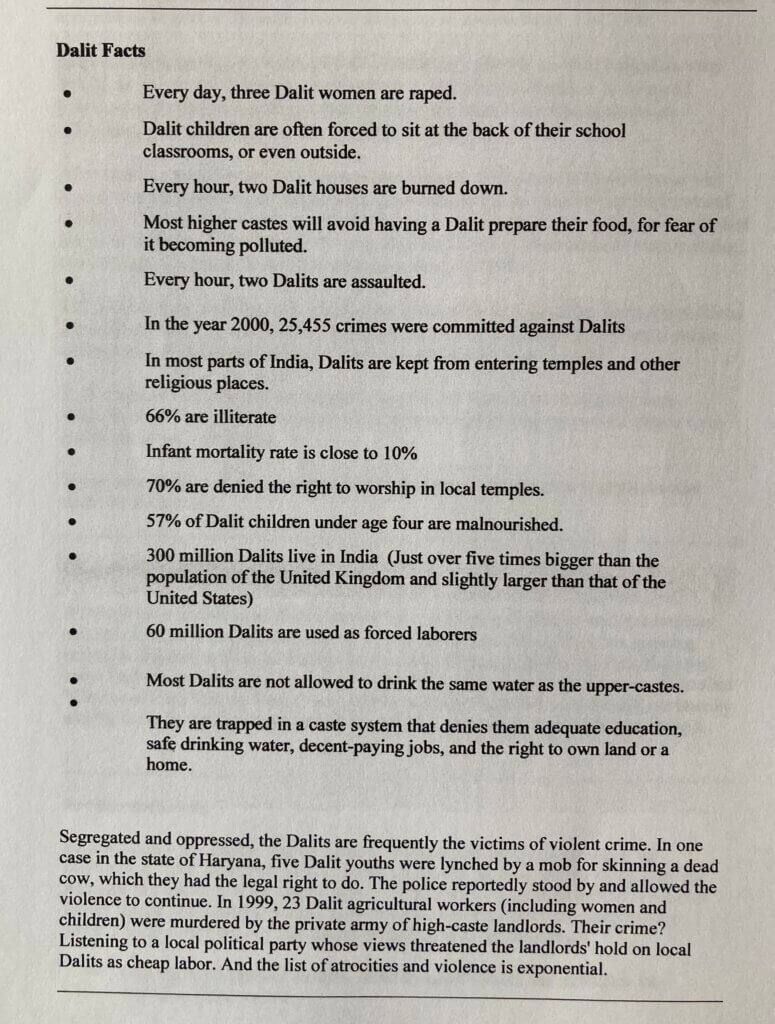

DFN UK and Dignity Freedom Network have helped me update the 2024 Statistics concerning the plight of India’s Dalits. Headlines: 1 crime is committed against a Dalit every 18 minutes.13 Dalits murdered every week.27 atrocities against Dalits every day.According to India’s National Crime Records Bureau , some 45,935 cases of violence are recorded each year. Violence against the Dalit is a tragic, daily occurrence

“In India, around ten Dalit women are raped each day,” says Pallical. National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights

It starts from when they are children,” Pallical says. “They are not allowed to sit at the front of the class, they are not allowed to eat with others, or play with kids from other castes. Very quickly, cliques form, and the Dalit are excluded.

The Dalit: Born into a life of discrimination and stigma | OHCHR

Many high caste Hindus will still not eat food cooked by Dalits. There are reports in the press of students boycotting school meals that were prepared by Dalit cooks.

Tamil Nadu students refuse to eat breakfast prepared by Dalit cook – India Today

1 crime is committed against a dalit every 18 minutes.

13 dalits murdered every week.

27 atrocities against Dalits every day.

National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights – NCDHR

Infant mortality rates (IMR) among Dalits are significantly higher than those of more privileged groups. The Dalit IMR is approximately 45 (deaths in 1,000) compared to 32 for the general category.

Sixty percent of India’s Dalit children are anaemic – compared to a national average of 50 percent.

The literacy rate among Dalits is 73.5%, which is lower than the national average of 80.9% (Census of India, 2020).

The land ownership rate among Dalits is only 2.2%, compared to the national average of 17.9%.

Socio-economic Overview of Dalits in India – Round Table India

Even today, most temples in India do not allow Dalits to enter.

Why this India priest carried an ‘untouchable’ into a temple – BBC News

To this day, Christians from different castes worship in different locations and bury their dead in separate graveyards in some Southern Indian congregations.

