See:

Roscoe Reflections: Roscoe Lecture at Liverpool’s St.George’s Hall – Thursday October 5th 2023 -marking the bicentenary of the Liverpool Mechanics Institute -and which evolved into Liverpool John Moores University. Delivered by David Alton (Lord Alton of Liverpool).

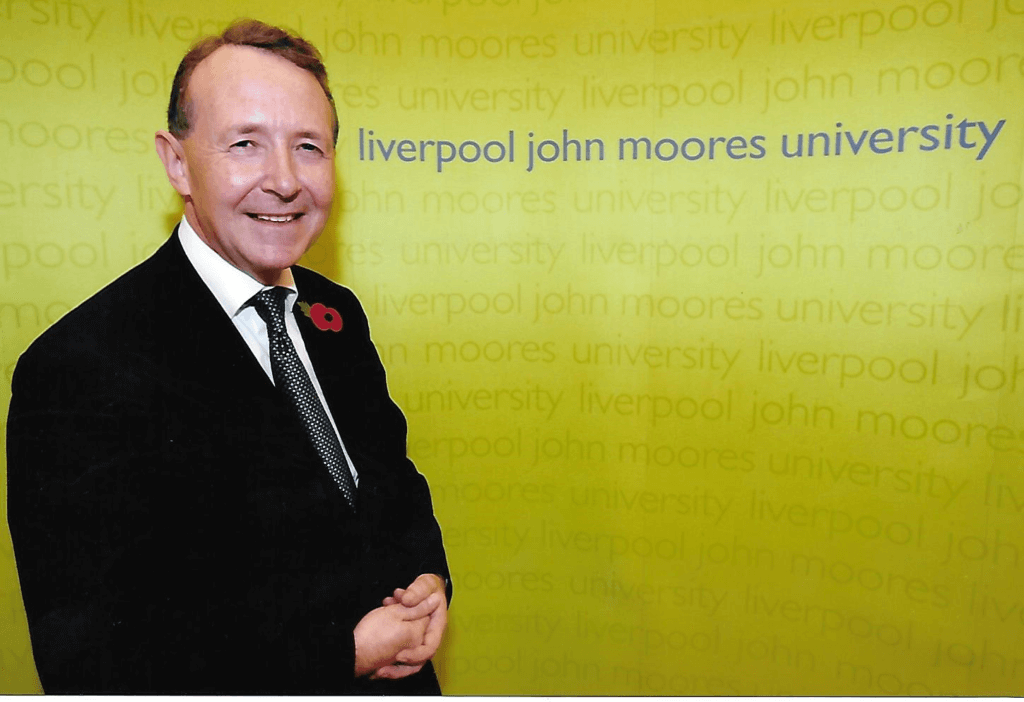

Vice Chancellor, Distinguished Guests, it’s a signal honour to have been invited to deliver this Roscoe Lecture in Liverpool John Moores University’s bicentenary year.

Professor Mark Power has set me the invidious task of reflecting on the origins of these Roscoe Lectures – and having overseen around 140 of them – to try and highlight some of the key moments in a public lecture series that has no recent rival in terms of scale and breadth.

At the very outset I should pay tribute to friends and colleagues who made them such a success – not least Mrs.Barbara Mace. Some of them here tonight – including Rob McLoughlin of Granada TV who hosted the Q and A – were present for the very first Lecture, entitled “Educating for Citizenship” and delivered in the Town Hall on November 12th, 1997.

I always cautioned lecturers not to go on too long and to leave time for questions – advice I will give myself tonight.

On one occasion, in 2002, the constraints of time were demonstrated by a large prop.

We had filled the Liverpool Philharmonic Hall to hear Ken Dodd lecture on the place of humour in sustaining us in dark times.

Ken was well known for keeping audiences laughing for hours beyond the advertised finishing time.

I had repeatedly emphasised to him that the orchestra had a rehearsal in the Hall after we had finished and that we had organised a dinner to celebrate his birthday, that we needed to end on time.

As we came out onto the stage Ken headed over to the side curtains, put on a gown and mortar board and wheeled onto the stage a wheelbarrow with a very large egg timer.

Without uttering a word, he placed it on the table next to me, and as the sand began to work its way through, looked out at the audience, who immediately saw the joke at my expense and roared with laughter.

One of the great lawyers at the Nuremberg Trials, Lord Birkett – a brilliant advocate and humane judge – once told his audience “I do not object to people looking at their watches when I am speaking. But I strongly object when they start shaking them to make certain they are still going.”

So, in the absence of Ken Dodd’s egg timer, I will be on the lookout for the shaking of watches.

