I have written previously about Michael O’Brien’s novel, “Father Elijah” (see below). He has just published a sequel – “Elijah in Jerusalem” – which sees the central character, a Jewish Catholic priest, and survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto – continue to challenge and confront a politician intoxicated by the prospect of global domination. O’Brien is a master story teller and weaves together a classic tale of a man of faith willing to pit himself against seemingly impossible odds. Also woven into this sequel are the foreshadowing of end times but, refreshingly, O’Brien makes it clear that he despises “the tyranny of unholy fears on the one hand or self reliance on the other” and warns against personal interpretations of Scripture or the conjuring up of apocalyptic scenarios. Instead, this is a timely reminder that all our lives are lived in end times and that we are called upon to remain awake. In every generation we face spiritual dangers and O’Brien’s fugitive priest – falsely accused of murder by those who wish to silence him – has some timely warnings for each of us. As Elijah encounters fellow travellers we are reminded that whatever our weaknesses and failings there is always mercy and forgiveness. Although the politician refuses to listen others hear and the intriguing climax of the novel reminds us that even in the midst of disaster there is hope and others taking part in the same relay race.

If you haven’t encountered Michael O’Brien’s novels a good place to start is “Sophia House” – the first of the Father Elijah trilogy and in many respects the very best of his books. .

Elsewhere, he explores some very important themes – nowhere more so than in his “The Father’s Tale”. Alex Graham, a Canadian book-seller and widower, ends up tracking his missing son half way around the world. It’s a beautiful odyssey motivated by a man’s unyielding love for his prodigal son.

Add to this,”Theophilos: A Novel “ which is a fictional account of the relationship between the evangelist and doctor, Luke, and the man he writes to by name in the Acts of the Apostles and in his Gospel account and his epic novels – a series entitled Children of the Last Days – set in British Columbia – and you will have fiction to keep you on your toes for the whole of 2016. .

Apocalyptic literature have their origins in the Bible. These are stories which foretell the end times.

The prophets Joel and Zechariah, the Book of Daniel and four chapters of Isaiah (24-27)are either apocalyptic or reveal things which have previously been hidden. The prophets and apocalyptic writers all experience visions and dreams and their insights are often given interpretation by the presence of an angel revealing messages from the heavens.

Writers would anticipate the final consummation of the created with the Creator; explore the origins of evil; and the history of mankind’s eternal struggle. The bottom line is that humanity can only escape judgement if it repents and seeks a new relationship with God. Writers from the apocalyptic tradition despair of humanity’s present condition and anticipate a future world which replaces our broken and wasted dystopia.

We have to enter into this Old Testament tradition if we are to have any real understanding of the New Testament’s Book of Revelation, the final book of the Bible.

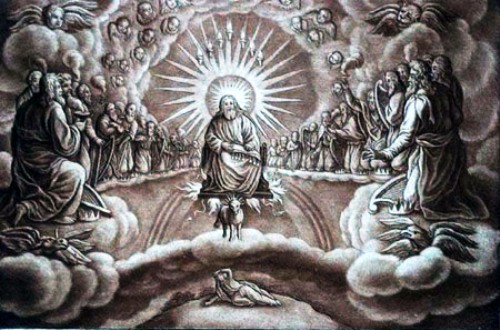

Sometimes called the Apocalypse of St.John the Divine, the Book of Revelation is characterised by extraordinary vivid imagery, symbolism, and a declaration of Divine Judgement. An angel proclaims the Revelation of Jesus Christ; there are prophesies of a new heaven and a new earth; and underpinning it all is the endless battle between God and Satan – the ultimate adversary.

We meet the twenty four crowned elders; the Lion of Judah who is the seven horned Lamb; the four living creatures; the seven angelic trumpeters; a star called Wormwood; and the four horsemen of the Apocalypse.

The modern heirs to this apocalyptic emerged in the early nineteenth century. Mary Shelley’s “The Last Man” marked the beginning of a more secular approach to apocalypse. Hers was a prophetic form of science fiction predicting a world ravaged by plague where the last man struggles to survive. It finds echoes in P.D.James’ excellent novel “The Children of Men” – where the story unravels of the last child to be born.

In “The War of the Words” H.G.Wells saw a different kind of apocalypse. This fictional violent culmination of mankind‘s story would be followed by all-too-real hideous terrors of the twentieth century, which, in turn, provoked many more works of end times fiction.

The Oxford Inklings were formed in the quagmire and gas of World War One trenches – surely leading them to believe that Armageddon was upon them. The literature of C.S.Lewis, Charles Williams and J.R.R.Tolkien was all shaped by those events and by their Christian beliefs.

Tolkien’s ” Lord of The Rings” provides an epic apocalyptic narrative – beginning with his own Genesis story of the creation of a parallel world (“The Silmarillion”) – followed by the combat which takes place between his small people, the hobbits, who struggle to overcome overwhelming and pervasive evil. Perhaps anticipating the climax of his tales Tolkien writes that “for a Catholic history is one long defeat, with glimpses of the final victory.”

A more explicit account of the last days of the Church appears in Robert Hugh Benson’s “Lord of the World”, written in 1909. A teacher gave it to me to read while I was a teenager at school.

Benson foresaw a world where the Church had either been suppressed or ignored – where despondency leads to routine euthanasia; where a one world government has outlawed national diversity; and a world leader, the anti-Christ emerges.

Almost a century after “Lord of the World”, in 1996 Ignatius Press published Michael D. O’Brien’s “Father Elijah – an apocalypse” – with themes reminiscent of Benson. The tone is set at the outset with words from the Book of Revelation: “Awake, and strengthen what remains and is on the point of death…”

O’Brien paints a picture of a church under siege – within and without. The book is about the struggle of orthodox Christianity and about the dangers of living within and relying upon our own strength rather than in the strength and love of God.

O’Brien’s hero, Fr.Elijah, is a Polish Jewish Holocaust survivor who is destined for high political office in Israel. Following the death of his young wife he embraces Christianity and becomes a monk at Mount Carmel.

The Pope calls him out of his monastic seclusion, “to strengthen what remains”, to save the Church and the world. It is a clever novel with plenty of page-turning suspense. Beyond a thrilling plot it challenges its readers to consider again the essence of faith and the way the world is heading.

“Fr.Elijah” creates an apocalyptic novel which has its conclusion in Jerusalem. Here, Fr.Elijah’s protagonists, led by an anti-Christ leader, attempt to assert their hegemony over the world. As he and his companion look over the city, O’Brien writes: “Then, with a roar came the thunder again, pealing in circle beyond circle of those tremendous Presences – Thrones and Powers – who themselves to the world as substance to shadow, are but shadow again beneath the apex and within the ring of Absolute Deity…the thunder broke loose, shaking the earth that now cringed on the quivering edge of dissolution…” and, as they sing the Tantum Ergo, the Prince of rebels makes his last appearance and is finally eclipsed: “Then this world passed, and the glory of it.”

Fr.Elijah ends where the Book of Revelation begins earning a well-deserved place in the canon of apocalyptic literature.

The Wall Street Journal – reporting the case of Jimmy Lai and the House of Lords debate

The United Kingdom and Jimmy Lai Speaking up for...