Lord Alton of Liverpool

(2 speeches)

For more information about the: Otto Habsburg Foundation.

Speech for Opening of the conference

It is a singular honour to have been invited by Gergely Prohle the Director of the Otto Von Habsburg Foundation to open your Conference today. Looking at previous conferences I realise that I am standing on the shoulders of giants.

In words that can be measured against the growth of contemporary totalitarianism, I once said that Otto von Hapsburg “would no doubt have concurred that a monarchy which combines wisdom with benevolence and service for the common good is preferable to the tyrannies symbolised by dictatorship and totalitarianism in so much of our world today.”

The Austrian Otto, as the Americans called him, loathed totalitarianism, and embraced the age-old Habsburg principle of “live and let live” among the many peoples, minorities, ethnicities, languages, and cultures which characterised the Austro-Hungarian Empire – the beauty of diversity and difference.

In the twentieth century the most resolute opponent of totalitarianism was Winston Churchill, with whom Otto von Habsburg enjoyed a close friendship, and this Conference is specifically being held to mark the 150th anniversary of Churchill’s birth.

Their personal and political outlook was not so vastly different, and it is not difficult to see why their relationship prospered.

In their long lives, both saw the fall of empires and the rise of autocrats; loathing totalitarian ideology and the regimes it spawned.

Both used their voices to sound the alarm.

Unheeded, and in the aftermath of cataclysmic war, they used their formidable experience and energy to rebuild political and international institutions and Europe itself.

But there were differences.

Unlike Habsburg – with a Doctorate – and who was a scholar – Churchill was a brilliant wordsmith but had not attended university and was indifferent to philosophy.

Nor did Churchill share Habsburg’s deep religious faith although he seems to have believed in God and in Providence.

But both men held that politics and religion, when informing one another, could strengthen civilization and unite, comfort and, at its best, inspire the people.

Habsburg emphasised the role of religion with words which Churchill would have concurred. At the 1952 International Eucharistic Congress, he said: “In reality the Christian Empire is more the spirit of solidarity, the Pax Christi thought, the practical implementation of gospel principles…”

Churchill is sometimes described as a “Christian Humanist” –not believing in Christ’s divinity but describing Him as the most outstanding moral teacher the world had ever produced. Churchill is reported as saying to Field Marshall Montgomery” the Sermon on the Mount was the last word in ethics.”

Churchill famously remarked “I could hardly be called a pillar of the Church. I am more in the nature of a buttress, for I support it from the outside.”

In March 1949, speaking in the United States at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Churchill summed up his beliefs in these terms:

“I speak not only to those who enjoy the blessings and consolation of revealed religion but also to those who face the mysteries of human destiny alone. The flame of Christian ethics is still our highest guide. To guard and cherish it is our first interest, both spiritually and materially. The fulfilment of spiritual duty in our daily life is vital to our survival. Only by bringing it into perfect application can we hope to solve for ourselves the problems of this world and not of this world alone”

Both Habsburg and Churchill were practical men who believed that the application of the beliefs which guided them was the most important thing: guiding them through the gathering storm and dangerous headwinds.

In 1900 Churchill was first been elected, as a Liberal, to the House of Commons.

After the First World War he held office as a Conservative but throughout the 1930s became an increasingly isolated figure because of his trenchant opposition to appeasement.

Habsburg having denounced Nazism as “the most ruthless subjugation of the Austrian people…” had also experienced isolation and rejection – even denied citizenship and orders issued that, if caught, Hapsburg was to be executed immediately.

Such hatred was no doubt intensified by reports that Hapsburg was helping thousands of Austrians, including thousands of Austrian Jews, flee the country.

Churchill was also in their sights.

In 1938 Hitler attacked Churchill as “a warmonger” which led to a withering response from Churchill in the House of Commons expressing surprise that “the head of a great State should set himself to attack British members of Parliament who hold no official position and who are not even the leaders of parties” and which he believed would only enhance his own reputation.

Tragically for Europe the second war of the century proved even more deadly than the first, leaving sixty million dead, in 1940 around 3% of the global population.

By 1946, in the rubble of Europe’s cities and amidst the vast oceans of refugees, Churchill reflected on the post-World War One Settlement and mused that “If the Allies at the peace table at Versailles had allowed a Hohenzollern, a Wittelsbach and a Habsburg to return to their thrones, there would have been no Hitler”.

He wanted a settlement that did not repeat the worst of the mistakes of 1919.

Among the ideas which Churchill supported was Habsburg’s idea of creating a “Danube Federation.” It was vetoed by the father of today’s tyrants, Joseph Stalin.

Churchill was clear that a further cycle of revenge in Europe had to be replaced by a “European family” with the hallmarks of mercy, justice, and freedom.

He was one of the first to call for European integration, the creation of a United States of Europe, a European army, the reduction of economic frontiers, the creation of a single currency, and a tariff union.