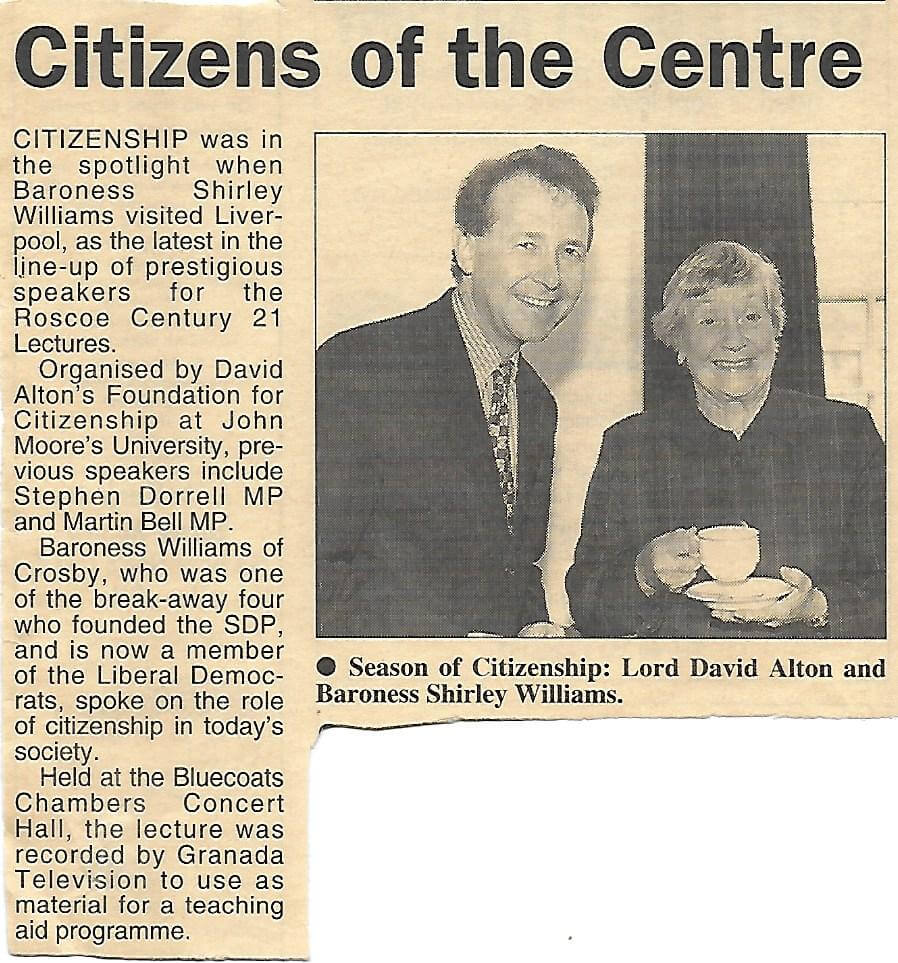

The Rule of Three is a powerful technique or principle used in public speaking – Shirley Williams used it for her Roscoe Lecture in the Bluecoat Chambers – saying that as Gaul had been divided into three parts, she would do the same.

The point is that any ideas, thoughts, events, characters, or sentences that are presented in threes are said to be more effective and memorable.

So let me outline the three elements of my remarks tonight as the Why, Who and What

Why did we launch the Roscoe’s?

Who did we want to give the lectures?

What do I hope is their legacy and future?

Why?

Intending to stand down from the House of Commons in 1997 I had undertaken a Visiting Fellowship at St. Andrew’s University and had begun work on a new book on citizenship. Meanwhile, I had supported Peter Toyne’s ambitious ideas for Liverpool Polytechnic to become a home-grown university.

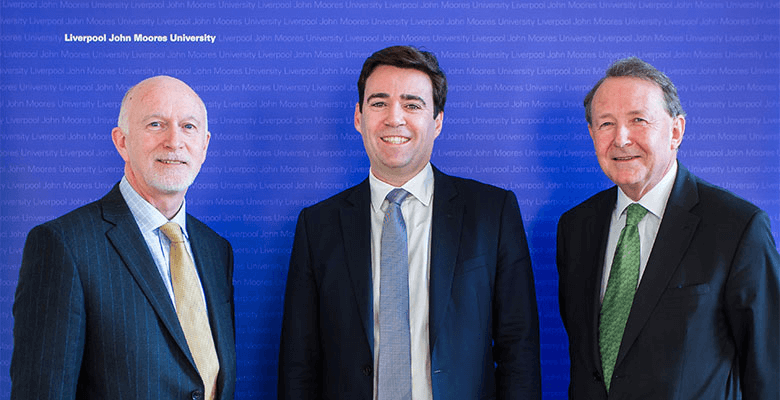

The city owes Peter a tremendous debt on many fronts and I’m thrilled to see him here tonight. Like his successors – Michael Brown who is also present – Peter gave me wholehearted support.

Although LJMU is a new institution it has its origins in 1823 and the creation of the Liverpool Mechanics’ Institute and College of Arts. Hence the bicentenary.

We had discussed the creation of a Foundation for Citizenship and with the generous help of the Liverpool lawyer, E. Rex Makin – and it is wonderful to also see his widow, Shirley, here today – the Foundation was established.

The Institute’s 1823 mandate was that education is the key to progress – and as someone who was the first from either side of his family to have a higher education – as a beneficiary of the 1944 Education Act – I wholeheartedly affirm that.

