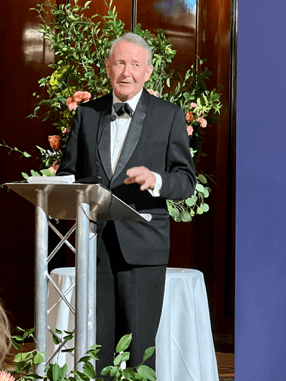

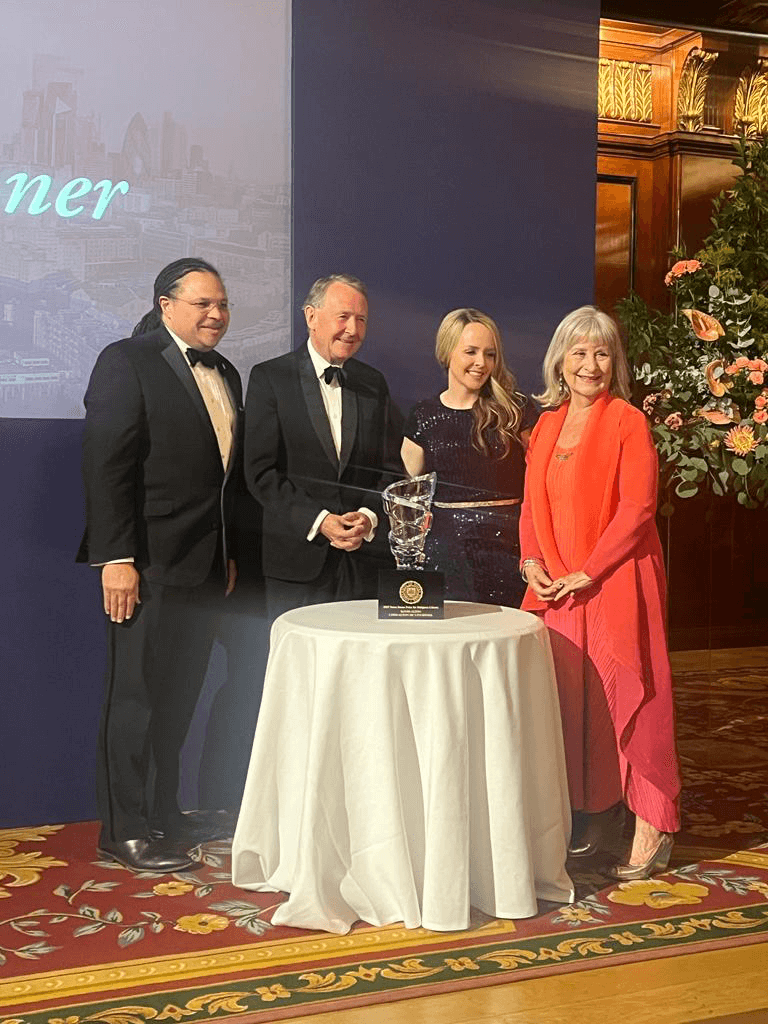

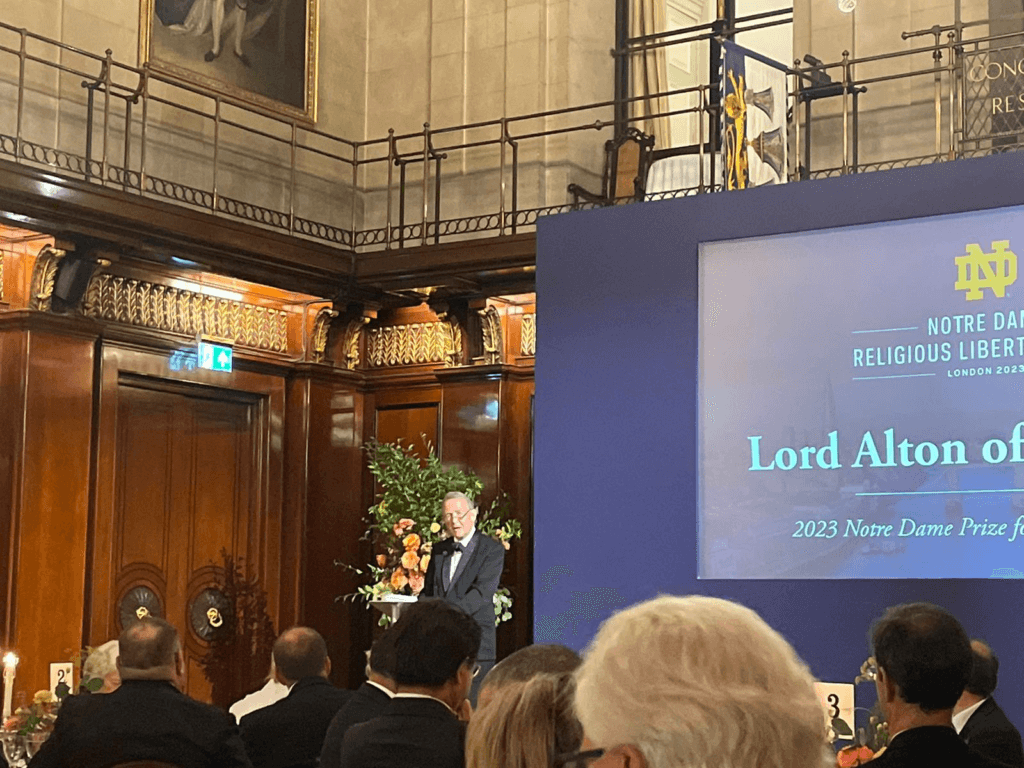

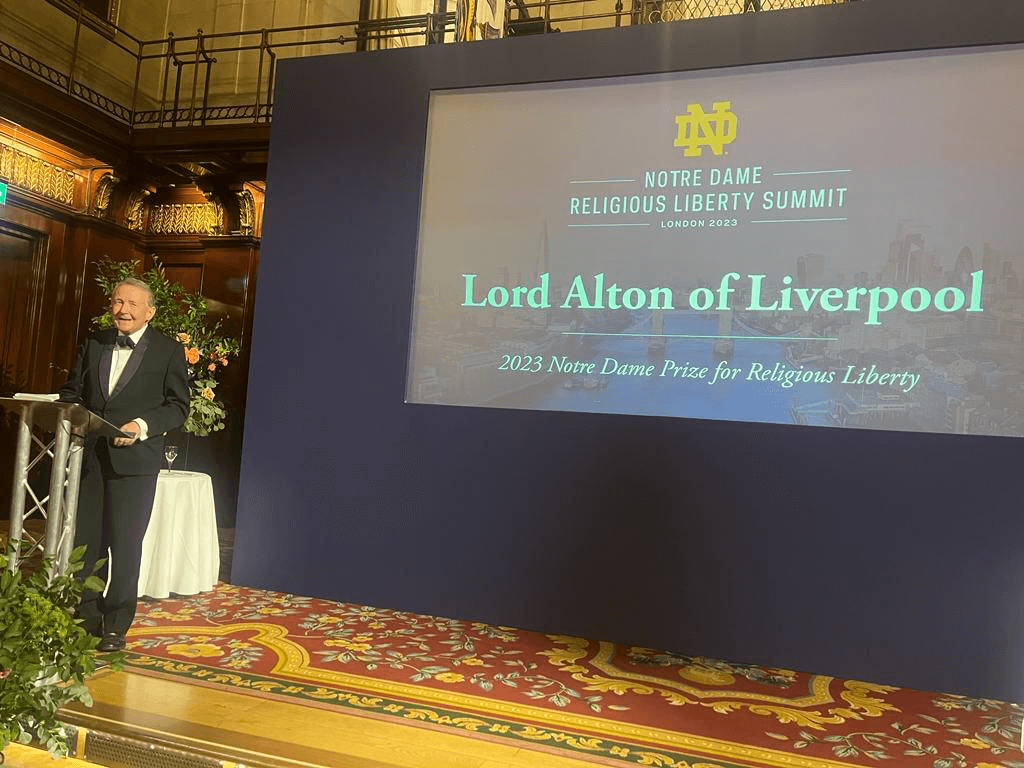

University of Notre Dame: 2023 Notre Dame Prize for Religious Liberty. Acceptance Speech by Professor the Rt.Hon.(David) Lord Alton of Liverpool. Merchant Taylors’ Hall, London. July 13th 2023.

To be awarded the 2023 Notre Dame Prize for Religious Liberty is a tremendous and singular honour. It means a great deal to me – not least because of the respect I have for the previous recipients: Mary Ann Glendon and Nury Turkel.

