Jeremy Hunt, the Foreign Secretary, wrote well on Easter Day about the persecution of Christians. His words were given sombre and stark perspective by the truly shocking carnage in Sri Lanka – but also by further unreported deaths in Nigeria.

In northern Nigeria 17 people were killed after a child dedication service in Nassarawa State and on Good Friday another dozen were killed in Benue. Last night, a further massacre occurred in Gombe state when Boy Scouts marching in an Easter Sunday parade, were attacked with 10 boys killed in Gombe during the Easter procession: https://thenationonlineng.net/breaking-10-boys-killed-in-gombe-during-easter-procession/

If you have any doubt about the scale of what is underway read this article by Mr.Hunt:

__

Foreign Secretary’s Easter Sunday op-ed on Christian persecution

In an op-ed published in the Mail on Sunday, Jeremy Hunt writes that the UK stands in solidarity with persecuted Christians around the world.

GOV.UK Published 21 April 2019 Foreign & Commonwealth Office and The Rt Hon Jeremy Hunt MP

The Easter story begins with persecution but ends in salvation. A man is crucified for his faith, only to rise from the dead and re-join his followers, a miracle that we celebrate today.

But the sombre truth is that millions of Christians will today celebrate Easter while living under a similar shadow of persecution.

Many will be gathering in churches at risk of attack; countless more will have suffered threats or discrimination.

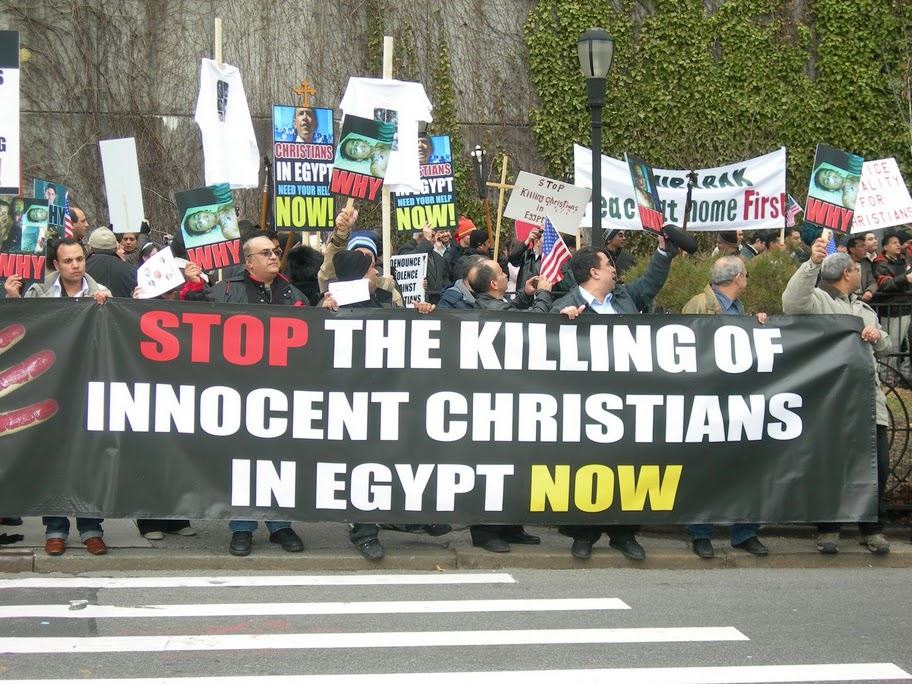

Some Christians will be worshipping at the scene of unspeakable atrocities. St Mark’s Coptic Orthodox Cathedral in Alexandria, Egypt, for example, was the target of a terrorist attack on Palm Sunday in 2017 that killed 17 people.

In the southern Philippines, terrorists planted a bomb in the Cathedral of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, claiming 20 lives during mass on January 27 this year.

The world was rightly shocked by the flames destroying Notre-Dame in Paris last week, a tragedy that touched our common humanity. In too many parts of the world, however, it is the congregations themselves who perish.

As the Prince of Wales wrote on Good Friday, there is something inexpressibly tragic about the innocent being murdered because of their faith.

There is a peculiar wickedness about hate-filled extremism that justifies murder because of the God someone chooses to worship. Of all the people who suffer persecution for their faith, it may surprise some to know that the greatest number are Christian.

In total, about 245 million Christians endure oppression worldwide, according to the campaign group Open Doors. And last year more than 4,000 Christians were killed because of their faith.

In 2015, Christians faced harassment from governments or social groups in 128 nations, according to the Pew Research Centre. By 2016, this had risen to 144. China imposes the ‘highest levels of government restrictions’.