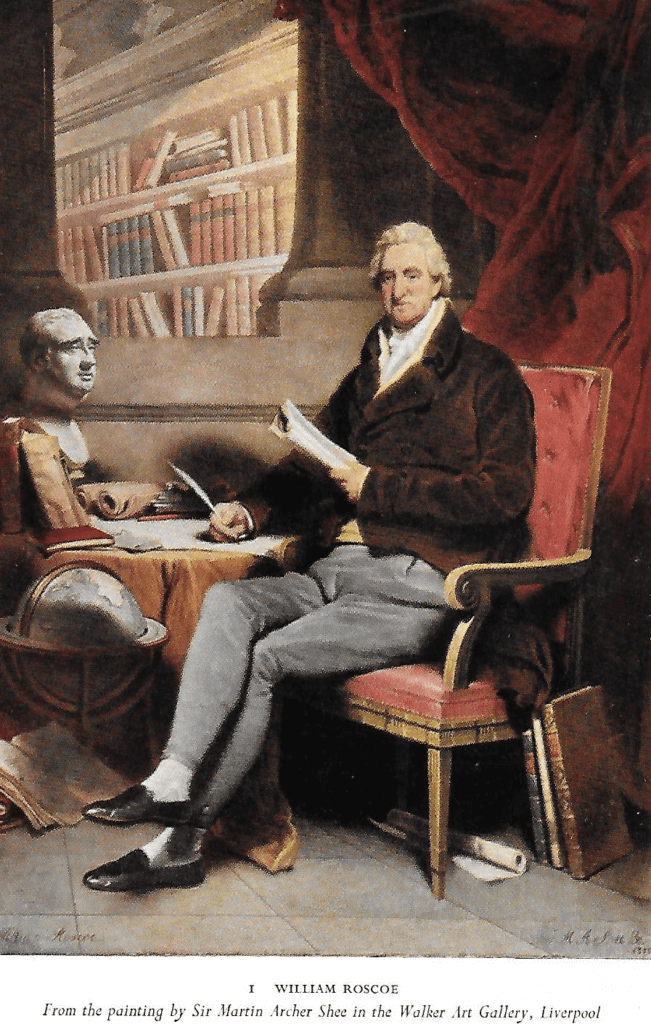

One of its founders was William Roscoe.

The Institute ran public lectures and classes which explored the arts, humanities, technology, engineering, the science of medicine and physiology and philosophy. Up to 1,400 people regularly attended.

In 1844, eleven years after the Institute’s foundation, Charles Dickens gave a lecture and told his audience “ It’s a delight and happiness for me to connect myself with such an institute as this.”

Dickens’ brilliant biographer, Claire Thomlinson, gave a Roscoe lecture here in St. George’s Hall in 2012 to commemorate another bicentenary, the 200th anniversary of Dickens’ birth.

We even discovered a letter he had sent from the Adelphi Hotel in which he said how wonderfully welcoming the people of Liverpool had been but how awful the acoustics had been in St. George’s Hall. Always a challenge!

So, a public lecture series – 174 years after the Foundation of the Mechanics Institute – seemed like a perfect piece of symmetry.

But there was more to it than that.

From the very start LJMU has been ambitious to be more than an army of occupation in the heart of the city.

It has always wanted to play a part in the city’s civic life.

But it was by no means an easy time.

In 1997 we had to face the consequences of a turbulent and discordant period where respect for differing views had often been replaced by anger and intolerance.

If nothing else, by inviting lecturers with differing opinions we hoped we could open up a respectful space but also introduce the visiting speakers to real Liverpudlians and Merseysiders rather than the media caricatures.

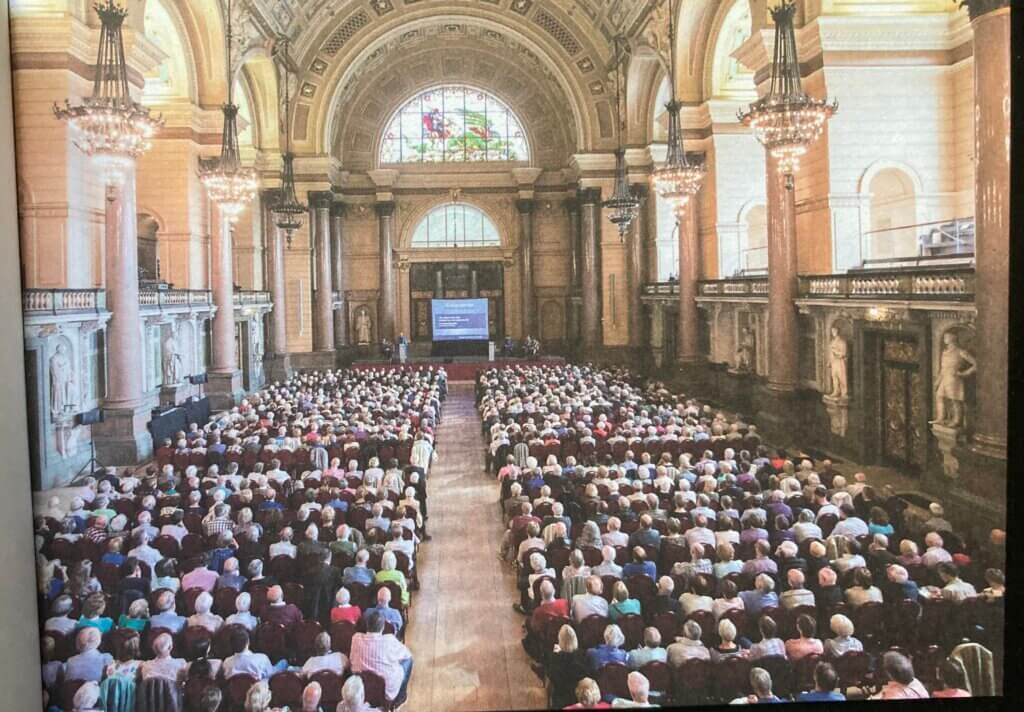

It was a point re-enforced by Melvin Bragg when I showed him this Hall: “But where will the lecture be?” he asked. “In here” I replied.

“But how many are you expecting?”

“Over 1000 tickets are out.”

“Will they listen, will there be trouble?” he tentatively asked.

I was struck that even broadcasters used to speaking into microphones or to cameras reaching millions of people can be intimidated by large public audiences.

Melvin, Roy Jenkins, and many others went away with a very different view of our city and became ambassadors in the remaking of Liverpool’s reputation and image.

The lectures would also be a space in which Merseysiders would rub shoulders and strike up conversations with people they might not otherwise come into contact with.

From the very start I wanted the lectures to be varied and unpredictable but not shy of stimulating thoughtful debate. They should be an example of the university’s insistence on academic freedom and free speech.

