My Lords, in moving Amendment 43, I thank the noble Baroness, Lady Kennedy of The Shaws, the noble Lord, Lord Blencathra, and the right reverend Prelate the Bishop of St Albans for their support. I thank the noble Earl, Lord Russell, for indicating his support and that of his colleagues. I in turn am very happy to support his Amendment 100, which is grouped with Amendments 43 and 109.

I begin by thanking the Minister, the noble Lord, Lord Hunt of Kings Heath, for making good on his promise of a meeting to discuss this amendment, and for the involvement at that meeting of the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China. The noble Baroness, Lady Kennedy, is co-chair of IPAC with Sir Iain Duncan Smith, Member of Parliament. He, she and I are all sanctioned by the People’s Republic of China with four other parliamentarians. The noble Baroness, Lady Kennedy, regrets being unable to be here this evening.

During the meeting with the noble Lord, Lord Hunt, we discussed a number of questions I had raised at Second Reading. I would be extremely grateful if, when he comes to reply this evening—if he is in a position to do so—he could answer the question I put to him about the Foreign Prison-Made Goods Act 1897. In addition, can he say what assessment he and his officials have made of the implications of the Proceeds of Crime Act, which in the context of the Uighurs has been to the Court of Appeal on other issues, and for that matter of compatibility with the European Convention on Human Rights? I mention that as a member of the Joint Committee on Human Rights, which is about to be reconstituted tomorrow. I hope it will look at this question of human rights compatibility.

I should also mention the reports that have appeared on BBC World in the last couple of days. One of those reports concerns tomato purée being sold in the UK under the false label of being Italian, when it was actually made by slave labour in Xinjiang. Reports included details of Uighurs who were beaten and subjected to electric shocks for not meeting their targets. Last night, “Panorama” reported that other Uighur Muslims told BBC Eye—the World Service investigations unit, made possible by a grant from the FCDO—that if they failed to pick 450 kilograms a day, they would be strung up by chains from the ceiling and beaten until they fainted.

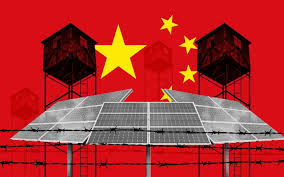

The BBC showed huge factories linked to the detention camps, with millions of square feet of space. It is easy to imagine solar panels being made in such places, which of course are not open to inspection. They are part of a vast collocated complex, which aims to undercut all competition and replace capacity, crucial to domestic and military needs in the United Kingdom, with a world dependent on an authoritarian state with hegemonic ambitions.

This amendment returns to the question that I raised at Second Reading and poses a simple question to the Committee: do we want a slavery-free green transition, or are we content to allow the laudable aims of the Government to be achieved through forced labour? Some noble Lords may disagree with the framing of the question, perhaps because they are fearful of overstatement. Unfortunately, as I have just described, the reality is that stark. My argument revolves around the following three predicates. First, China dominates much of the renewables supply chain—an issue that was raised earlier in our debates by the noble Lord, Lord Hamilton, and others. Secondly, forced labour is widely and credibly demonstrated to be present throughout the Chinese renewables supply chain. Thirdly, net-zero targets are unachievable without Chinese-made renewables. Therefore, the argument runs that 2030 cannot be achieved without slavery.

Let me unpack those predicates, beginning with China’s dominance. According to the International Energy Agency:

“Solar … is on course to account for two-thirds of this year’s increase in global renewable power capacity and further strong growth is expected in 2024”.

Indeed, the Minister referred to that in earlier exchanges. The International Energy Agency also said:

“China has invested over USD 50 billion in new PV supply capacity—ten times more than Europe—and created more than 300,000 manufacturing jobs across the solar PV value chain since 2011. Today, China’s share in all the manufacturing stages of solar panels (such as polysilicon, ingots, wafers, cells and modules) exceeds 80%. This is more than double China’s share of global PV demand. In addition, the country is home to the world’s 10 top suppliers of solar PV manufacturing equipment”.

This is a concerning picture.

Yet this should not come as any surprise. It is no secret that China has, for a long time, wished to develop strategic monopolies over the renewables sector, together with other areas of critical infrastructure. As I have argued here before—some might say rather tediously, and I apologise if that has been the case—we have allowed ourselves to become more and more dependent on the CCP regime as our own national resilience has simultaneously been emasculated. As recently as 2020, Chairman Xi Jinping gave a speech to the seventh session of the Communist Party’s finance and economy committee, in which he said that China will aim to form a counterattack and deterrence against other countries by fostering killer technologies and strengthening the global supply chain’s dependence on China.