In 1949 he argued for the establishment of the Council of Europe and, in 1959, a European Court of Human Rights

Churchill insisted that “in the centre of our movement stands the idea of a Charter of Human Rights, guarded by freedom and sustained by law.” He was in no doubt that new threats would emerge to replace those which had been vanquished: “The dangers threatening us are great but great too is our strength, and there is no reason why we should not succeed in … establishing the structure of this united Europe whose moral concepts will be able to win the respect and recognition of mankind.”

“In all this urgent work” he explained, “France and Germany must take the lead together” while Britain and its Commonwealth, the US and the Soviet Union should be its friend and “must champion its right to live.”

This ‘one step removed’ place of Britain is still contested in the UK by Remainers and Brexiteers alike and has an echo in his remark, penned in 1930, in a newspaper article, that “We are with Europe, but not of it”.

Perhaps now is the ideal time to reconcile Churchill’s idea of nation states working together in Europe with Habsburg’s specific call for Christian renewal. If those parallel ideas could be woven into a political programme it might better speak to the challenges of today and simultaneously provide a way for Britain to play its proper part in the life of Europe.

That said, Churchill’s internationalism was never just about Europe. How could it be? He was the ultimate Atlanticist and would have loathed contemporary trends in the US towards isolationism.

In his famous 1946 “Iron Curtain” speech at Fulton, Missouri, and in the presence of President Harry Truman, Churchill warned of the dangers of disengagement and isolation.

He said that the new United Nations must not go the same way as the League of Nations: “not a sham…a force for action and not merely a frothing of words.” He feared it would all too easily become a cockpit in a Tower of Babel.

In an idea that speaks to us today from the ruins of cities in Ukraine, the Middle East, Sudan and the Horn of Africa – and to the 23 million free people of Taiwan – Churchill identified the threats from fascist, communist and police states and argued that to keep the peace the new UN should be able to deploy “an international armed force.”

Churchill knew that Europe could not do this alone.

In his “Iron Curtain” speech, he emphasized the necessity of democracies standing together and the duty which comes with economic and political power: “It is a solemn moment for the American Democracy. For with primacy in power is also joined an awe-inspiring accountability to the future … When the designs of wicked men, or the aggressive urge of mighty States, dissolve over large areas, the frame of civilized society, humble folk are confronted with difficulties with which they cannot cope. For them all is distorted, all is broken, even ground to pulp.”

As in speaking to Europe he forcefully told his American audience that society must be built on the basis of the rule of law and strong international alliances, citing the American Declaration of Independence and Magna Carta, denouncing states “ruled by dictators, or by compact oligarchies operating through a privileged party and police state.”

Here too were the birth pangs of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation with its defining Article 5 providing mutual support – with an attack on one, being an attack on all.

But so many of the hopes of a more united world were dashed by the closing of that curtain of iron.

While Churchill was undoubtedly the greatest of British Prime Ministers, we would not call him great – or even remember him – if the clock had stopped ticking in 1939.

His disastrous decision in 1915 over the invasion of Turkey at Gallipoli, his advocacy of the use of poison gas, his treatment of strikers, support for eugenics, the mishandling of the economy during the inter-war years, and his defenestration of Mahatma Gandhi, were among his worst misjudgements and mistakes. He suffered from depression, mood swings – what he called the Black Dog followed by periods of frantic activity leading Franklin D. Roosevelt to say of him: “He has a thousand ideas a day, four of which are good.”

But Hitler and the struggle against Nazism changed all that.

On the same day that Hitler unleased the Blitzkrieg, Churchill was appointed Prime Minister. Some saw it as truly Providential – with the failures and errors that had gone before simply being a preparation for the moment which had come.

I was a boy when, in 1965, Churchill died. My first visit to Westminster was to walk in respect, with millions of others, past his coffin, laid in state in Westminster Hall.

Following Churchill’s death Otto von Habsburg was elected to the new European Parliament serving between 1979 and 1999, becoming its senior member.

A member of the Christian Social Union of Bavaria (CSU) Hapsburg shared the political beliefs of the great European Christian Democrats – Konrad Adenauer, Alcide de Gaspari, and Robert Schuman and what became the European People’s Party (EPP).

Churchill believed in social reform, including education and prison reform. He never wavered in his passionate belief in individual liberty and free markets and was always hostile to overweening state socialism. Churchill and Habsburg both had strong belief in the importance of family and family life

Hapsburg shared Schuman’s insistence on recognising Europe’s Christian tap roots:

“Democracy owes its existence to Christianity. It was born the day that man was called to realise in this temporary life, the dignity of each human person, in his individual liberty in the respect of the rights of each and by the practice of brotherly love to all. Never before Christ were such ideas formulated. Democracy is therefore bound to Christianity, doctrinally and chronologically. It took shape with it by stages and with periods of stumbling, sometimes at the price of errors and falling back into barbarism.”