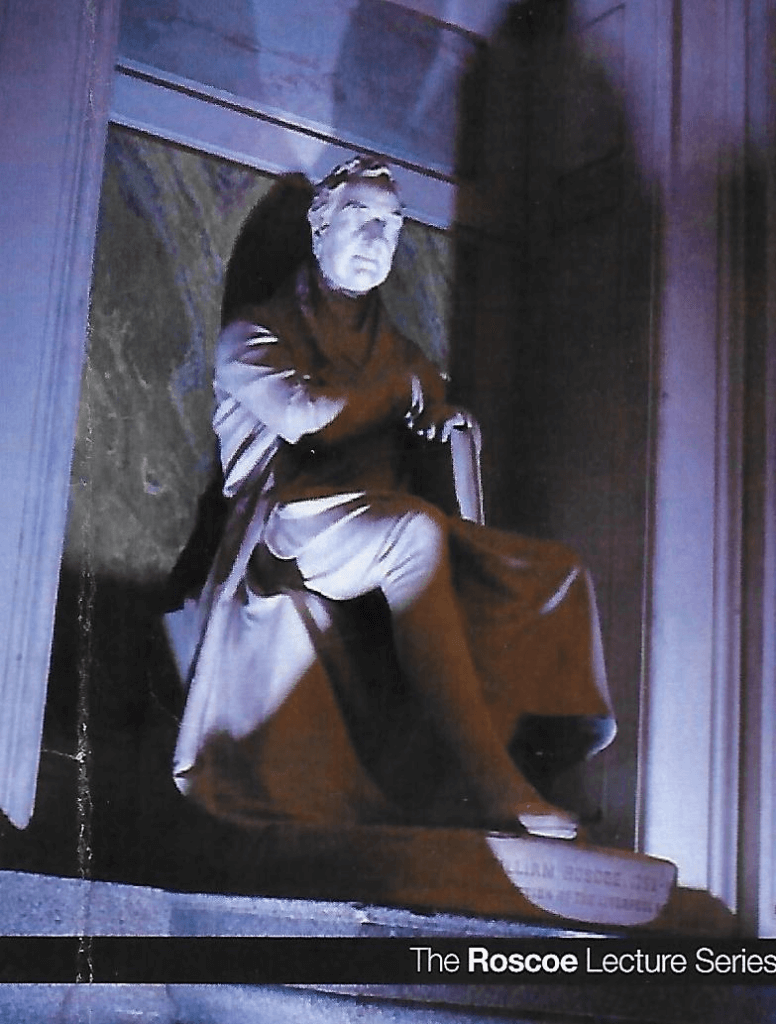

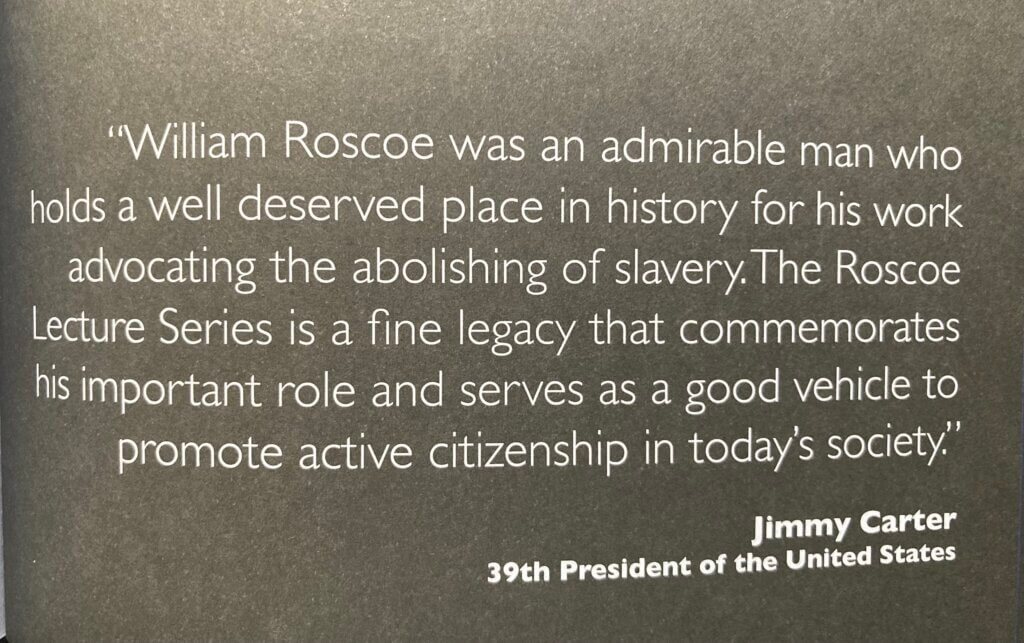

And from the beginning I wanted to name the lectures for William Roscoe, the father of Liverpool culture – and with a direct line of descent into this world class university. The great historian of Liverpool James Picton said that ‘no native resident of Liverpool has done more to elevate the character of the community, by uniting the successful pursuit of literature and art with the ordinary duties of the citizen and man of business’.

In 1807 Roscoe was briefly elected to the House of Commons and during the few weeks he sat as an MP he was able to vote with the abolitionists to end the transatlantic trade. His role helps to redeem the darkest chapter of Liverpool’s story.

Roscoe told the house of Commons: ‘I consider it the greatest happiness of my existence to lift up my voice on this occasion, with the friends of justice and humanity.’

The slave traders dominated Liverpool and it was highly unpopular to speak out against it. He and William Rathbone were two of the few who did. Roscoe, a Unitarian, went further and joined with the Quakers, and political leaders like Fox and the Christian political reformer, William Wilberforce, to challenge the slavery laws.

On returning to Liverpool, he was beaten up by an angry mob and never re-elected.

In the years left to him he continued to publish tracts and poems attacking the inhumanity and evil of slavery.