The problem is broader than photovoltaics. The production of rare earths, which noble Lords will know is essential to the renewables supply chain, is again utterly dominated by China. As far back as the 1990s, Deng Xiaoping himself is reported to have said:

“The Middle East has oil, China has rare earths”.

A report by the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies says that

“China dominates the supply chain, accounting for 70% of global rare earth ore extraction and 90% of rare earth ore processing. Notably, China is the only large-scale producer of heavy rare earth ores. This dominance has been achieved through decades of state investment, export controls, cheap labour and low environmental standards”.

It is not just think tanks that are exercised about the degree of UK renewables market exposure. As James Basden, co-founder of Zenobē, said last year, China controls

“the supply chain all the way from the minerals through to assembly and distribution. That means both our power sector and automotive sector are very dependent on Chinese products”.

Suffice it to say, nobody disputes that China has a stranglehold on the renewables supply chain.

I turn to my second predicate: forced labour is unavoidable in the renewables supply chain. Forced labour is widely and credibly demonstrated to be present throughout the Chinese renewables supply chain. The problem is especially pronounced in the solar supply chain. According to Jenny Chase, the head of solar analysis at BloombergNEF:

“Nearly every silicon-based solar module—at least 95 percent of the market—is likely to have some Xinjiang silicon in it”.

Why would it be a problem for 95% of the market to have Xinjiang silicon? First, it is important to understand that polysilicon material is crucial—it is the single primary material needed to produce most solar panels.

Solar panels that do not use polysilicon enjoy a negligible share of the global solar-power market. Most crucially of all, according to a 2023 report by Crawford and Murphy, all manufacturers of this material in Xinjiang are tied to Uighur forced labour. The reason for this is that the entire process used to create metallurgical-grade silicon from mining to production is highly dependent on state-sponsored labour transfer programmes.

9.30pm

In 2021 Murphy and Elma published their landmark report, In Broad Daylight, which I cited at Second Reading, in which they set out the connection between labour transfer schemes in China and the solar industry. The report names a number of companies using labour transfer schemes. In the years following that, the problem has only got worse. The 2023 report, Over-exposed, says:

“None of the companies that were engaged in state-sponsored labour transfers in 2021 has announced any changes to its recruitment methods or shown any resistance to participation in the PRC Government’s programmes. Indeed, since that time, the PRC Government’s labour transfer programme has only increased in scale and the pressure on companies to absorb the workers the state deemed to be surplus remains high”.

The report names Canadian Solar, JA Solar, Jinko Solar, LONGi Solar, Maxeon Solar Technologies/SunPower, Meyer Burger Technology AG, Qcells, REC, Tongwei Solar, and Trina Solar. All companies were found to participate in state-imposed forced labour schemes. I note here that Canadian Solar was a major beneficiary in the recent solar development announcements made by the new Secretary of State. I note, too, that all the information used to compile these important reports comes from publicly available documents, many of which are Chinese government documents.

And what exactly are these labour transfer schemes that we would be signing up to and continuing to invest British taxpayers’ money in? The PRC has placed millions of citizens from the Uighur region into what it calls “surplus labour” and “labour transfer” programmes. Local governments and labour agencies are required to meet quotas for these programmes. As of September 2020, the Government of the Xinjiang Uigur autonomous region claims to have placed 2.6 million Uighurs and others in these state-sponsored programmes. In 2021, the Government reported as many as 3.2 million people transferred, and it appears that the programme is growing significantly.

Those who are conscripted into the programmes are compelled to transfer to work in farms and factories across the Uighur region, as well as into the interior of China. For those who do not come directly from the internment camps, the Government required that at least one person from every household in southern Xinjiang accept a state-mandated labour transfer to a factory or farm. And in December 2021, government directives required that all people who were able to work must be in some form of work. The PRC claims that these labour transfer programmes are part of a national campaign for poverty alleviation. However, the programmes involving Uighurs and other minority citizens operate differently from other poverty-alleviation programmes throughout China, because the constant threat of internment makes refusing the state-sponsored work placement impossible for individuals from the Uighur region.

Labour transfers are deployed in the Uighur region within an environment of unprecedented fear and coercion. Refusal to participate in any government programmes, such as labour transfers, for reasons perceived to be religious in any way is viewed as equivalent to aligning oneself with the three evils of separatism, terrorism, and religious extremism. Thus, anyone who refuses to work or attempts to walk away from their job risks internment or imprisonment. Therefore, the programmes are tantamount to the forcible transfer of populations, forced labour, human trafficking and enslavement by international definitions and protocols. I place on record here my gratitude to the Helena Kennedy Centre at Sheffield Hallam for its excellent brief on this point.