Dalit Christians Fill the Indian Church’s Pews. Not Its Pulpits. – Christianity Today

Dalits comprise the majority of agricultural, bonded, and child labourers in the country. Many survive on less than US$1 per day.

According to unofficial estimates, more than 1.3 million Dalits – mostly women – are employed as manual scavengers to clear human waste from dry pit latrines.

India: ‘Hidden Apartheid’ of Discrimination Against Dalits | Human Rights Watch (hrw.org)

Forced or bonded labour is interlinked with the caste system in south Asia and especially affects the 250 million Dalits, whose exclusion and poverty force parents and children into bondage to repay loans from higher castes or simply to survive.

Why hasn’t caste discrimination against Dalits been outlawed in Britain? (inews.co.uk)

In parts of India the ‘two tumbler’ system still exists, whereby Dalits cannot use cups that are used by the upper-castes in cafes and businesses.

Dalits are often refused access to drinking water in villages.

Here were many of the same statistics, twenty years ago, in 2004….India has made great strides in so many respects but much more needs to be done to break the shackles and legacy of untouchability:

2007

2010 – after a visit to West Bengal I wrote:

At several of our meetings I spoke about the plight of India’s untouchables – the Dalits – and the forms of exploitation and slavery which stem from the caste system.

Dalit is a term which derives from a Sanskrit word meaning “broken” or “crushed.” One in forty of the world’s population is a Dalit living in India – a quarter of India’s population.

I recalled that on June 22nd 1813, Wilberforce made a major speech in the House of Commons about India. In his remarks he said that the caste system:

“must surely appear to every heart of true British temper to be a system at war with truth and nature; a detestable expedient for keeping the lower orders of the community bowed down in an abject state of hopelessness and irremediable vassalage. It is justly, Sir, the glory of this country, that no member of our free community is naturally precluded from rising into the highest classes in society.”

Two centuries later India’s President, Dr.Manmohan Singh has trenchantly argued that “untouchability is not just social discrimination; it is a blot on humanity”

Yet, in 2010, while India is a rising world power and is rightly gaining a reputation for innovation and excellence in many fields, this “blot on humanity” disfigures India’s reputation and has become one of the world’s greatest human rights challenges. Hundreds of millions of people remain imprisoned by the bondage of what Wilberforce called “the cruel shackles” of the caste system.

Those shackles inevitably lock their prisoners into the most menial forms of labour, trap them in servitude, and leave them susceptible to innumerable forms of exploitation.

In fairness to the Indian Government, growing social mobility and a series of remedial measures introduced since independence have provided some amelioration. A few individual Dalits have reached high positions in Indian society, not least Justice K.G. Balakrishnan, the senior judge of India’s Supreme Court and Ms Meira Kumar, Speaker of the Lok Sabha, the lower house of India’s parliament. Yet, as I heard first-hand, even where Dalit people are securing elementary education, in some cases further educational progress and employment opportunities have been blocked to them.

Few would surely disagree that the caste system, with all the social prejudices and hierarchies which it entails, continues to enforce and compound servitude and exploitation. The perpetuation of humiliating descent-based occupations is the natural and inevitable consequence of the caste system. The rationale for caste was the division of labour, but to paraphrase Dr B.R. Ambedkar, architect of India’s constitution and hero of the Dalits, caste came to enforce a division of labourers.

This division of labourers has led to Dalits having to undertake one of the most appalling and disgraceful forms of labour anywhere in the world, known euphemistically as manual scavenging. It involves cleaning human excrement from dry latrines, and is uniquely performed by Dalits as a consequence of their caste. The number engaged in this occupation is not known for certain, but it may be as high (or higher) than the equivalent of the population of Birmingham. It is an occupation reserved from Dalits – and it is a job undertaken for life, with around 1.3 million people employed as scavengers. They are caught in a vicious circle. While they do the work there is no incentive to introduce modern sanitation and while they do the work they remain “untouchables.”

Tens of millions of India’s citizens are subject to highly exploitative forms of labour and modern-day slavery. This often plays into the problem of debt bondage and bonded labour, which affects tens of millions: it perpetuates a cycle of despair and hopelessness, as generations are bonded to the family debt, unable to be educated, unable to escape. Tragically, the debt is often the result of a loan taken out for something as simple and essential as a medical bill.

