The first evidence session in the Inquiry by the Joint Committee on Human Rights (JCHR) – into supply chains and modern slavery – will take place at 2.15 pm on 22 January 2025 in the UK Parliament – “Forced Labour in UK Supply Chains” – Oral evidence from Rahima Mahmut, UK Director at World Uyghur Congress, Michael Rudin, Executive Producer, BBC Eye Investigations at BBC, Professor Alexander Trautrims Associate Director at Rights Lab at the University of Nottingham.

Watch the proceedings live at : https://parliamentlive.tv/event/index/cc76fda6-914f-4d04-93cd-5a02d9421d17

The JCHR has also opened its call for evidence:

Call for Evidence https://committees.parliament.uk/call-for-evidence/3541/

Terms of Reference

Background

Forced labour is defined by the International Labour Organisation as “work or service which is exacted from any person under the threat of a penalty and for which the person has not offered himself or herself voluntarily.” In 2022, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in partnership with Walk Free and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) produced the Global Estimates of Modern Slavery report which found that 27.6 million people are subject to forced labour globally, including 3.3 million children.1

There is evidence that forced labour is present in UK international supply chains and that goods produced using forced labour are available on the market in the UK. As a result, British consumers could be enabling profit to be made from business practices which violate human rights. For example, testing commissioned by the BBC World Service, which included detailed trace element analysis, has indicated that processed tomatoes sold in British supermarkets labelled as being from Italy are highly likely to have been produced in China under forced labour conditions.2

At present, it seems that there is a potential disconnect between Government’s stated expectations that “no company in the UK … should have any forced labour whatsoever in its supply chain”,3 and the required legislative, regulatory and enforcement infrastructure to ensure that forced labour is identified and avoided.

Legal landscape

The UK has some international legal obligations concerning forced labour.

Article 4 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) prohibits slavery and forced labour and is incorporated in the UK’s own domestic legislation by the Human Rights Act 1998. However, a party to the ECHR – such as the UK – can only be held responsible for breaches of the ECHR which occur within its own jurisdiction.

The UK has also ratified a number of international agreements that prohibit the use of forced labour, including The Abolition of Forced Labour Convention 1957 developed by the International Labour Organisation (ILO), and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Article 8 of which prohibits slavery and compulsory labour. However, there are concerns about the scope and practical enforceability of such obligations in the UK.

The UK has been supportive of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), which provide a blueprint to address both business and state responsibilities to uphold human rights and set proposals for systems to handle complaints and provide access to remedies.4 Two National Action Plans have set out how the UNGPs will be implemented in the UK, however the only enforceable obligation that has been progressed in relation to upholding human rights in international supply chains is under the Modern Slavery Act 2015.5

Domestically, the UK’s Modern Slavery Act 2015 was considered to be world-leading legislation when passed in 2015, and generated a great deal of cross-party support. The Act established the office of the Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner, created harsher sentences to tackle modern slavery offences, and enhanced protection for victims.

Section 54 of the Modern Slavery Act 2015 created a requirement for companies with a turnover exceeding £36 million, and latterly public bodies, to issue an annual ‘Transparency in Supply Chains’ (TISC) statement setting out the steps taken to prevent modern slavery in their operations and supply chains. However, there is no set format for what should be included in the statement or established processes to verify information which companies receive from suppliers. Companies can meet their obligation simply by stating that they have taken no action (s.54(4)(b)). In October 2024, the UK Parliament’s Modern Slavery Act Committee examined the Act and concluded that UK’s response to modern slavery “has not kept up with the advances of other nations”.6

There is a patchwork of other domestic legislation which may be relevant to the detection and prevention of forced labour in supply chains based in the UK, including the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, the Foreign Prison-Made Goods Act 1897, and the Procurement Act 2023.

Terms of Reference

The inquiry will examine the UK’s current legal and voluntary framework in relation to forced labour in international supply chains, and whether it is effective in managing forced labour exposure risks in the UK market, or if changes are required. Supply chains based in the UK are covered by a different legal framework (as noted above) and hence will not form part of this inquiry.

It is understood that where individuals and groups are subjected to forced labour, accompanying risks of child exploitation and wider human rights abuses (such as prohibition of religious freedom) are likely to be heightened. While the inquiry will reflect evidence demonstrating these issues, these issues will not be a primary focus of this inquiry.

There is no need to respond to every question listed. Responders are encouraged to only answer the questions where they have evidence to share.

The deadline for submissions is the 13th February 2025. We would welcome evidence covering the following questions:

Legislative Framework

1. Are the obligations created by the Modern Slavery Act 2015 effective in preventing goods with international supply chains linked to forced labour being sold on the UK market? If not, what changes are needed to prevent goods linked to forced labour from being sold in the UK market?

2. How effective is other UK domestic legislation in preventing goods with international supply chains linked to forced labour entering the UK market? Are there any gaps? If so, what legislative improvements could be made?

3.Recent case law against the National Crime Agency suggests that British authorities and courts can have a role in addressing instances of forced labour in supply chains occurring outside the UK.7 What impact is this development likely to have on the way that companies consider the risk of forced labour and human rights in their supply chains, for example which suppliers they choose?

4.What international legal obligations does the UK have in relation to forced labour in supply chains? Is the UK’s current domestic approach compliant with those obligations?

5.What, if any, obligations does international law place on corporations when it comes to forced labour in their supply chains? Are these obligations effective?