Should religious persecution matter in an increasingly secular world? The truth is that, if a regime tries to control what you believe, it will generally seek to control every other aspect of your life.

Where Christians are persecuted, other human rights are often brutally abused.

Yet the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, passed by the United Nations General Assembly without a single negative vote in 1948, enshrines ‘freedom of thought, conscience and religion’. The declaration makes clear that everyone has a right to the ‘practice, worship and observance’ of their faith.

Britain has always championed freedom of religion or belief for everyone. In my first weeks as Foreign Secretary I prioritised the plight of the Rohingya Muslims, horrifically targeted by the army of Myanmar (formerly Burma.) But I am not convinced that our efforts on behalf of Christians have always measured up to the scale of the issue.

In the Middle East, for example, the survival of Christianity as a living religion now hangs in the balance. A century ago, about 20 per cent of people in the region were Christians; today the figure is below five per cent.

The bitter irony is that Christianity is retreating in the very region of its birth, where its earliest followers worshipped. Anxious not to offend minorities or appear ‘colonialist’ in troublespots around the world, British governments have occasionally taken refuge behind the principle that all religions must be protected.

But this must include Christianity, where those targeted are often extremely poor, female and living in or close to poverty.

We must not allow misguided political correctness to inhibit our response. So I have asked Rt Rev’d Philip Mounstephen, the Anglican Bishop of Truro, to conduct an independent review of the Foreign Office’s efforts to help persecuted Christians and report back to me later this year.

Questions need answering: do we counter oppression based on religion as forcefully as that based on politics or other characteristics? How can we use the considerable influence the UK has in much of the world to better stand up for religious minorities?

I hope he will recommend practical steps for how the Government might strengthen its response. When I moved house last year, I came across a book that I first read when I was about ten. It was called God’s Smuggler by Brother Andrew van der Bijl, a Dutch missionary. At the height of the Cold War, when Christianity was struggling against communist oppression in Central Europe, Brother Andrew began to smuggle Bibles across the Iron Curtain. His book quotes Karl Marx’s famous boast about mobilising the letters of the alphabet to fight ideological battles: ‘Give me 26 lead soldiers and I will conquer the world.’ Brother Andrew noted how ‘this game could be played both ways’. So he set off for Marxist capitals, carrying suitcases packed with Bibles, helping Christians to preserve their faith in defiance of iron-fisted repression.

When I first read God’s Smuggler, it was barely possible to hope that the Iron Curtain would one day fall. So when the Berlin Wall dissolved before our eyes in 1989, it was a wonderful blow for freedom, allowing all the European countries that Brother Andrew had visited to win their liberty.

Yet perhaps this good news has made us complacent about problems elsewhere. Exactly 30 years later, 245 million Christians are still at risk. The evidence suggests that far from easing, the burden of worldwide persecution is actually becoming heavier.

So as we celebrate Easter today we must not be indifferent.

This year I marked Lent by writing 40 letters to 40 persecuted Christians or those campaigning on their behalf. My first letter was to Brother Andrew, now 90, assuring him that the UK stands in solidarity with persecuted Christians around the world: ‘Freedom of religion or belief is a human right enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It must be respected. People from all faiths or none should be free to practise as they wish.’

I will continue to make this case for the millions who suffer as a result of their beliefs and British diplomats will continue to be advocates for all those denied the right to practise their faith.

Many of the recipients of those letters, by dint of the danger they are in, should not be named publicly. But they include men and women, clergy and worshippers, who have been personally targeted by terror organisations, had their churches attacked or been imprisoned by draconian regimes.

Britain is on their side. We care about those who stand up for the right to believe and express one’s faith, and we care about the decent and humane values that inspire those rights.

I hope that one day letters of this kind will not be necessary. Until then, everyone of faith should remember persecuted Christians in our Easter prayers and in our actions.

__

Address by David Alton (Lord Alton of Liverpool):

The Danube Institute Conference on Invisible Victims and Religious Freedom, April 9th 2019, The Reform Club, London

In 1896, at the age of 87, William Ewart Gladstone made his last public speech.

At Liverpool’s Hengler’s Circus, before an audience of 6000, he described what he called the “monstrous crime” of the massacre of 2000 Armenians.

The Hamburger Nachrichten,responded: “For us [Germans] the sound bones of a single Pomeranian [German] grenadier are worth more than the lives of 10,000 Armenians.”

Nineteen years later 1.5 million Armenians were murdered in a genocide still unrecognized as such by the UK, let alone by Turkey.