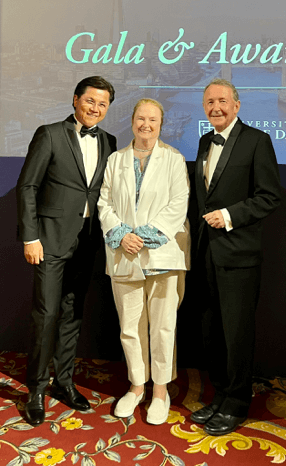

It’s also wonderful to be here with my wife, Lizzie, and my daughter, Marianne and to follow the introductory remarks of my colleague, Baroness (Helena) Kennedy KC.

I also admit to being overwhelmed by the remarkable video that you have made to celebrate this occasion. Tonight is the first time that I have seen it.

Through serving on the Board of Notre Dame Law School’s Religious Liberty Initiative, I have come to know and deeply admire Dean Marcus Cole, Professor Stephanie Barclay and the team in Notre Dame’s outstanding and hugely respected School of Law.

Awards are, of course, a great and generous encouragement to the recipient – but also a spur to do more – but they are also about far more than the individual concerned.

This Award is also for the remarkable people and organisations who have collaborated with me – some of them here tonight – often as volunteers and selflessly giving their time, energy, and expertise in the cause of religious liberty.

Secondly, the award is also about the millions who suffer so grievously because of their religious faith or beliefs.

It is about the outrageous daily breach of Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that guarantees the right to believe, not to believe or to change belief – frequently honoured in its breach with irony of irony, countries like China appointed to the UN Human Rights Council to oversee it.

Last year at least 360 million Christians experienced ‘high levels of persecution and discrimination.‘ Worldwide, 13 Christiansare killed every day because of their faith.

Muslims, Jews, Baha’i, Yazidis, Ahmadis, Hazara, Humanists and many others suffer in societies where no respect is shown for what Jonathan Sacks described as ‘the dignity of difference.’

Religious liberty is a cause that came looking for me rather than the other way round.

Of course, it would have been impossible as a child to have attended a school named for Edmund Campion – or as a Parliamentarian to walk every day through Westminster Hall where he and Thomas More stood trial for their faith, before being executed – without being aware of the price which has been paid for our contemporary religious freedom.

It was a cause that came looking for me in 1979, when as a new MP, I was approached by Danny Smith who was working to free seven Siberian Pentecostal Christians who in 1978 had taken refuge in the American Embassy in Moscow.

It took five years – and interventions from Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, and Pope John Paul II – before, in June 1983, they were allowed to leave the Soviet Union.

Repeatedly, individual cases like these made me see how we take own religious liberties for granted.

But they were also canaries in the mine, warning of acute danger to whole communities

When you ignore discrimination don’t be surprised when it morphs into persecution that when you ignore it what follows are atrocity crimes, crimes against humanity and even genocide will be waiting in the wings.

I also saw the link between persecution and other violations of human rights and global challenges. By way of example consider how many of the 114 million displaced people in the world have become refugees because of religious persecution.

To raise awareness of this foundational concern I realised, very early on, that to be effective we have to form alliances.

Out of the first endeavours in the Soviet Union for the Siberian Seven and Valeri Barinov, Jubilee Campaign in Parliament blossomed, receiving endorsements from all the political leaders and commitments from over 100 MPs of all parties to sponsor individual cases of persecution.

But beyond the alliances, the case for religious liberty is strengthened when we go and see for ourselves; collect the evidence; and not merely rely on press and second hand reports.

Meeting those who have been beaten, tortured, imprisoned, raped, or bereaved never leaves you unchanged. You cant put your hands into someone else’s wounds and remain unaffected.

Wherever I have travelled – from Darfur – from where, earlier today, I heard terrible news of new mass graves – to the Congo, Laos, and Vietnam to Tibet and China, Pakistan, Nepal and India, Burma, Iraq, North Korea and elsewhere – people have repeatedly pleaded that their stories should be documented and known.

Edith Stein, murdered by the Nazis was right ‘Those who remain silent are responsible.’ While another victim of the Nazis, Maximillian Kolbe, could have been speaking to our own times when he said “the deadliest poison of our age is indifference.”

In 1986, the importance of first hand encounter and of speaking out was forcibly brought home to me in Ukraine.