6.Where should the responsibility lie for preventing products linked to forced labour from entering the British market? E.g. government, regulation, business, consumers, others?

Enforcement

7.In the UK, there are three public bodies which may potentially have a role in addressing goods linked to forced labour: the Anti-Slavery Commissioner, National Crime Agency, and Border Force.

a.What role does each body play in detecting and preventing goods produced using forced labour being available on the UK market?

b.Do these bodies have sufficient powers? If not, what other powers should they have?

c.How could these agencies work together most effectively?

Corporate activity

8.Are any sectors serving the UK market at particular risk of forced labour in their international supply chains?

9.Should companies of all sizes be required to manage the risk of forced labour in their supply chains? How could such an obligation be delivered in a manner which is proportionate to a company’s exposure to forced labour risks, number of employees, and annual turnover?

10.What could be done to improve corporations’ ability to identify forced labour risks in supply chains, and select suppliers that meet government’s expectations?

11.Where forced labour is a risk, what level of investigation/due diligence is it reasonable to expect from companies and public sector buyers before deciding whether to contract with suppliers?

12.How can a level playing field be achieved, where companies who operate supply chains free from forced labour are not at financial disadvantage?

13.How effective are the UN Guiding Principles at encouraging corporations’ consideration of the human rights impacts of business decisions? Please provide examples or evidence.

Consumer behaviour

14.If it becomes known that a company is using or at high risk of exposure to forced labour, what impact does this have on consumer attitudes or profits? Are consumers incentivised to avoid buying products that are likely to be linked to forced labour?

15.To what extent do existing transparency measures translate to accurate awareness of risk in customers?

Procurement

16.Does public procurement attract a higher risk of exposure to forced labour? If so, why is this the case?

17.How can the risk of exposure to forced labour be effectively managed in procurement?

International approaches

18.Are there particular elements of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act of 2021 in the USA that would be appropriate for consideration within a British Act? Please explain why you think such measures would be beneficial.

a.Are there any weaknesses or flaws in the US approach?

19.EU Member States have agreed two instruments to prevent the sale of goods linked to forced labour in the EU. Firstly the ‘Prohibiting products made with forced labour on the Union market’ and secondly the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). Are there elements of either the regulation or the directive that would be appropriate for consideration in the UK? Please explain why you think such measures would be beneficial.

a.Are there any weaknesses or flaws in the EU approach?

20. Are there any other nations with effective legislative frameworks to address goods linked to forced labour which may be useful for the Committee to consider?

===

Announcing the inquiry, Chair of the Joint Committee on Human Rights, Lord Alton said:

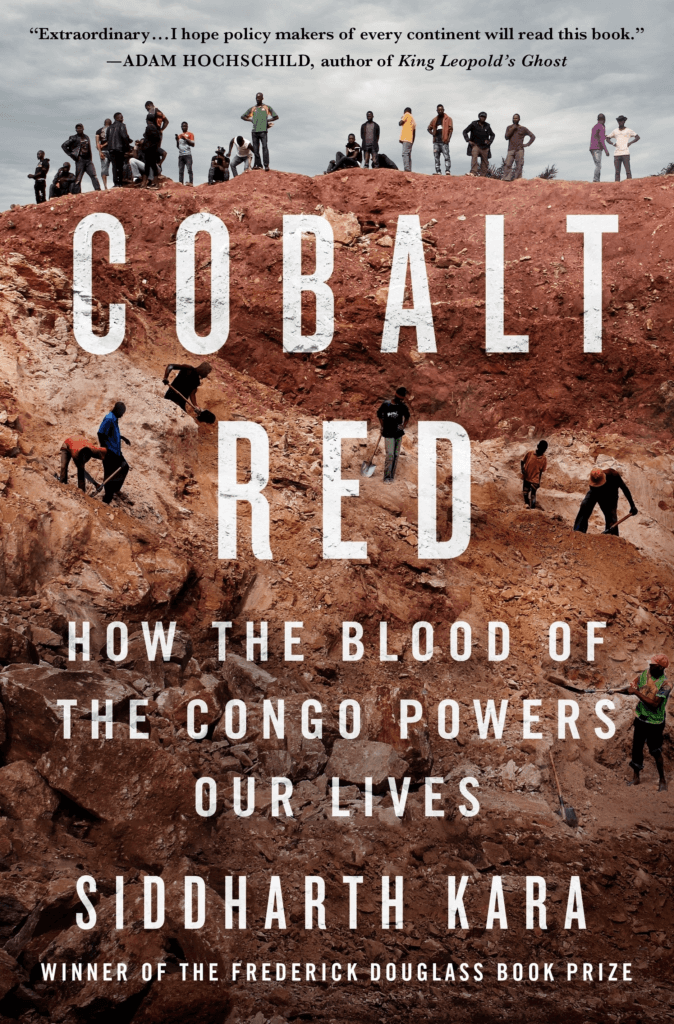

“The complexity and range of global supply chains have meant that consumers in the UK are undoubtedly buying goods made using forced labour. Over recent years we have seen reports of cases involving food, clothing and electronic goods. The extraction and production of raw materials can also see abuses, as well as in the production of finished goods themselves.

“It is vital that there is a strong framework of measures in place to prevent these goods entering the marketplace, that is why we have launched this inquiry. We want to see if current legislation is effective and whether lessons could be learnt from the approaches taken by other countries. We also want to explore how businesses can manage the risk of forced labour in their supply chains and better protect consumers.”