This political and religious belief in human dignity and individual liberty was rooted in the personalism of the great but sadly neglected philosopher Jacques Maritain.

Churchill was suspicious of philosophers.

The question for him was always about what actions had to be taken to protect free societies from the barbarians.

Throughout World War Two he famously employed red stickers of his own invention labelled: “Action This Day.”

He fixed them to memos and documents insisting that immediate action be taken.

Once the final battles had been fought, both Churchill and Hapsburg clearly saw the threat that the Soviet Union’s quest for world dominance then posed – no different from today’s deadly quartet of Putin’s Russia. Xi’s China, Kim’s North Korea and Khamenei’s Iran.

Whether we have the same zeal that in the 1940s led to demands for a just world order, leading to a Convention Against Genocide, a Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Marshall Aid Programme, the Bretton Woods System aiming to provide an international economic framework, European institutions, and a frenzy of activity on so any more fronts, is another matter.

Seth Jones in Foreign Affairs recently wrote that China has roughly 230 times the shipbuilding capacity of the US – a single one of its shipyards can produce more ships than every American shipyard combined.

In the past three years, the country has more than doubled its stockpiles of nuclear warheads, ballistic missiles and cruise missiles; produced more than 400 modern fighter aircraft; and increased its satellite launches by 50%.

US. Admiral John Aquilino, the former commander of the US Indo-Pacific Command, says the CCP’s military expansion is “the most extensive and rapid build up since World War Two”. We sometimes seem oblivious to the scale of the danger and the threat.

Today, in a world where 120 million people are displaced, where conflict and war are raging, where a new breed of dictators and autocrats are forging new deadly alliances, where democracy is faltering in the face of angry populism, where millions are persecuted because of their religion or belief, we need the same zeal and, action on this day.

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill was born, 150 years ago on November 30, 1874, in Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire.

How fitting it is that we are here to celebrate the birth of a great statesman whose life and times can teach us so much today.

After Dinner Speech at the Otto von Habsburg Foundation Gala Dinner To Celebrate The 150th Anniversary of The Birth of Winston Churchill