In 1933, the Jewish writer,Franz Werfel published, The Forty Days of Musa Dagh, a novel about the Armenian genocide.

Werfel’s books were burnt by the Nazis, no doubt to give substance to Hitler’s famous remark:

“Who now remembers the Armenians?”

From the Armenian genocide to Hitler’s concentration camps and the depredations of Stalin’s gulags; from the pestilential nature of persecution, demonisation, scapegoating, and hateful prejudice, in 1948 the international community created a Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

It emerged from warped ideologies that elevated nation and race, insisting on 30 foundational freedoms. Article 18 proclaimed the right to believe, not to believe, to manifest belief, or to change belief:

“Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.”

Understanding how these prized rights have been won; understanding the interaction of religions with one another and with the contemporary secular world; understanding authentic religion, and the forces that threaten it, is more of a foreign affairs imperative than ever before, and, as I shall argue, the resources and determination we put into promoting Article 18 – often described as“an orphaned right” – should reflect that reality.

It is the reality of the surveillance, persecution and incarceration of Christians in North Korea, the demolition of churches in Sudan and China; the unfolding Jihad in Nigeria to outright persecution in Pakistan; and, from the historic attempts to annihilate Christian Armenians, to the contemporary genocide of Christians in Iraq and Syria.

The aim is to stamp out the Christian faith wherever it is found.

The 1948 Declaration’s stated objective was to realise:

“a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations…without distinction to race, sex, language or religion”.

Eleanor Roosevelt, the formidable chairman of the drafting committee, argued that freedom of religion was one of the four essential freedoms of mankind, asserting that freedom of religion was an

“international Magna Carta for all mankind.”

The Hebrew Scriptures are the foundation of such Declarations – and of our belief in universal justice and the rule of law. Today, both are under renewed threat.

Recall the violence last year in the US that led to the deaths of 11 worshippers in a synagogue in Pittsburgh. Reflect that on March 15th nearly 50 Muslims were massacred as they gathered for Friday prayers in Christchurch, New Zealand; remember the 75 Christians murdered in Lahore as they celebrated Easter; mourn the deaths, day after day, in Northern Nigeria which follows the genocide of Christians and Yazidis and other minorities in Iraq and Syria: all tragedies to which hatred of difference can lead.

I have just read Stefan Zweig’s magnificent“The World of Yesterday – Memoirs of a European” published in 1942.

Read Zweig if you doubt how quickly a relatively civilised and humane society, and a seemingly permanent golden age, can be ruthlessly and swiftly destroyed.

His masterful autobiography charts the rise of visceral hatred; how scapegoating and xenophobia, cultivated by populist leaders, can rapidly morph into the hecatombs of the concentration camps.

And consider that, beyond the ugly spectre of Anti-Semitism, appearing in mainstream British politics, in 2019, for the first time since 1945, there are Nazis in the Reichstag; Austria has a coalition government which includes a party whose first leader was as an officer in the SS; Italy has a governing party which is home to fascist throwbacks; while some “yellow vests” in France mighty more appropriately wear black shirts after recently being involved in anti-Semitic abuse of the French philosopher, Alain Finkielkraut; while the far right is capturing seats from Sweden to Spain. And watch with anxiety the coming elections to the European Parliament.

Twenty first century Project Hate can also be seen in the Anti-Semitic memes which accompany digital Nazism – even the live streaming of mass murders courtesy of multi-media outlets.

Other shades of viral hatred – from anti-Semitism to homophobia and overt racism – readily and effortlessly morph from virtual reality into violence.

In his autobiography Zweig wrote that:

“Man was separated by man on the grounds of absurd theories of blood, race and origins” – and so it is again today.

Zweig said:

“The greatest curse brought down on us by technology is that it prevents us from escaping the present even for a brief time. Previous generations could retreat into solitude and seclusion when disaster struck; it was our fate to be aware of everything catastrophic happening anywhere in the world at the hour and the second when it happened.”

And that was the 1940s.

Now it is live streamed and in every living room and on every mobile device within seconds – including pre- arranged broadcast of mass shootings: St. Bartholomew’s Eve Massacres courtesy of Facebook and Google.

ISIS has used social media to express its genocidal intent and, in its recruitment, and propaganda newsletters and videos.

The crucifixion and death of one young man – crucified for wearing a cross – was boastfully posted on the internet.

From the same town, local girls were taken as sex slaves. ISIS returned their body parts to the front door of their parents’ homes with a videotape of them being raped.

The internet is a new tool in the hands of dictatorships and non-state ideologues, intensifying the persecution of minorities.

In China, the State uses digital technology to promote its atheistic opposition to religion but also to collect data against the observant religious adherent whom they see as a threat to their hegemony.