In his poem The Wrongs of Africa are lines which retain their strength and poignancy to this day: ‘Blush ye not, to boast your equal laws, your just restraints, your rights defended, your liberties secured, whilst with an iron hand ye crushed to earth the helpless African; and bid him drink that cup of sorrow, which yourselves have dashed, indignant, from Oppression’s fainting grasp?’

Roscoe, a Unitarian, showed admirable courage as he shunned popular acclaim, vigorously admonishing his Liverpool readers and reminding them that for all of us there comes a time of reckoning: ‘Forget not, Britain, higher still than thee, sits the great Judge of nations, who can weigh the wrong. And can repay.’

Roscoe’s remarkable story – including his role in founding the Botanic Gardens and the Athenaeum and his links with Lorenzo de Medici and Leonardo de Vinci and Roscoe’s discovery of that polymath’s lost treatise on mechanics – is told on my web site (see: https://www.davidalton.net/2010/12/23/the-life-of-william-roscoe-father-of-liverpool-culture/ and https://www.davidalton.net/?s=Roscoe ).

In 2007 we used the anniversary of the abolition of the transatlantic trade to recall both the history of that struggle and the challenge of contemporary modern-day slavery.

We heard from the writer, Adam Hochschild, from Nicholas Frayling, Anti-Slavery International, from Rebecca Tinsley, founder of Network for Africa and Vava Tampa, founder of Save the Congo.

Roscoe had a profound love of Africa and would have approved of them all.

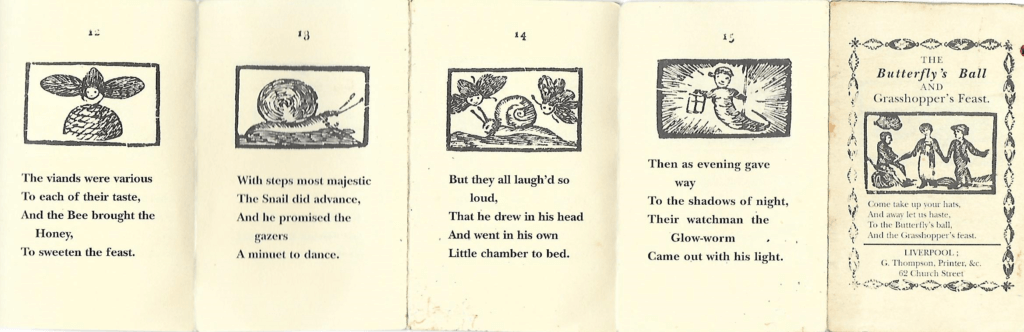

He was also an accomplished botanist – an early environmentalist – and brought nature to life in his captivating children’s poem, The Butterfly Ball, written for his son Robert at their home, Allerton Hall, in which he describes some of the guests at revels in the insect world: ‘And there was the gnat, and the dragon fly too, with all their relations, green orange and blue’

King George III had the poem set to music for his three daughters, the princesses Elizabeth, Augusta and Mary

And Roscoe never stopped trying to challenge the infamies of his times.

In the last three years of his life, we find him busy founding a Liverpool Association for Superseding the Use of Children in Chimney Sweeping – a cause which Lord Shaftesbury would bring to fruition – and a scandal which remains with us today in the sending of children down cobalt mines in the Congo.

So, I had no doubt that I had the right person and the right name for a public lecture series.

And where better to hold them than in an outward looking city animated by passionate argument, love of conversation and quick-witted humour?

But back in 1997 one sceptic guffawed and said that was all very well and good but the days of the public lecture were over, and no one would come. And here we are at the 169th .

With Peter Toyne’s support I went ahead anyway and that first lecture got us off to a good start, although my discouraging sceptic said they would tail off after one or two.

