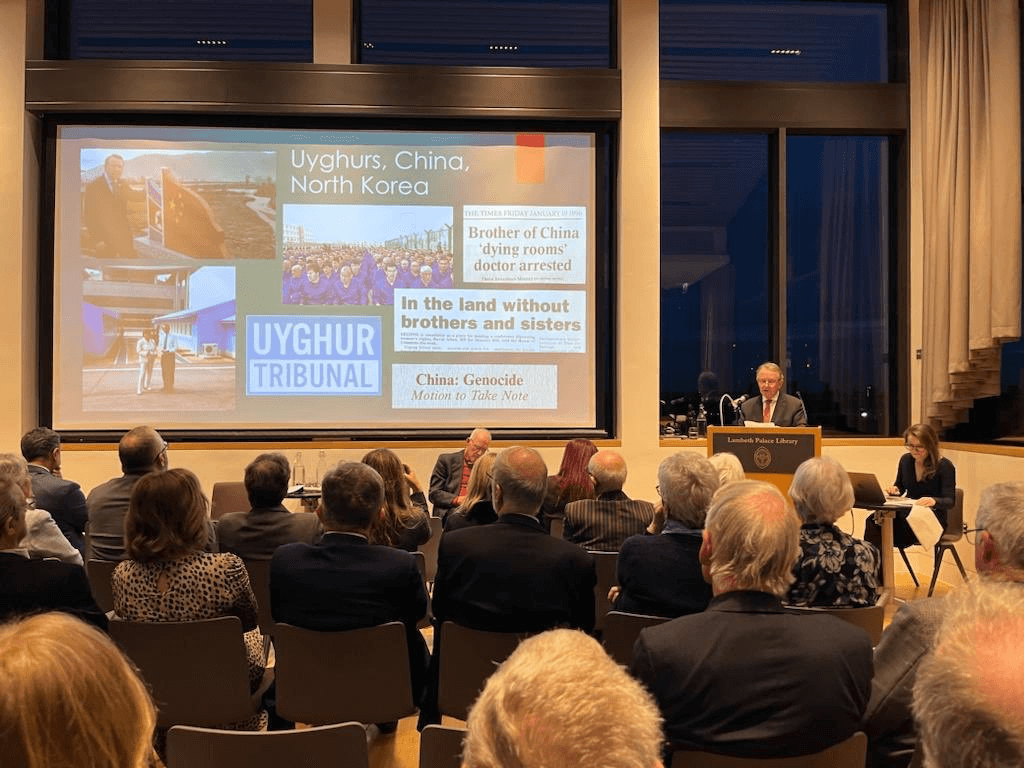

3 Xinjiang

What word comes to your mind when you hear evidence of a state involved in the destruction of a people’s identity; involved in mass surveillance; involved in forced labour and enforced slavery; involved in the uprooting of people, the destruction of communities and families, the prevention of births, the ruination of cemeteries where generations of loved one had been buried?

What word comes to mind when you hear of people being forcibly indoctrinated to believe that you, your people, your religion, your culture, never existed – and the certainty that through ethno-religious cleansing, you will cease to exist?

Those whose signature is written across these monstrous crimes know that name well, but smugly sleep content, believing that corrupted and compliant self-serving institutions and commercial considerations will keep the safe in their beds.

Through amendments to the Trade Act and other legislation I have sought to demonstrate how business as usual has been the priority even when the House of Commons, the US Administration and numerous Parliaments, the Independent Tribunal chaired by Sir Geoffrey Nice KC have declared a genocide in Xinjiang.

Genocide should be bad for business, but it has not been in the past and it is not now.

Think of Nazi slave labour and beneficiaries such as IBM and Volkswagen, which even built a labour camp next to one of its factories to ensure a supply of labour.

What is happening to the Uyghurs is comparable. Just a week ago Dr.Adrian Zenz produced a new paper on the labour camps.

Uyghurs have been forced to work in factories that form part of the supply chains of at least 83 global brands including: Amazon, Huawei, Nokia, Samsung, Siemens, Sony, and Volkswagen.

We should not accept the counterargument that trade brings liberal democracy. It hasn’t in China, Saudi Arabia, or Iran.

This is not a new debate. 200 years ago Richard Cobden, that foremost champion of free trade said free trade was not more important than our duty to oppose both the trade in human beings and the trade in opium.

My all-party amendments – which would have created a British judicial mechanism – independent of government and the vested interests which influence it – to determine whether atrocities amount to genocide – was passed by three figure majorities in the Lords but narrowly defeated in the Commons.

Such an essential change – supported by at least two former Prime Ministers – is one which will be returned to.

4. Ukraine

One of Lemkin’s indicators of genocide and listed in the Convention is the forcible transfer of children.

It has happened to Uyghur children, and it is also happening to an estimated 20,000 Ukrainian children.

Russian citizenship is imposed; they are forbidden to speak and learn the Ukrainian language; or to preserve their Ukrainian identity.

They are also illegally adopted by Russian families – with new laws that were specifically designed to speed up the process without any due attention t the best interests of the child

Last month at the UN General Assembly President Zelensky referred to the plight of the kidnapped Ukrainian children:

“What will happen to them?…Those children in Russia are taught to hate Ukraine, and all ties with their families are broken … This is clearly a genocide. When hatred is weaponized against one nation, it never stops there”.

On 17 March, a pre-trial chamber of the International Criminal Court issued warrants of arrest for war crimes, for Vladimir Putin and Maria Lvova-Belova, who has orchestrated the abductions.

One practical thing the UK could do would be to amend our law, especially the International Criminal Court Act 2001, to ensure that those responsible for international crimes and who are not UK citizens or residents can be prosecuted by British courts.

To end.

Opposite the Palace of Nations in Geneva stands the broken chair, erected in 1997. Daniel Berset intended the missing leg to symbolise the breaking of so many lives by land mines. But, for me, it is also a symbol of the breaking of humanity every time a genocide occurs. Think of the Yazidis, Tigrayans, Uyghurs, Ukrainians, Armenians – and all the others to whom I have referred. Those examples provide little cheer but on this 75th anniversary they should be a spur to complete the work of Raphael Lemkin who asked in 1939 ‘Why is the killing of a million a lesser crime than the killing of an individual?’

In asserting the importance of confronting the crime above all crimes and the place of international law let me give the final word to Bishop Bell who, in 1944, speaking in the House of Lords said “The Allies stand for something greater than power. The chief name inscribed on our banner is ‘Law’” Humanity would certainly be in a better place if 75 years later we finally made reality of Lemkin’s law on genocide.