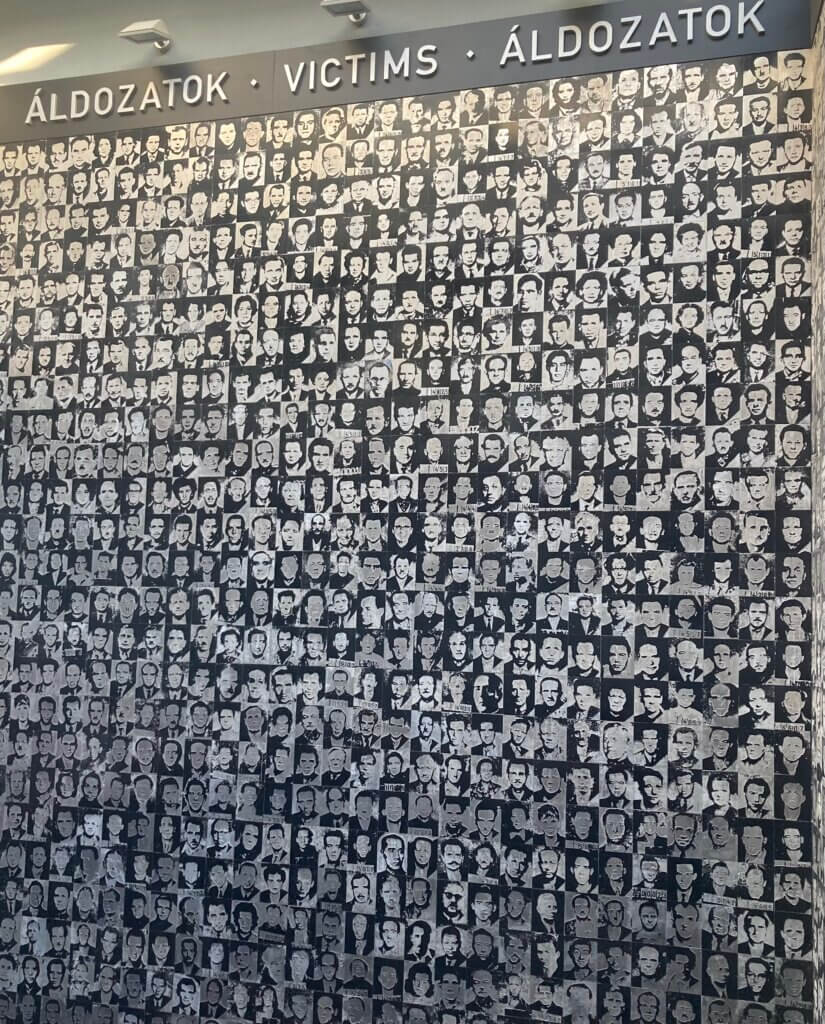

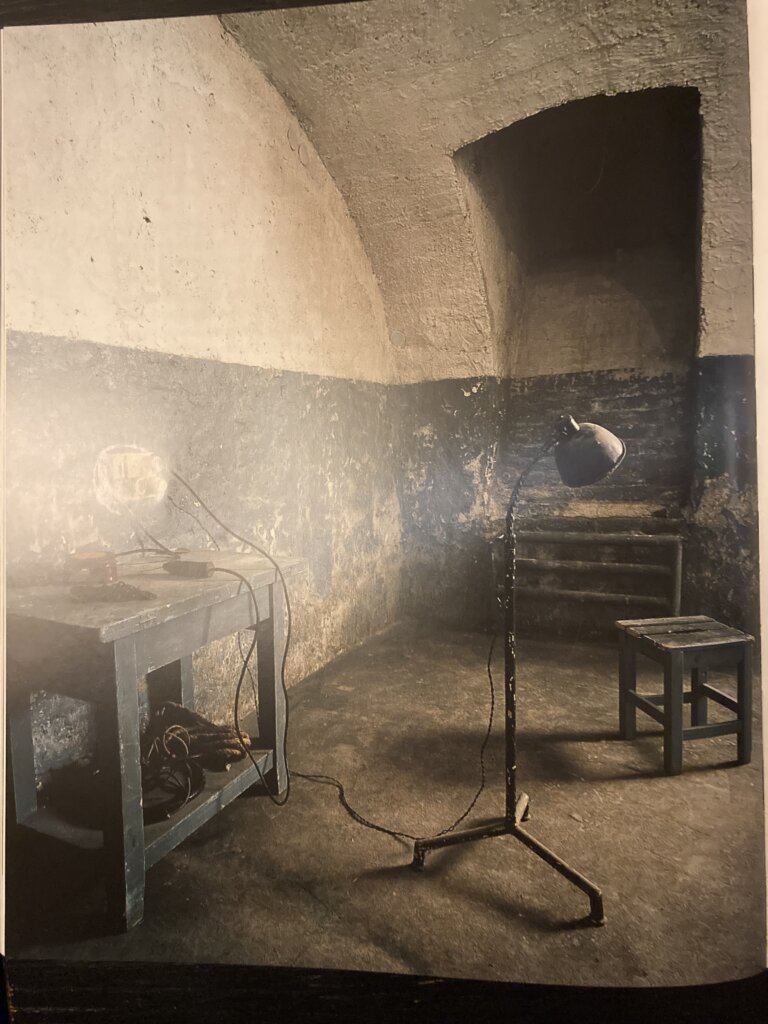

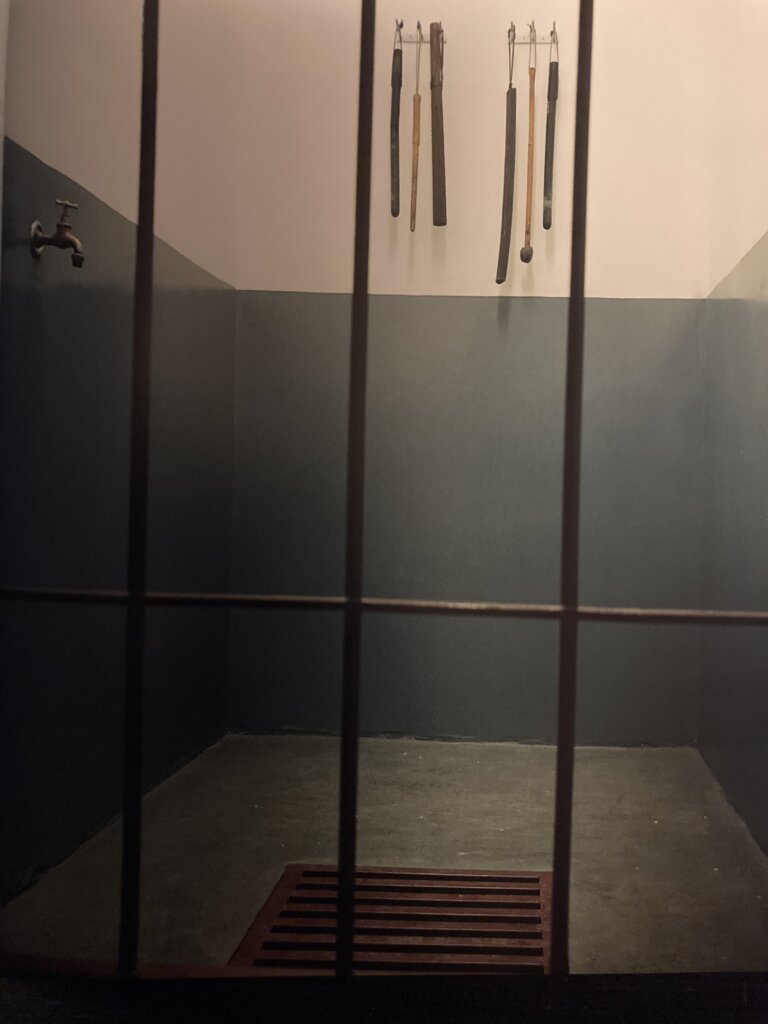

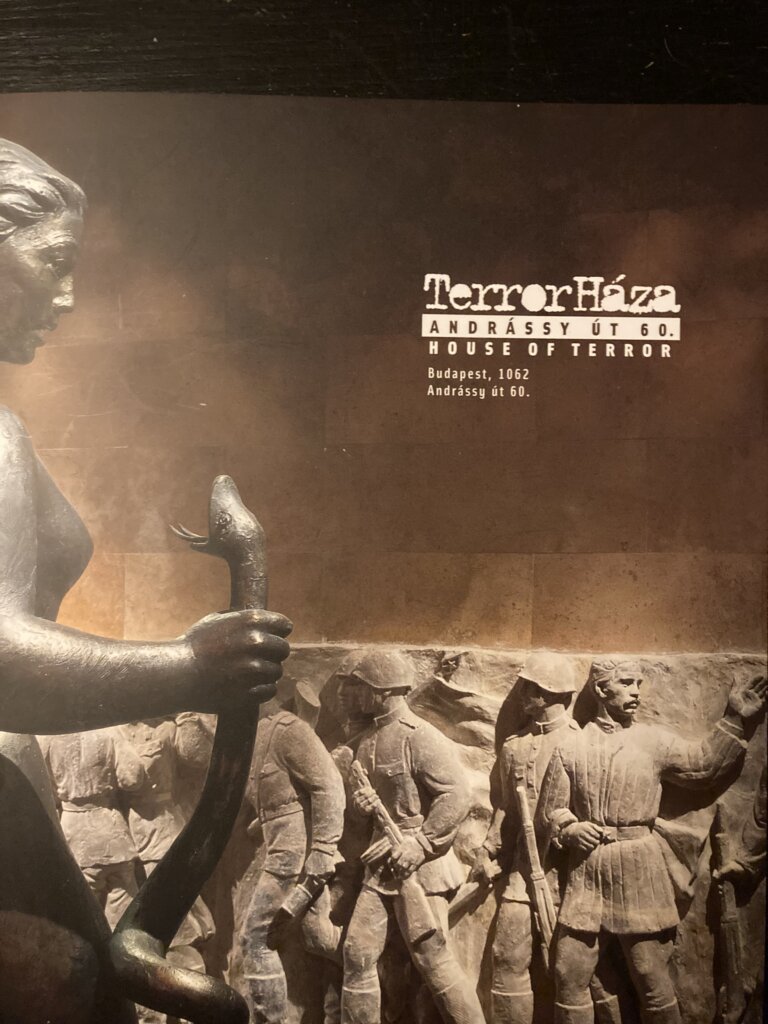

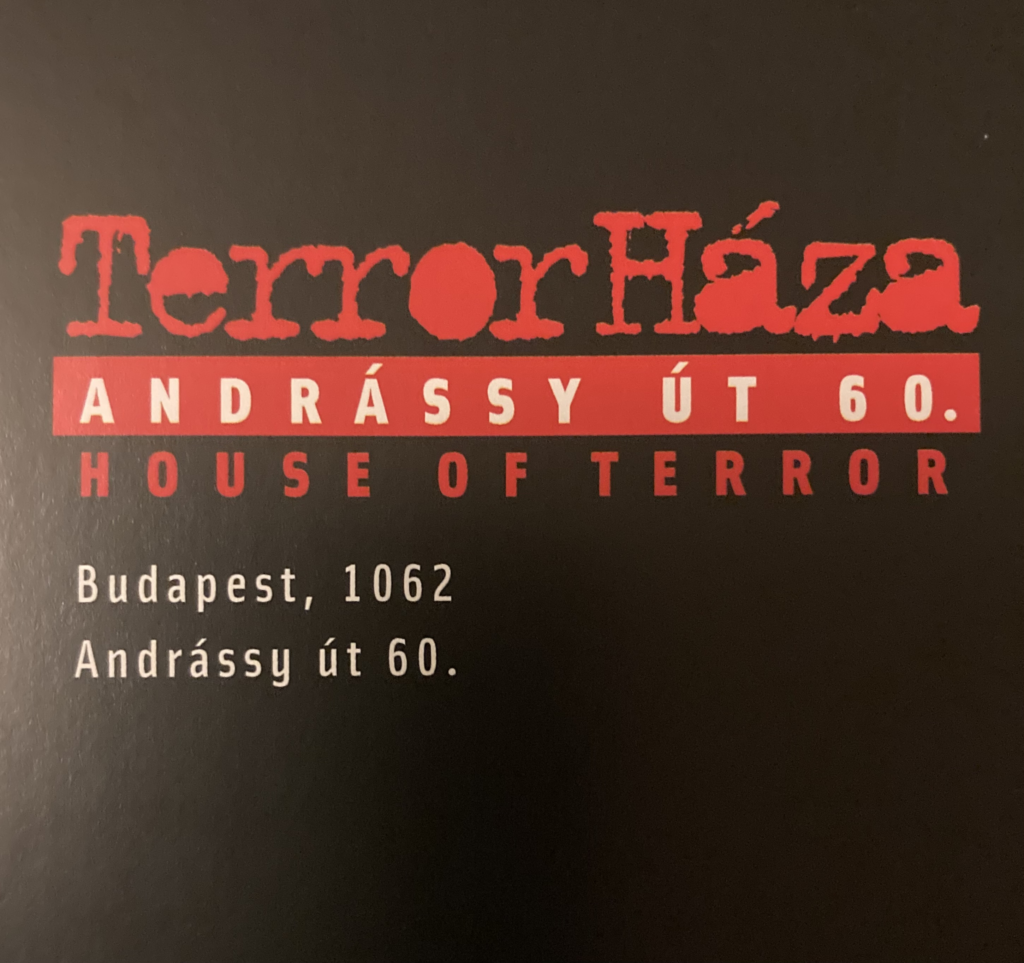

It’s a real privilege to be following in the footsteps of some remarkable speaker who have addressed preceding Gala dinners. i should begin by thanking the organisers who have staged such an excellent conference – and especially thank them for arranging my visit today to the House of Terrors in Budapest which so vividly recalls the torments of fascist and communist dictatorship.

And it is no small challenge to offer a few words about two of the most outstanding and significant human beings of the twentieth century: Winston Churchill, in this 150th year of his birth, and Otto von Habsburg, whom Martyn Rady’s described as “the best emperor the Habsburgs never had “.

Some of you had the misfortune to hear me at the opening of your Conference yesterday.

Forgive me if I repeat any of my remarks – but, if I do, bear in mind what once happened to Winston Churchill.

In the halcyon days before word processors, iPads, tablets, texts, emails and social media, you may recall that pieces of carbon paper were placed in the typewriter to make two copies of each page.