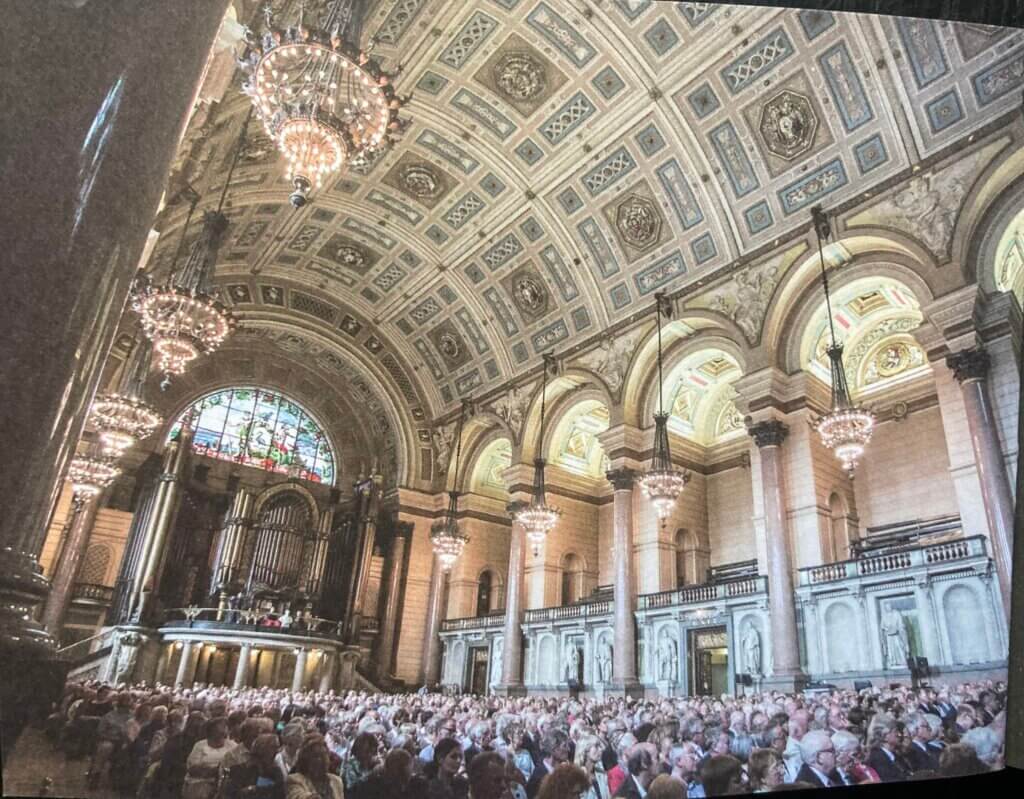

In addition to combining learning and an enjoyable evening out I hoped that by using prestigious venues – like this one, complete with its statue of William Roscoe and its Fr. Willis organ (thank you Stephen Derringer for playing us in) – that it would open people’s eyes to our fine architectural heritage and display the city at its best.

But from time to time, it would also showcase some of the academic excellence at LJMU – as with Professor Mike Bode’s lecture in 2006 asking whether mankind’s future is in space – a theme later explored by Martin Rees, the Astronomer Royal, Sir Patrick Moore, Brian Schmidt, Monica Grady, and David Hillmers a US astronaut four times is space.

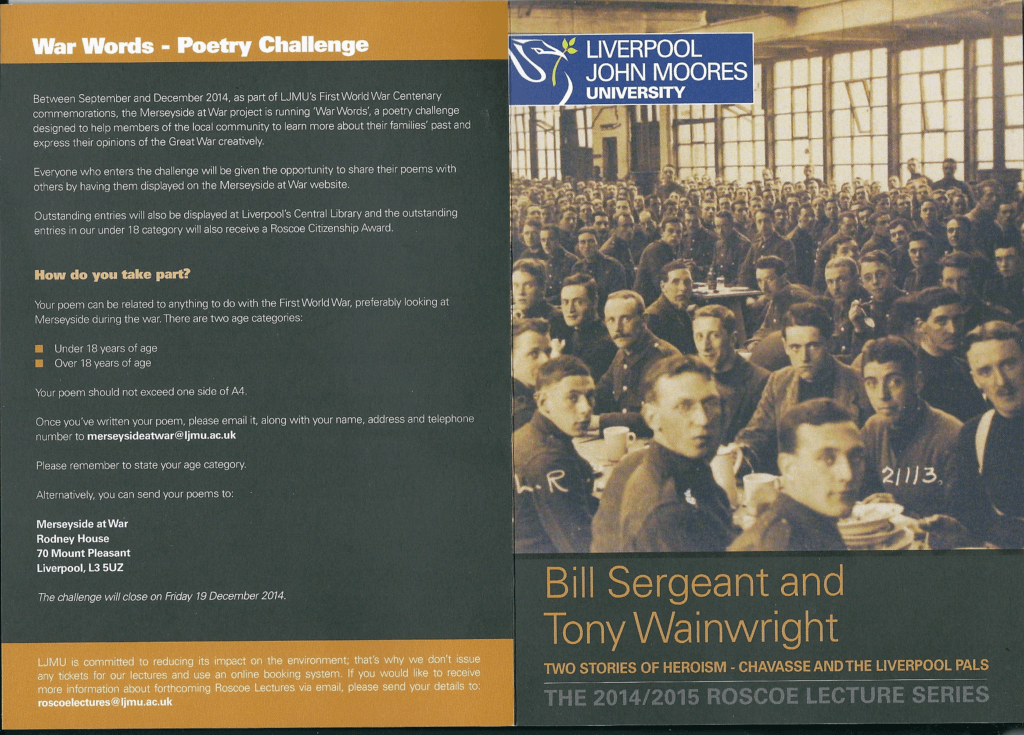

There was a similar collaboration in 2014 with LJMU’s Professor Frank McDonagh in commemorating the anniversary of the First World War – with a day of World War One poetry and moving lectures from Bill Sergeant and Tony Wainwright about the Liverpool Pals and rounded off by the First Sea Lord, Admiral Alan West, and Diane Lees, the first female director of the Imperial War Museum. On a subsequent occasion Jeremy Paxman lectured on the Great War and on the realities of war – much on our minds today because of Ukraine. We heard from the former Chief of Staff, Field Marshall Lord Guthrie, from George Robertson, the former head of NATO, and the Duke of Westminster on the role of the territorial army.

Why the Roscoe Lecture? It was to explore serious and important questions like these.

That takes me from why I founded the lecture series into the who. Who would we invite to give the lectures?

Over 25 series of Roscoe lectures we have heard from heads of State, Cabinet Ministers, celebrated academics, cardinals, archbishops, rabbis and imams, ambassadors and diplomats, novelists, biographers, commentators, sportsmen and women, judges, musicians, comedians and entertainers, businessmen and businesswomen, field marshals, generals, admirals, a couple of Chief Constables and Mayors, some Peers and a Duke, and people who fit no category.

Of course, topping the bill, in 2007 I was pleasantly surprised when Kensington Palace told me that Prince Charles would be willing to accept my invitation to deliver a Roscoe Lecture and to accept a University Fellowship.

In his Roscoe Lecture the future King reflected on public service. He spoke about the struggle against slavery and told us that “Roscoe was considered a fool by many to challenge the received wisdom of his day”.

He added that “architecture, medicine, agriculture, the environment and education…have been adversely affected by the neglect of a particular kind of wisdom that guided our forebears for generations and…in expressing Mankind’s relationship with Nature.”

Public service and citizenship have always been central themes but there have been others – in which we have tried to combine wisdom and words with action and deeds.

