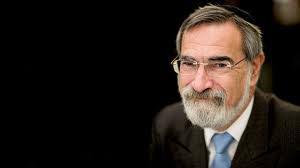

In 2009 Rabbi Jonathan Sacks – who has, sadly, died today – made his Maiden Speech in the House of Lords.

As befitted a Jewish Rabbi he began his remarks with a story laced with humour. Commenting on the close proximity of the House of Lords Chamber to the Moses Room he said:

“when I entered this Chamber for the first time, I did so from the Moses Room. I thank noble Lords for the extraordinary lengths to which they went to make a rabbi feel at home. Today, I feel the other side of that occasion, for it was Moses at the burning bush who felt so overwhelmed by emotion that he told God that he could not speak; he was,

“not a man of words”.

Mind you, that did not stop him speaking a great deal thereafter. In fact, on one occasion, when pleading with God to forgive the people for making the golden calf, he spoke for 40 days and 40 nights. However, on another occasion, when asking God to heal his sister, Miriam, he limited himself to a mere five words. I am told by your Lordships that, when making a maiden speech, it is better to err on the side of the latter than the former; and that I will try to do.”

Thereafter, whenever Lord Sacks addressed Parliament, we always knew that we would be privileged to hear a voice of reason and wisdom – with never a word wasted.

Not that this came as a surprise to me.

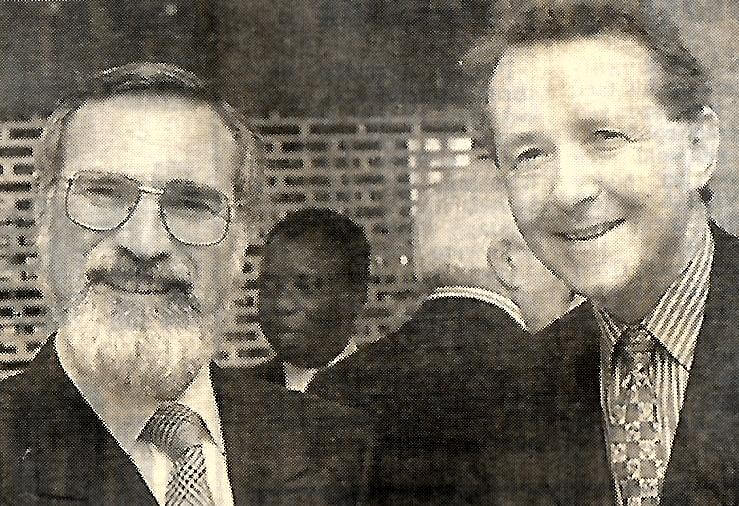

In 1998, I had invited Rabbi Sacks to speak at a Roscoe Lecture in Liverpool.

We were treated to a masterclass as he reflected on the attributes which contribute towards good citizenship and to the building of strong communities.

These were themes which he explored in his book “The Home We Build Together”. Among his other works, “The Dignity of Difference”, “Lessons in Leadership” “To Heal a Fractured World” and “Not in God’s Name” are all books with which I would not want to be parted.

Jonathan Sacks had decided views about what makes for political leadership. They should be studied carefully by all who aspire to lead: “Leadership isn’t about the leader. Leadership is about the people you lead and the cause you lead for. That’s a wonderful antidote to narcissism. In the end, the great leaders, are the people who attach themselves to something bigger than themselves and that is what really makes heroes out of people.”

Rabbi Sacks’ father – who had left school aged 14 – had come to the UK from Poland – fleeing here to escape persecution.

This led his son to fearlessly champion all those being persecuted for their faith or ethnicity and to value the safe haven Jewish refugees had reached in the UK: “many Jews in Britain know in their hearts and their very bones: that had it not been for this country, their parents or grandparents would not have lived and they would not have been born.”

This also informed his view about the sacredness of life itself:

“…issues like abortion and euthanasia, which had always been subject to an overriding sense of the sacredness, or otherness, or givenness of life, are now reduced to property rights: the right freely to dispose of what one owns, from a foetus to a life.”

In addition to championing the very right to life itself, Rabbi Sacks insisted that alternative views had a right to be respectfully heard, not least in the academy, prizing as he did, the centrality of education: “ I was religious; my doctoral supervisor, the late Sir Bernard Williams, was Britain’s most intellectually gifted atheist. Yet never once did he deprecate or even challenge my religious faith. For we were both equal participants in that collaborative pursuit of truth that Judaism’s sages, long ago, called, “argument for the sake of heaven”.

Jonathan Sacks believed that democratic freedom was not just about elections, laws and parties.

He was with Alexis de Tocqueville, who said that democratic freedom was dependent on “habits of the heart” and argued that we need the civility and willingness to hear opinions with which we disagree and that political life was dependent on “friendships that transcend the boundaries between different parties and different faiths. And those things must be taught again and again in every generation.”

What a contrast with today’s shrill intolerance and the no platforming of speakers, let alone the poisoning of universities and political parties with toxic and hateful ideologies – which Lord Sacks’ own Jewish community has itself experienced in no small measure.

Lord Sacks concluded his first speech in Parliament by urging us to keep faith with the past while honouring our obligations to the future and understanding our collective responsibility for the common good. He placed great importance on the role of education.

These were not just themes for a speech, they were the signposts which guided this wonderful man throughout his entire life.

His death now robs the Jewish community of a wonderful religious leader but it also robs the rest of us – drawn from many different backgrounds – of his sane and compassionate voice – always so well deployed in the “argument for the sake of heaven” – but equally in the arguments for a more tolerant and civilised world.

I was last in touch with Jonathan Sacks a couple of weeks ago and his chief of staff told me “ We have been rather overwhelmed by the outpouring of love and support for him.”

I am glad that, before his death, he was aware of this outpouring of genuine love and respect for this most accomplished and gifted of men. May he rest in peace.