However, on one notable occasion, Churchill’s typist mistakenly stapled a page of the carbon copied speech into the finished text and he found himself saying the same words all over again.

Hardly pausing for breath, he told his audience: “You may wonder why I am repeating myself; it is because it is so important….”

Well, he had no shortage of important things to say, and happily, a team of typists preserved for us his remarkable speeches – everything from ‘Blood, toil, tears and sweat’ to ‘We Shall Fight on the Beaches’ and ‘This was their Finest Hour’.

Churchill didn’t, however, have a very high opinion of some of the speeches given by his opponents. Evaluating a speech by a fellow Member of Parliament, Churchill once said: “He spoke without a note and almost without a point.”

Another time he wryly observed: “Too often the strong, silent man is silent because he has nothing to say.”

In Parliament he is famous for having used his gift with words to eviscerate political opponents; once describing the Labour leader, Ramsey MacDonald as the man with “the gift of compressing the largest number of words into the smallest amount of thought.”

And his withering humour could be extended to his Conservative colleagues too.

When asked what should be done if his bête noire, Stanley Baldwin, three-time Prime Minister, should die in office, Churchill quickly responded, “Embalm, bury, and cremate. Take no chances!”

Churchill’s directness had its consequences – not always endearing him to his colleagues. In 1938 he was booed in the House of Commons:

Following Nazi Germany’s annexation of portions of Czechoslovakia and the creation of Sudetenland he said of Neville Chamberlain’s Munich Pact with Hitler: “You were given the choice between war and dishonour; you chose dishonour and will have war.”

Circumstances ultimately provided Churchill with the opportunity to put his extraordinary gifts of leadership at the service of his country. He never doubted he had been made for greatness and I am sure he recognised in Otto von Habsburg many of those same attributes and characteristics.

In these dispiriting and troubled times, we need the inspiration and example of two men who knew that without security and stability there could be no economic prosperity or progress.

Both men knew that politics and politicians had to speak to the anxieties of the times – not to do so would open the door to populism, autocrats, and extremism.

Both gravitated to the politics of the centre

Both men had a vision of the dangers posed by dictatorship to the world’s democracies.

Both identified the curse of Nazism.

Both loathed antisemitism and spoke up for the persecuted Jews.

Both saw in Stalin a continuation of the barbarism of Hitler.