The caste system also plays into people trafficking – another form of slavery which affects millions in India. According to a report in CNN Asia last year, India’s Home Secretary Madhukar Gupta “remarked that at least 100 million people were involved in human trafficking in India”, whether for sex or for labour. The head of the Central Bureau of Investigation said that India occupied a unique position as a source, transit and destination country for trafficking, and that India has more than three million prostitutes, of whom an estimated 40% are children. These statistics are hugely significant: the situation in India simply must be at the heart of the fight against trafficking globally.

The Dalit Solidarity Network UK, which has been calling for an end to the caste system before this year’s Commonwealth Games, also highlights devadasi – a system of ritual prostitution of almost exclusively young Dalit girls.

During their time in India the British failed to heed Wilberforce and resisted the calls to abolish caste. Although untouchability was barred by the constitution when India secured independence, in 1947, the caste system was not dismantled. Most of the worst forms of exploitation are proscribed by Statute but all too often, the laws are simply not implemented, and the police further entrench, rather than protect against, caste prejudice. This point was made repeatedly in the Concluding Observations of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination in May 2007.

A damning verdict is reached by a recent, in-depth report by the Robert F. Kennedy Centre entitled ‘Understanding Untouchability: A Comprehensive Study of Practices and Conditions in 1,589 Villages’: it describes “the Government of India’s continued ignorance about the depth of the problem and inadequacy in addressing untouchability and meetings its legal obligations in regard to the problem of untouchability”.

Caste discrimination is usually associated with India but, in parenthesis, I might add that there are also an estimated 3.5-5.5 million Dalits living in Bangladesh (2.5-4% of the total population). The majority are landless, and live in chronic poverty in rural areas or urban slums. They are deprived or actively excluded from adequate housing, health care, education, employment and participation in public life. Approximately 96% are illiterate.

In my study I have a small terracotta pot given to me by Dr.Joseph D’Souza, President of the International Dalit Freedom Network. Such pots must be broken once a Dalit has drunk out of it – so as not to pollute or contaminate other castes. This, in the 21st century. It’s not the pots which need to be broken, nor the people, but the system which ensnares them.

2014:

2017 I wrote:

Dr. Ambedkar, the architect of Indian Constitution once remarked that “Untouchability is far worse than slavery, for the latter may be abolished by statute. It will take more than a law to remove the stigma from the people of India. Nothing less than the aroused opinion of the world can do it”

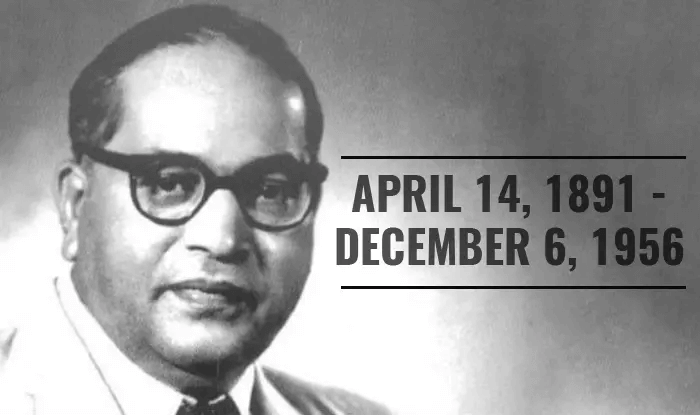

Ambedkar’s life was a life of relentless struggle for human rights. Born on a dunghill and condemned to a childhood of social leprosy, ejected from hotels, barber shops, temples and offices; facing starvation while studying to secure his education; elected to high political office and leadership without dynastic patronage; and to achieve fame as a lawyer and law maker, constitutionalist, educator, professor, economist and writer, illustrates what the human spirit can overcome.

Ambedkar made untouchability a burning topic and gave it global significance. For the first time in 2500 years the insufferable plight of India’s untouchables became a central political question.

Ambedkar understood that the great nation of India would never achieve its potential if it remained disfigured and divided by caste. Without freedom to marry, who they would; to live with, who they would; to dine with, who they would; to embrace or touch, who they would; or to work with, who they would, the nation could – and can – never be fully united or able to fulfil its extraordinary potential.

While still a young man of twenty, Ambedkar perceptively wrote: “Let your mission be to educate and preach the idea of education to those at least who are near to and in close contact with you.” He said that social progress would be greatly accelerated if female and male education were pursued side by side. He later insisted that “We will attain self elevation only if we learn self-help, regain our self-respect, and gain self knowledge.”

Although Dr. Ambedkar was able to have India’s Constitution and the laws framed to end untouchability, for millions and millions of people, many of those provisions have not been worth the paper on which they are written.