There I met Ivan Gel, the chairman of the Committee for the Defence of the Greek Catholic Church. He had spent seventeen years in prison. Bishop Pavlo Vasylyk had been incarcerated for eighteen years. A young priest had been caught illegally celebrating the liturgies and had just returned from his punishment: six months at Chernobyl clearing radioactive waste, without any protective clothing.

We met people whose family, in the preceding generation had lost their lives in the Holodomor – Stalin’s mass starvation of Ukraine.

I visited churches he had closed 40 years earlier – and where, every day, fresh flowers were defiantly laid at the door to replace the ones removed earlier by Soviet soldiers.

Those people wanted their story known and that is what we did, persuading the BBC to broadcast footage we brought back and a national newspaper to carry an op ed.

Inevitably, since Putin commenced his illegal war in Ukraine, I have often thought about how religious freedom had been so violently repressed and about the courage and bravery of Ukraine’s anti Soviet faith-led pro-democracy movement.

It helps explain why this war is not merely about territory it is about the very soul of a nation.

Later, in Southeast Turkey, I saw first-hand the plight of the Chaldean and Syrianni Christians and the Kurds. I took evidence from the Coptic Christians of Egypt, and had the privilege of meeting His Holiness Pope Shenouda. It is wonderful to see my great personal friend, Archbishop Angaelos, here toninght.

In 2019, with CSW, I returned to the region and in Northern Iraq took first hand accounts of the genocide against the Yazidis and Christians.

Recall that in 2014, ISIS launched a violent attack against the Yazidis in Sinjar.

It then attacked the Christian villages of Nineveh plains, forcing 120,000 people to flee for their lives in the middle of the night. Thousands of men were killed; boys were forced to become child soldiers; and thousands of women and girls were kidnapped for sexual slavery.

Last week, once again, I raised with the UK Government the plight of the 2,763 women and children who are still missing.

This barbarism was inspired by a religious Jihad against a people of a different religion. In their mind it justified murder, imprisonment, enslavement, torture, abduction, exploitation, abuse, forced conversion, marriage, and rape.

In Germany, in the last month, two ISIS women were jailed for keeping Yazidi girls as slaves. There have been convictions for the crime of genocide in Germany while the UK shamefully still fails to recognise it as genocide and as recently as last week opposed my amendment to open a safe and legal route to provide asylum for people of faith or belief.

This is a slow burn genocide which began in 1915 with the Armenians.

In 1933 it continued at Simile, in Iraq, where 6,000 Assyrians were killed.

Simile led Raphael Lemkin, a Jewish Polish lawyer who would see more than 40 of his family murdered in the Holocaust, to begin his work on what would become the Genocide Convention.

Impunity and indifference emboldened Hitler to contemptuously say “who now remembers the Armenians?” as he prepared the way for the Final Solution.

Elsewhere, in places like Vietnam, Laos, Sudan, Pakistan and Burma I have repeatedly seen how indifference and impunity and the failure to remember or to respond to the warning signs leads to unbearable tragedy.

In North Korea, which I have visited four times, the international community has totally failed to act on the findings of the UN’s own Commission of Inquiry which 10 years ago found evidence of crimes against humanity, the targeting of Christians, and calling it ‘a State without parallel.’

My visits led to reports, a book, the formation of an All-Party Parliamentary Group, which I continue to co-chair, and to a young man, Timothy Cho, arriving one day at my university office.

Once again, it is impossible to hear a personal story – Timothy’s story of torture, imprisonment, escape and faith – and to remain indifferent.

Or take China – which has sanctioned me and my colleague Baroness Kennedy. If the CCP’s intention was to shut us up they rather miscalculated. And now Iran has sanctioned me too. I regard it as a badge of honour – the ultimate Award – and one which we should all try to secure.

As well as persecuting people, China, in contravention of the Refugee Convention returns escaping believers to prison camps or death in North Korea. And as we have heard from Nury Turkel, it is responsible for genocide in Xinjiang.

Last year I met Ovalbek Turdakun a Kyrgyz Christian who, with over one million Uyghur Muslims was incarcerated by the CCP. Kept in a windowless cell with twenty-three other inmates he experienced torture – strapped to a ‘tiger chair’ – forced starvation and dubious medical procedures.

In China, think of Tibet’s Buddhists; Xinjiang’s Uyghur Muslims; Chinese Christians – like the bravce young woman journalist, Zhang Zhan, jailed in Wuhan – or Falun Gong practitioners.