I turn to the third leg of the argument, namely that renewable targets are currently unachievable without slavery. On the face of it, the arguments seem to stack up worryingly. China controls the supply chain and state-imposed forced labour is present throughout it. How, then, will we meet our 2030 targets without slavery? The conundrum is that we appear to need Chinese solar to meet our climate targets, but Chinese solar is badly tainted, as I have described, with modern slavery.

This is not just about modern slavery and Uighur genocide: the CCP regime is the world’s biggest polluter, and it uses the Uighur region as its national hub for oil, gas and coal, fuelling their factories with cheap coal. So, the solar panels of Xinjiang are not only made by slave labour but have a higher carbon footprint than those manufactured elsewhere in the world.

So, what do we do? Despite this deliberately created monopoly, built on the broken backs of slaves, we do not have to become complicit. Other countries are facing the same dilemma and are acting to address it. German solar companies are calling on the German Government to support the domestic solar industry and help resurrect it. The US Government have included a ban on imports from a silicone producer in Xinjiang. Canada has banned the import of solar panels from specific Chinese companies, while Australia has called for more local renewable energy production and manufacturing and a “certificate of origin” scheme to counter concerns about slave labour.

What is clear is that if democratic nations like ours are to achieve decarbonisation, this will need a mix of approaches: developing alternatives not dependent on polysilicon, rebuilding domestic solar supply chains, focusing procurement on companies that have shifted supply chains out of Xinjiang, and developing better tools for reliable sourcing.

All this hinges on our Government insisting that they will not be purchasing solar panels from companies that use slave labour, prioritising instead ethical sourcing and labour practices and recognising that such firm action is the way to create demand for responsible production.

I hope that I have not exhausted the Committee, but these are crucial questions, and they involve much of the £8 billion that we are setting aside for these programmes. Rebuilding our national resilience and reducing our dependency on authoritarian states who threaten our freedoms should be in the DNA of every policy the Government promulgate. I beg to move.

My Lords, my Amendment 100 seeks to insert a new clause after Clause 7 that would require Great British Energy to verify its supply chain in respect of unethical practices and to attempt to engage in ethical supply chain practices only. I will also speak in favour of the principles contained in Amendments 43 and 109 in this group, moved by the noble Lord, Lord Alton, and supported by others.

To be clear, I believe in people and planet, and we should not have to choose one or the other. The two are intertwined and co-dependent. Our goal of reaching net zero must not come at the expense of supporting repressive regimes which do not support the human rights of their own citizens, or on the back of slave labour.

The truth is that it is certain that a proportion of the supplies and materials used in this country as part of our efforts to decarbonise have unknown ethical origins or, if we look more closely, are probably produced in regimes with modern slavery practices.

Polysilicon manufacturers in China account for some 45% of the world’s supply, and some 80% of the world’s solar panel manufacturing. As the noble Lord, Lord Alton, alluded to, Sheffield Hallam University has linked forced labour in China’s labour transfer programme directly to the global supply chain of solar panels. Some 11 companies were identified as engaging in forced labour transfer, including all four of China’s largest polysilicon producers. Some 2.7 million Uighurs are subject to state detention and coerced work programmes.

The combination of unethical practices, cheap labour and deliberate foreign policies means that China controls much of the world’s rare earth materials and manufacturing that is necessary to produce solar panels. China built more renewable technology than the rest of the world combined last year. But China is still opening and highly dependent on coal mines. It is time for China itself to choose which side of the green revolution it is on.

It is not in our national interest to continue with such foreign power dependence in order to secure our net-zero goals. What actions are the Government considering or planning to undertake, along with our allies and partners, to verify supply chains and build our own manufacturing capacity, particularly for solar panels, so that we are not dependent on foreign countries for the materials we need to decarbonise, and so that we can be certain that the products we use are not the result of human suffering? I hope the Prime Minister raised these important issues in his recent meeting with the Chinese President.

My amendment would place a duty on GB Energy to verify and engage in ethical supply chain practices. This is not the end of the journey, but it is a start. Of course, these problems extend way beyond GB Energy and these measures should be implemented nationally.

Amendment 43 says that no financial assistance must be provided

“if there exists credible evidence of modern slavery in the energy supply chain”.

Amendment 109 calls for a warning to be placed on any products sourced from China that are used by GB Energy. Although I support the spirit and intention of both these amendments, my worry is that the Government will not be able to support them and that they will fail.