Ambdekar’s own struggle may now be history; caste is not. In our generation it is surely time to make caste history.

2020: House of Lords (Short Debate on 25 February 2020) I said:

As India celebrated its Republic Day on 26 January, marking the 70th year since the ratification of the Indian Constitution in 1950, a disturbing counterpoint was in evidence on the streets of that great country: the world’s largest democracy.

India’s founding fathers, Gandhi, Nehru, Ambedkar, Subhas Chandra Bose and Vallabhbhai Patel, who steered their new nation in a direction that ensured it wasn’t destroyed by sectarianism, casteism and authoritarianism, would surely be aghast to see people all over India protesting against a draconian law that is communal and unconstitutional in its nature – the Citizenship (Amendment) Act 2019 and the proposed nation-wide National Register of Citizens (NRC).

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the father of India’s Constitution warned Indians against “ any competitive loyalty whether that loyalty arises out of our religion, out of our culture or out of our language. I want all people to be Indians first, Indian last, and nothing else but Indians.”

He wisely said that “The Constitution is not a mere lawyer’s document, it is a vehicle of life, and its spirit is always the spirit of the age.”

Tragically, today’s Government is living by different principles and a different spirit, stoking fear among all quarters of society across the country. There have been reports of numerous arrests, excessive use of force by the police and deaths, as a result of these protests.

The Citizenship (Amendment) Act is in itself discriminatory, isolating Muslims including Rohingya, Ahmadiyya, Shi’as and other minorities from participating in nation building. Take it together with the National Register of Citizens, and it is abundantly clear that both measures will have far reaching implications for all sections of the community right across the nation, in the only place that they can call home.

With the launch of these unreasonable and extreme benchmarks for citizenship, many who do not possess the necessary documents to prove their citizenship, risk facing statelessness and immeasurable suffering in detention centres, and an imminent unsettled future.

Right across India this will not only burden millions, who are already suffering extreme hardship, but will also set them aside from the rest of society – as if there weren’t already too many existing barriers preventing citizens from being “Indians first, Indian last, and nothing else but Indians.”

With CAA/NRC policy in place, the minority population of India, which comprises of approximately 20% of the total, with a large percentage of them economically poor and socially excluded, will make large swathes of Indian society into outsiders and more vulnerable than ever.

The Preamble of the Constitution of India opens with the words, “We the people of India”. It doesn’t say, in words which could have been crafted by today’s Government: “We the documented people of India.”

Ambedkar’s Constitution, was never intended to discriminate between Indian citizens on the basis of their religion.

This law not only discriminates against Muslims, but also diminishes a Muslim person’s value in society, inevitably exposing the community to further prejudice.

The promotion of majoritarian communalism, based on anti-minority rhetoric, has been evident since 2014 when the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power.

Since 2019, after taking office for the second term, the Party’s leadership have thrown caution and wisdom to the wind.

This has emboldened others.

There have been attacks, perpetrated by non-State actors such as cadres of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. The RSS is closely connected to the ruling party as well as commanding influence over the police in many parts of the country, which endangers public trust in the impartiality, independence or objectivity of the Police: dangerous for any society.

There have been widespread reports of attacks on the freedom of worship, religion or belief; hate speech; mob lynching; targeted violence against the Dalit and Tribal communities; assassination, and attempted assassination, of journalists and human rights defenders; and infringements of freedom of expression against those who raise their voices in dissent against such rank injustice.

Anyone who questions the policies of the government risk being labelled an ‘anti-national,’ and subject to harassment and brutal attack, by nationalists groups.

The unprecedented attack of students at the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) on January 5 by a large mob of unidentified assailants armed with stones and sticks is just one shocking example of the shrinking space for public dissent against injustice. It gives forces to Nehru’s own remark that “The only alternative to coexistence is co-destruction”

Great Britain’s longstanding relationship with India is hugely significant and does not always reflect well on us.

But, it is precisely because we must all learn from the past that in our own times we should not hold back when we see human dignity and diversity at risk.

Relationships between States must be woven into an explicit understanding that democratic values of justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity, foundational ideals to nation building, must be preserved, protected and promoted at all cost.

At a time when hate and intolerance are so much in evidence in so many parts of the world – often fanned by xenophobic agendas – we must, as India’s good friend, urge its Government not to abandon the high ideals of its Constitution.

My noble friend is right (the Earl of Sandwich) is to be thanked for giving the House the change to carefully consider the implications of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act and the National Register of Citizens on the citizens of India