Both were passionate in their belief in democracy, the rule of law and the upholding of human rights and human dignity.

Both were committed to a pan Europeanism – which meant the whole of Europe – represented by the empty chair for the missing States in the European Parliament and more recently poignantly left out for the now deceased Alexei Navalny – and, while Churchill coined the phrase “the iron curtain”, both men knew it wouldn’t last for ever.

Throughout Otto von Habsburg’s time in the European Parliament he was an ardent opponent of the Communist Soviet Union and yearned for the fall of the Berlin Wall.

But – using a gift he shared with Churchill – he prophetically saw the coming dangers too

In 2002, in a newspaper interview and in speeches in 2003 and 2005, he warned that Vladimir Putin was an “international threat” that he was “cruel and oppressive” and a “stone cold technocrat”.

He warned Europe that “a real international danger continues to exist.”

Right up until his death he warned against revisionist “national Bolshevism”, the danger of new Russian “colonial wars in Europe” and he drew comparisons between Putin and Hitler.

Despite claims to the contrary, history is never over and the battle for freedom is perennial.

As Ronald Reagan – born a year before Otto von Habsburg – famously observed freedom is “never more than one generation away from extinction.”

Freedom comes with a high price tag: freedom is never free.

In confronting the deadly quartet –four apocalyptic dictators- Putin, Xi, Kim and Khomeini – and their many imitators – we have failed to understand what Otto von Habsburg saw so clearly.

Recall his refusal to meet Hitler- and the price the Nazis put on his head.

What would he or Churchill had to say about today’s kowtowing and grandstanding by new of Quislings and Petains, allowing themselves to be flattered and used for propaganda purposes whilst re-enforcing the legitimacy of the dictators.

Churchill defined an appeaser as “ one who feeds a crocodile — hoping it will eat him last.”

To those making their accommodations and deals with dictators and autocrats, be clear that this war in Europe – with tens of thousands of re-enforcements from North Korea – the world’s most repressive regime and which I have visited four times and have written a book about – is not simply a threat to the sovereignty of the fledgling democracy of Ukraine but to all the free nations of Europe and all democratic nations.

If Ukraine falls to a tyrannical regime watch what happens to Taiwan, to the Republic of Korea, and to small independent nations who will be picked off, one after another. That’s why friends of Ukraine pay heed to their right to defend their lawful borders and stand with them as they do so.

Listen again to Ronald Reagan, who knew the foolishness of failing to learn the lessons of two world wars which began in Europe:

“We’ve learned that isolationism never was and never will be an acceptable response to tyrannical governments with an expansionist intent.”

And he warned of “rushing to respond only after freedom is lost.”

Europe’s architecture for freedom bequeathed by the blood of its allies and by the wisdom and deeds of Churchill, Habsburg, Adenauer, De Gaspari, Schuman and others, is such a precious legacy.

But it is a legacy that has come at an enormous price. I repeat, freedom is never free. As I saw again at the House of Terror today we must never forget our past and remember what has gone before. I was especially moved to see the place where Cardinal József Mindszenty – imprisoned for years by both fascists and communists- had been tortured. As a boy, I remember how in our parish church in England we prayed for him at the end of Mass each week.

The suffering of the past is woven into the fabric of our contemporary lives. – not least in places like China where ten Catholic bishops are still imprisoned, detained or missing in a state which persecutes people of all faiths.

The past is personal in so many ways.

After the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939, my father and his four brothers enlisted in the British Armed Forces. One lost his life. My father was at the Battle of Monte Casino and spoke about the extraordinary bravery of Polish soldiers.

In the 60s I read about the 1956 Hungarian uprising, the imprisonment of religious and political dissenters and, in 1968, as a schoolboy, organised a town protest following the crushing of Alexander Dubček’s Prague Spring by Soviet tanks.

As an MP, I once met Vaclav Havel, who said that under Communism the truth had become the first casualty: ‘The saving message is that the truth prevails for those who live in truth,’ adding that, in the formation of the next generation of leaders, this message ‘might be inscribed on the Moses baskets of every nation’s babies.’ But do we?

How easily we forget.

In Post War Europe and in Post Communism Europe there was an instinctive embrace of the biblical injunction that “the truth will set you free”.

This was accompanied by remarkable energy, altruism, and generosity in the strenuous efforts of leaders like Churchill and Habsburg. We see it in the Marshall Aid Programme, the rebuilding of cities, towns, and villages, in the rebuilding of economies, institutions, culture, and families.

We will need to see it again if we are to tackle the catastrophic displacement of over 120 million people worldwide; if we are to rebuild Ukraine; if we are to respond to the catastrophic situation in Sudan where an almost unreported war has left 12 million displaced people facing famine; if we are to respond to the dangers in the Middle East, or to the recurring military provocations and threats experienced by Taiwan and South Korea on a daily basis.