So, we had the sculptor Stephen Broadbent describe his reconciliation statues in the three vertices of the slavery triangle and from West Africa we welcomed President John Kufuor of Ghana and conferred on him the university’s highest award.

We explored the barriers to diversity with well-judged lectures from Paul Robeson Jnr, Baroness (Valerie) Amos, George Alagiah – who recently died of bowel cancer, far too young – and Trevor Philipps – who reflected on the lessons we could learn from the killing of Anthony Walker, who was aged 18 when he was murdered in a racist attack in Huyton. And we heard from Tanni Grey Thompson about the prejudice and obstacles faced by people with disabilities.

The theme of reconciliation prompted us to bring President Mary McAleese of Ireland and also Senator George Mitchell who did so much to negotiate Northern Ireland’s Good Friday Agreement. And movingly, we heard from Colin Parry whose son, Tim was one of two children murdered by an IRA bomb in Warrington in 1993 and from John Alderdice, the former Speaker of the Northern Ireland Assembly.

We never shied away from grim reality and terrible tragedy.

After four suicide bombers struck London’s transport network, killing 52 people and injuring 770 others, we ran a short series entitled “learning to live together” and featured the Methodist Moderator, a Muslim Imam and a Jewish Rabbi. On other occasions we heard inspiring addresses from Jonathan Sacks, the Chief Rabbi, from Rabbi Julia Neuberger, the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster and our own local church leaders.

Another former head of State and Nobel Laureate who gave a Roscoe Lecture was Poland’s Lech Walesa, the dockyard electrician from Gdansk who co-founded Solidarity and brought phenomenal change to his country as it reclaimed its sovereignty.

Anne Applebaum in her brilliant account of the Soviet gulags left us in no doubt about the nature of Stalin’s Soviet empire while Ambassador John Everard gave us a harrowing account about the nature of crimes against humanity in North Korea today.

Justice, the rule of law, and human rights were themes brought to life by lecturers like Cherie Booth KC and Lord Justice Sir Brian Levison KC – who both served as Chancellors of LJMU – and we were inspired by the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Louis Marino Ocampo, by Shami Chakrabati, by Sir Mark Hedley, by Helena Kennedy KC and Patricia Scotland KC – who went on to become Secretary General of the Commonwealth. And we heard from two distinguished Chief Constables, Lord Hogan Howe and Sir Jon Murphy.

We heard from survivors of Holocaust, Genocide, and crimes against humanity – Trudi Levy, Pascal Khoo The and Philomene Uwamaliya – whose accounts of the Hitler’s concentrations camps, Burma’s atrocities and Rwanda’s genocide were among the inspirations for my most recent book, on the crime of genocide.

Susan Cohen used a lecture on the life of Eleanor Rathbone to highlight the role of women in politics. And we had capacity audiences for Michael Heseltine and Andy Burnham. We heard alternative views on Scottish independence from Alex Salmon and Charles Kennedy.

From front line politics we heard from, among others, David Blunkett, Ann Widdecombe, Jack Straw, Geoffrey Howe, Douglas Hurd, David Steel, Frank Field, and John Bercow, the Speaker of the House of Commons. And from the press gallery in Parliament, we heard from the astute observations of Peter Hennessy.