My fear is that if Amendment 43 passed it would put GB Energy at an unfair disadvantage in relation to other competitors in the industry operating in the UK. For this reason, the Government will most likely reject it. On Amendment 109, I expect that the implication of labelling these products might simply be to prevent their purchase by GB Energy, while other competitors in place in the UK marketplace without this labelling requirement would be able to continue their supply. Again, my worry is that this would do more to put GB Energy at a disadvantage versus its competitors operating in this country. The Government will probably reject the amendment on those grounds.

My hope is that my amendment or a newly tabled one on Report might help us to find a way forward together on this important issue, which we all need to make progress on. To be clear, this issue goes well beyond GB Energy, and the real long-term solutions to it sit with the verification of supply chains, strong and determined diplomacy, the creation of and investment in solar panel manufacturing on our own or along with our allies, or the research and development of new forms of manufacturing processes for these technologies. These are essential issues, but I suspect we will need to engage constructively together to find a way forward prior to Report, and that the solution, ultimately, goes beyond the scope of the Bill and GB Energy.

My Lords, I thank the noble Lord, Lord Alton of Liverpool, and the noble Earl, Lord Russell, for their amendments. We all agree that modern slavery is one of the great scourges of our time. It is estimated that tens of millions of people are trapped in forced labour worldwide, many of them in sectors tied to energy production and manufacturing. Indeed, as the noble Lord and the noble Earl pointed out very eloquently, renewable energy technologies such as solar panels rely on materials such as polysilicon, much of which is sourced from regions where reports of forced labour and human rights abuses are widespread.

These amendments seek to ensure that GBE operates with integrity and accountability in its supply chain practices. Each amendment addresses a crucial aspect of ethical responsibility, and together they would bind the Government to ensure clean energy does not come at the expense of human rights, ethical labour practices or transparency. I encourage the Government to look at this matter carefully. Can the Minister explain what measures will be put in place to ensure that there is oversight of Great British Energy’s supply chains? If Great British Energy is to represent the values of this nation, there is a strong case for tougher measures to prevent public funds being spent in a way that supports or sustains supply chains that exploit human beings.

On Amendment 109, while I recognise the sensitivity and complexity of this issue, it is crucial that we approach it with transparency and courage. Consumers and stakeholders have a right to know the origins of the products they use and the conditions under which they are made. I hope the Minister will listen carefully to the arguments made on this matter; we on these Benches will be very interested to hear his reply.

As a publicly backed entity, Great British Energy has an opportunity to set an example and be a model to other countries. I am sure the Government agree there are opportunities here and we look forward to hearing their response.

My Lords, I thank the noble Lord, Lord Alton, for his expert introduction to the amendment. I also thank the noble Earl, Lord Russell, for his wise comments. I say to the noble Lord, Lord Offord, that we are, of course listening very carefully to this important debate, and I have no doubt whatever about the gravity of the issue. The amendments seek to highlight the importance of ensuring that our supply chains are protected from forced labour, and I wholeheartedly support this.

9.45pm

As a Government, we are committed to tackling the issue of forced labour in supply chains, including the mining of polysilicon used in the manufacture of solar panels. I refer to guidance issued by the last Government, published in July 2023, which highlighted the risk of doing business in Xinjiang. It urged businesses with supply chains in this province to exercise caution as they may

“face particular reputational, economic and legal risks, due to extensive and credible evidence of forced labour programmes, targeting Uighur and other ethnic minorities.”

There is, of course, also the enforcement action which can be taken against those who fail to report, as required under Section 54 of the Modern Slavery Act.

Great British Energy will be expected to respect human rights under the Human Rights Act. It will be subject to the existing provisions in legislation on forced labour supply chains under the Modern Slavery Act 2015, and under the Procurement Act 2023 when this is fully in force in February 2025. The noble Lord, Lord Alton, asked about another piece of legislation. We are still working on it, and I will definitely come back to him with a response.

The Procurement Act, which the noble Lord, Lord Alton, and I happily debated, will strengthen public sector contracting authorities to exclude suppliers and disregard their bids where there is sufficient evidence of modern slavery, which extends to supply chains across all countries, including China. This will apply whether or not there has been a conviction. GBE will also be committed to building supply chain activity in the UK to accelerate the deployment of key UK energy projects. Under the Procurement Act, where Great British Energy is a contracting authority, it will be able to disregard tenders where it is aware of forced labour or modern slavery existing in the supply chain. In addition, Section 54 of the Modern Slavery Act 2015 requires companies with a turnover of £36 million or more to publish an annual modern slavery statement setting out steps which they have taken to prevent modern slavery in both their operations and supply chains.