We seem very badly prepared to meet these threats. Recall that Churchill said that the very worst time to create a plan is when the plan is needed.

But the threat is not from tyrants alone. There is an interior challenge too. We in the West have an intrinsic problem in the lack of resilience and even belief in our civilizational values. We combine a self hatred with amnesia, forgetting who we are and what made us who we are.

Winston Churchill uttered a warning which has a particular contemporary resonance:

“When one generation no longer esteems its own heritage and fails to pass the torch to its children, it is saying in essence that the very foundational principles and experiences that make the society what it is are no longer valid. What is required when this happens and the society has lost its way is for leaders to arise who have not forgotten the discarded legacy and who love it with all their hearts.”

Do we form tomorrow’s leaders? Do we pass on the torch to those who follow?

Otto von Habsburg knew the importance of this too. I recall with fondness that as a young MP, I met him during a visit to the European Parliament. We discussed a wide range of issues but several times in our conversation he emphasised the importance of the renewal of faith in reanimating the “soullessness” of Europe and its political life.

Your government here in Hungary adopted a new constitution that recognised your nation’s submission to the Cross of Christ.

But, Giscard D’Estaing rejected the advice of six countries to recognise Christianity in its treaties and to rework the foundations accordingly – on rock or on sand.

In their different ways, both Habsburg, the true believer and Churchill, the self-defined buttress of the church, understood why such values give meaning to our identity and lives.

Both knew of a Power greater than theirs. Otto said that you can’t have human rights without God – because He is the ultimate authority; the point of reference.

In these days of Putin’s horrific war, this era of continuous crisis, Europeans are once again faced with an intensifying storm, threatening the foundations.

If its institutions are to have a future, built on rock rather than sand, it needs a revaluation, a metanoia – a change of heart and a change of direction: institutional yes, but personal too.

Otto told me during our conversation that he mourned the decreasing belief in the sanctity of every human life – from the womb to the tomb.

He told me that the family is the building block of society: that we must do more to empower families – including the radical and meritorious idea of giving every child a vote, to be used on their behalf by their parents until the child comes of age.

That would certainly massively counter the anti-family and anti-child agenda so prevalent in so many countries today – and Otto would certainly not have been silent about some of the madness emerging from Brussels today or about the hedonism that has displaced faith, hope and charity.

Habsburg once remarked:

“Neither Communism in the East nor the consumer economy of the West is giving a valid answer to the final questions of mankind. If Communism was shattered because a godless system cannot survive, that is also true of the materialist format that certain market idolaters want to give to the European Community.

Naturally we need a free and social economy, for that is the only kind that works and serves people. But a Europe without Christianity would have to collapse like a house of cards, because it would have no soul.”

This soulless Europe is largely silent about the root causes of the 120 million people currently displaced worldwide – by war, conflict, or persecution, including the 360 million Christians who last year experienced ‘high levels of persecution and discrimination’ worldwide, many the victims of ideological Jihadism or Communist ideology.

Hungary has understood such persecution while others have looked away and deeds have followed words.

It has helped to rebuild the post-genocide villages of Christian on the Nineveh Plain, and it has challenged political indifference to persecution – and I pay tribute to the work of Hungary Helps.

But it has failed to build a consensus around that question so close to Otto von Habsburg’s heart, how do you ensure that the Judaeo-Christian faith that was once central to European life can be presented in ways that unite rather than divide, and whose enduring relevance can appeal to Europe’s increasingly secular and sometimes hostile elites?

How can we best counter that?

Politics must address the anxieties of the age and provide a compelling, hopeful, narrative.

When it fails to do that, it opens the door to populists, autocrats, and dictators.

Otto von Hapsburg’s was deeply concerned for the soul of Europe and so should we be too.

It’s not too late to bring alive the spiritual heart that is the lifeblood of liberty and human dignity.

I began with some anecdotes about Winston Churchill’s rapier-like retorts and humour.

Let me end with some words of his too:

George Bernard Shaw once sent him a note with an invitation to see Shaw’s opening night performance of Saint Joan. The playwright enclosed two tickets, “One for yourself and one for a friend – if you have one.”

Expressing sorrow at being unable to attend, Churchill wrote back and asked for tickets for the play’s second night – “if there is one.”

Well, I have made it to the end of not one but two speeches.

In reiterating my thanks for the privilege of speaking at this Gala Dinner, I would like to end with Churchill’s insistence that “Success is not final; failure is not fatal: it is the courage to continue that counts” and I ask you to raise your glasses to the indomitable courage of Sir Winston Churchill and to toast his memory on the anniversary of his 150th birthday – celebrating, too, his friend and contemporary, Otto von Hapsburg.

===================================================================================

-Budapest and the House of Terror –

The Fascist Arrow Cross Party and the Hungarian Communist Party – two sides of one coin