Think of the arrest in once free Hong Kong of the venerable Cardinal Joseph Zen and the targeting of Christians lawyers like Martin Lee and Margaret Ng and pro-democracy advocates like the Catholic, Jimmy Lai.

William Wilberforce once famously said that once the facts had been laid before the House of Commons no one could any longer use the excuse that they did not know.

And in a world in which, if anything, there is information overload and a ludicrous disproportionate preoccupation with trivia, we must ensure that these stories don’t disappear into the ether.

The importance of documentation and cataloguing evidence came home to me again last week at a Westminster meeting of the APPG on Freedom of Religion or Belief chaired by my friend Fiona Bruce MP.

Three years ago, she and I promised Rebecca Sharibu when she came to Westminster to describe how her 14-year-old daughter, Leah, had been abducted by Islamists, that we would not be silent about Leah’s fate and the attempts to forcibly convert her, to rape and impregnate her. Now aged twenty she is still held captive.

Earlier this year we held a Hearing with the bishop of Ondo, Bishop Jude Arogundade – in whose diocese 41were left dead on a Pentecost attack on the church of St. Francis Xavier.

Bishop Jude warned British officials not to exhibit religious illiteracy by disingenuously attributing the Jihadist murders of thousands of Nigerians by Boko Haram and ISIS West Africa to climate change.

Such meetings and reports contest false narratives and force the issue of religious freedom up the agenda.

In a world where four out of five people have a religious belief this is hardly a fringe issue – and be even clearer, the denial of religious liberty is a harbinger.

Those countries that deny religious freedom are serial human rights abusers – denying every other human right too. It is a litmus test. Nations that uphold religious freedom uphold other freedoms too. That is why it matters so much.

So how do we change things?

Well, we are changing things – but it requires Herculean and painstaking efforts – like our parliamentary reports about Hazara, Darfur, North Korea, Uyghurs, Rohingya, Tibet and Yazidis. That serious work has led to debates and questions in Parliament, to speeches, to letters and meetings with Ministers. And sometimes to action through our aid programmes – but nowhere near enough.

It is also how you can shoot down the lazy excuse that officials and Ministers ‘did not know.’

But this is the time-honoured way in a democracy – it is what Wilberforce, and the Quaker ladies did as people of faith as they challenged the laws on slavery. They knew you had to change hearts, change minds, change attitudes, change political priorities, to change laws. And the Academy – especially illustrious law schools like Notre Dame – have a significant role to play in this.

Which brings me to my conclusions.

75 years ago this year – after the genocide on the European continent, the Holocaust of the Jewish people – the world promulgated both the Genocide Convention and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and including Article 18 on freedom of religion or belief.

By guaranteeing religious freedom we can increase international justice, stability, and peace. There is also a correlation between the most prosperous happiest societies and those that promote religious freedoms. Religious freedom is not just a nice to have. This too often neglected, orphaned right, needs parents to nurture, uphold and encourage its growth.

The goal must be to achieve religious freedom for everyone, everywhere, whoever they may be.

Why?

Because we each have an inalienable right, flowing from our nature as human beings, to believe in religious truths or, uncoerced, not to do so.

We have the right to freely come together in community with others and to worship in the tradition which we have embraced and with others to create holy spaces and places; to open schools and colleges in which to foster and educate our children.

It is also a duty of those who hold that each person is made in the image and likeness of our Creator to defend the civil, democratic and political rights and upholding of law in respectful societies and especially to defend the voiceless and most vulnerable of God’s children.

The creation of the hugely important Notre Dame Law School Religious Liberty Initiative has given that work renewed definition and impetus. It is a good deed in a sometimes nasty, dangerous, and intolerant world.

It is wonderful that Dean Cole and Professor Barclay have brought this year’s Summit to London. Thank you.

In thanking them and accepting this prestigious Award, I hope the Notre Dame message that freedom of religion or belief is a fundamental liberty – and which must be upheld at every opportunity and in every forum- will be heard loud and clear.

CS Lewis said is impossible to change the beginning of a story, but we can always change the ending – for millions, whose religious freedom is denied let’s resolve to give the story a better ending.

David Alton

Professor the Lord Alton of Liverpool

Independent Crossbench Member of the House of Lords.

www.davidalton.net [email protected] https://twitter.com/DavidAltonHL