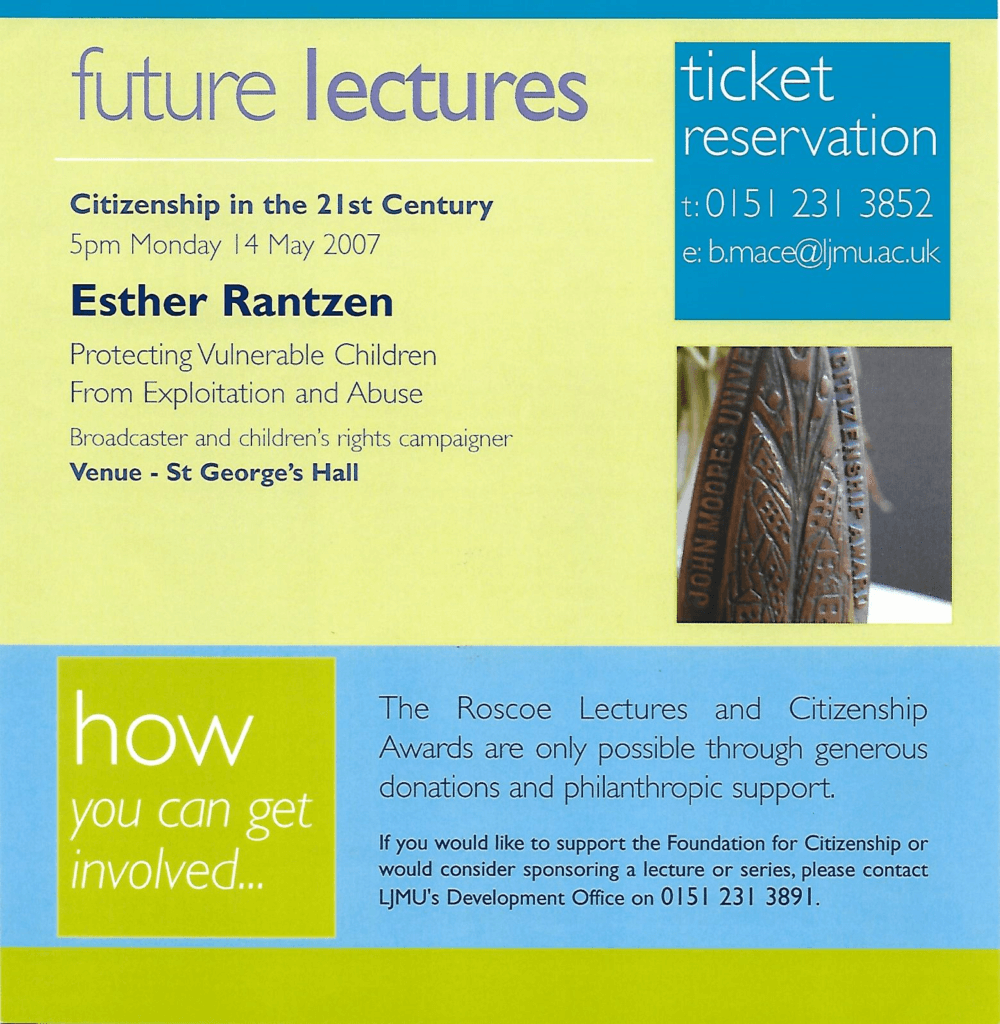

Oher themes of the Roscoe lectures have included social issues – homelessness and poverty addressed by John Bird, the founder of Big Issue; Esther Rantzen on child abuse; mental health challenges by Sheila Hollins; cancer, compassion and care from Ilora Finlay; and Sir Liam Donaldson the Chief Medical Officer, on the legacy of Dr. Duncan.

On June 4th, 2008, Liverpool was named capital of culture – a title synonymous with Roscoe, the “father of Liverpool culture” – and, for the city, an achievement brought about in no small part through Peter Toyne’s efforts.

We celebrated Liverpool’s cultural life through a series of lectures. From the world of music and poetry we heard from Vasily Petrenko, Roger McGough and Ian Tracey; from the media, Peter Sissons, Lord Hall, Charles Allen, Greg Dyke, Joe Riley; from the world of sport, Clive Tyldsley and Gerard Houlier; from gifted writers such as Claire Tomlinson, Sir Simon Jenkins, Brian Appleyard, Frank Cottrell Boyce and the acclaimed children’s writers, Michael Morpurgo and Brian Jacques.

We invited contributions from the world of business and economics, homing in on ethical and social responsibilities – with lectures from Mark Carney, Philip Green, John Studzinski, Sir Peter Middleton, Terry Leahy, John Fleming, Sir Peter Sutherland, and Will Hutton.

So much for the Why and the Who?

What, then do I hope is their legacy and future?

There is one remarkable lecture that I have not mentioned.

In 2004 I invited his Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama to give a lecture on the art of peaceful coexistence and respect for difference.

It was to be held in the Anglican Cathedral in the presence of leaders of all the great faiths.

Thousands applied for tickets.

Just one week before the lecture, Professor Michael Brown, then LJMU Vice Chancellor and Cllr. Frank Roderick, the Lord Mayor of Liverpool both received calls from Chinese Communist Party officials in the Chinese Embassy in London.

Go ahead, they said and there will be no more Chinese students for your university. Go ahead and the twinning of Liverpool and Shanghai will be severed.

What did I think?

I said that when a Chinese gun boat arrived in the Mersey, we should get worried – but capitulating to blackmail and threats would merely give encouragement to the bully.

Besides – unlike the rules that apply in a one-party totalitarian state – we believe in academic freedom and free speech.

The lecture went ahead – with a waiting list of over 1000 people. The Dalai Lama said in his lecture

“Whether we agree with each other, or have differences, we have to live on this planet together as a human society…The reality is we are heavily interconnected and interdependent.”

In the years that followed that lecture I travelled to Tibet and to western China – where I met Uyghur Muslims who are now subjected to genocide. I went to Taiwan, which faces daily military intimidation and was part of the international team that in 2019 monitored the last free elections in Hong Kong.

I love and respect Chinese people and civilisation but not the ideology and cruelty of the CCP.

I worry about their subversion of our institutions – not least our universities – the CCP’s infiltration and influence, and the intimidation which they have used against exiled Hong Kongers.

So, I often think about the words of the Dalai Lama and the essence of free speech and academic freedom – which are encapsulated in the spirit of these Roscoe Lectures.

In an age of no platforming; of hate speech; of political correctness rather than political courage; of the overuse of the flaccid language of rights without reference to responsibilities, obligations and duties; and the absence of respect for others and respect for difference; I hope that the legacy of William Roscoe and the lectures named for him will live on for many years to come.

And I hope the Why, Who and What fulfilled your expectations for this evening together.

Earlier, I mentioned the poem, The Butterfly Ball which William Roscoe wrote for his son Robert.

It concludes by reminding his children that even festivities have their end: “Their watchman, the glow-worm, came out with a light, “Then home let us hasten, while yet we can see, for no watchman is waiting for you and for me”; so, said little Robert, and pacing along, his merry companions returned in a throng.”

Less prosaically – and in the absence of Ken Dodd’s egg timer – I am a fan of the Marx Brothers and I recall that in one of their films Chico is pounding away furiously at the piano.

Meanwhile, the aptly named Groucho looks on impatiently.

Chico continue, regardless, to pound away at the keys.

Finally, he says to Groucho: “I can’t think of the ending.” And Groucho replies “I can’t think of anything else.” And you will be relieved to know, nor can I.

https://x.com/DavidAltonHL/status/1707697885758800366?s=20

https://x.com/DavidAltonHL/status/1709559908935315662?s=20

1997 – the first Roscoe Lecture – by Stephen Dorrell MP

2007 the late George Alagiah delivered a powerful Roscoe Lecture on the theme of respecting difference

1998 the Chief Rabbi, Jonathan Sacks, and a Roscoe Lecture on what makes for good citizenship.

1998 Baroness (Shirley) Williams of Crosby on the role of citizenship in building strong societies