There are, in addition, other legal mechanisms. The UK supports voluntary due diligence approaches taken by UK businesses to respect human rights and the environment across their operations and supply relationships, in line with the UN guiding principles on business and human rights and the OECD guidelines on multinational enterprises. In summary, the Government expect UK businesses, including Great British Energy, to do everything in their power to remove any instances of forced labour from their supply chains, and they should not approve the use of products from companies that may be linked to forced labour.

I turn to the issue raised by the noble Earl, Lord Russell. Clearly, forced labour in supply chains is wide ranging in nature. The Bill, with its relatively narrow focus on setting up an operationally independent company and on making the minimum necessary provision for that purpose, is not the appropriate vehicle for tackling this issue. However, I want to assure the noble Lord, Lord Alton, that we are committed to tackling forced labour in supply chains. We have recently announced the relaunch of the solar task force, which has previously focused on identifying and taking forward the actions needed to develop resilient, sustainable and diverse supply chains free from forced labour. This is obviously very important, given our ambitious target to increase our solar capacity by 2030, to which the noble Lord, Lord Alton, referred.

The UK’s main solar industry trade association is leading the industry’s response by developing and piloting the Solar Stewardship Initiative to further develop a responsible, transparent and sustainable solar value chain. The UK Government supported this effort by co-sponsoring the development and publication of Action Sustainability’s Addressing Modern Slavery and Labour Exploitation in Solar PV Supply Chains Procurement Guidance. This provides further tools to the industry to ensure the responsible sourcing of solar panels.

In conclusion, we do not think that the Bill is the right vehicle for this but, through the reconvened solar task force, we assure the House that we are working widely across Whitehall and with industry stakeholders to take forward the actions needed to develop supply chains that are resilient, sustainable, innovative and free from forced labour. We will set out these actions in the solar road map, which is expected to be published in spring 2025.

In the meantime, I am very happy to engage further with the noble Lord, Lord Alton, and to feed his views into the task force. I hope to make progress.

I am indebted to the Minister—I will come back to that in a moment—and I thank the noble Lord, Lord Offord, and the noble Earl, Lord Russell, for their contributions to this debate. I was heartened by the in-principle support that they gave for what these amendments are seeking to achieve. I pick up a point from the noble Lord, Lord Offord, about the consumer having the right to know the origins of products. I feel very strongly about that and there is much more that we can do about it in due course.

I am a free trader, but I am always struck that it was Richard Cobden who drew lines in the sand. He said no to free trade when it came to human beings in the slave trade and no when it came to the opium trade. A three-day debate in the House of Commons led to the overturning of that trade, which to this day has some relevance in the context of China. Consumers can play their part in those activities and campaigns, because they can say no by voting with their feet, but they have to know what the origins are. That means that we have to do more to detect them. The noble Lord, Lord Rooker, often says that we can look at the cotton that comes out of places such as Xinjiang to detect its DNA, or at silicon or other raw materials.

And we should go right back in those supply chains. I made the point at Second Reading that 25,000 children are believed to work in cobalt and lithium mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. So these are things that matter a great deal to a lot of people in different places, and we can do more about them.

I know the Minister is no stranger to these issues. He was right to mention the Procurement Act and the joint efforts we made successfully to raise amendments to that. As he knows, I was involved in the modern slavery legislation in 2015, and I always give great credit to noble Baroness, Lady May, as she now is, who was then the Home Secretary, in bringing forward what was bipartisan and bicameral legislation.

Picking up a point that others have made this evening, the noble Lord, Lord Cryer—whose father I had the privilege of serving with in the other place—said earlier today that what he likes about this House is the willingness to try to find solutions, being less confrontational and working with one another to find ways forward. I hope we will try to do that.

It is difficult to square the circle. There are contradictions and inconsistencies here; it feels almost like Jekyll and Hyde in some respects. We have the Business Secretary, Jonathan Reynolds, saying:

“I give … an absolute assurance that I would expect and demand there to be no modern slavery in any part of a supply chain that affects products or goods sold in the UK … I promise … that, where there are specific allegations, I will look at those to ensure that”

this happens.

“It is an area where we have existing legislation, and indeed we would go further if that was required”.—[Official Report, Commons, 5/9/24; cols. 418-19.]

So I welcome what the Government have been saying, but the reality, when you start to look at supply chains and where these products are made, does not sit very comfortably with those promises.

On the basis of what has been said evening, I beg leave to withdraw Amendment 43, and I hope we can find scope to come forward with something on which we can agree at Report stage.

Amendment 43 withdrawn.

Amendments 44 and 45 not moved.

Clause 4 agreed.

House resumed.