In Russia, subversion of the internet is used to manipulate opinion and to traduce opposition.

And there is a direct correlation between freedom of religion or belief and censorship: Articles 18 and 19 of the UDHR.

There are 44 countries worldwide that control and censor the internet – and the five worst offenders are Saudi Arabia, China, Vietnam, Yemen and Qatar – while North Korea completely bans the internet.

But the Devil doesn’t have to have all the good tunes and just as the Gutenberg revolution of the printed word opened the pages of the Bible the web can also be a place where Faith is shared, and human dignity and rights promoted.

For good or bad it reaches every corner of the Globe and makes ever more urgent the challenge for religious leaders to use it to promote respect for difference and to better understand how their Scriptures and teachings can be rapidly disseminated and distorted to sow division and hatred.

In 1942, in a presentiment of what lay ahead Zweig also remarked:

“We are none of us very proud of our political blindness at that time and we are horrified to see where it has brought us.”

He saw how, in the face of indifference and the desire for a quiet life, the thin veneer that separates civilised values from mob rule very quickly cracked; describing how university professors were forced to scrub streets with their bare hands; devout Jews humiliated in their synagogues; apartments broken into and jewels torn out of the ears of trembling women – calling it “Hitler’s most diabolical triumph.”

Today, persecuted faith-led communities should be natural allies of secularists in combatting neo-Nazis, but deeply intolerant “liberal” voices so despise religion that that they seek to eliminate it from political discourse and the public square. They both need to defend plurality and difference of religion and belief.

Dag Hammarskjold, a Christian, who served Secretary General of the United Nations from 1953-1961 said:

“God does not die on the day when we cease to believe in a personal deity, but we die on the day when our lives cease to be illumined by the steady radiance, renewed daily, of a wonder, the source of which is beyond all reason”

and who said of the UN

“It wasn’t created to take mankind into paradise, but rather, to save humanity from hell.”

With the loss of 100 million lives, hellish ideologies made the twentieth century the bloodiest century in human history. It produced the four great murderers of the 20th century—Mao, Stalin, Hitler and Pol Pot— all united by their hatred of religious faith and liberal democracy.

Now, in the twenty-first century new forms of ideology – some claiming a religious legitimacy – have unleashed new forms of slaughter; and although the UDHR has acquired a normative character within general international law, there has never been universal approbation of Article 18 and the right of freedom of religion or belief remains a contested principle.

Article 18 is proclaimed as a key human right and yet is under attack in almost every corner of the world.

When first adopted by the UN General Assembly, the eight abstentions included the Soviet Union and Saudi Arabia – which argued that there was a conflict with Sharia Law – an issue given sharp focus in Brunei this week.

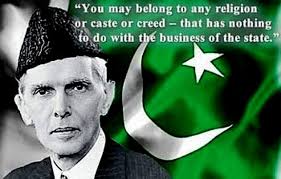

Mohammed Ali Jinnah – Pakistan’s enlightened founding father who insisted that minorities should be given respect and protection in the new country.

In 1948, Jinnah’s Pakistan believed that there was compatibility between Article 18 and Islam – although, as I saw during a visit to Pakistan last November Jinnah’s legacy is often honoured only in its breach.

Note that Open Doors say 80% of the persecution of Christians is the work of people who claim to be religious and most certainly do not subscribe to the principle of “religious freedom for all.”

Repeating history, initial indifference to prejudice and discrimination – made worse by religious illiteracy – rapidly morphs into violence and persecution and then to crimes against humanity and even genocide.

84% of the world population has faith; a third are Christian. But, according to Pew Research Centre 74% of the world’s population live in the countries where there are violations of Article 18 at the hands of Islamists or Marxists.

2.4 billion people live in the Commonwealth —roughly one-third of the world’s population, spanning all six continents—95% of people in the Commonwealth profess a religious belief. Around 70% live with high or very high government restrictions on the right to freedom of religion and belief.

Worldwide, in every country where there are violations, an estimated 250 million Christians are persecuted with 24 of the 37 Anglican provinces in conflict or post-conflict areas.

Although Christians are persecuted in every country where there are violations of Article 18—from Syria and Iraq, to Sudan, Pakistan, China, Eritrea, Nigeria, Egypt, Iran, North Korea, and many other countries — Muslims, and others, suffer too, not least in the Sunni-Shia religious wars so reminiscent of 17th-century Europe.

In Burma, where Buddhists have turned on Muslims, I visited a mosque burnt down the night before, with Muslim villagers driven out of a place where, for generations, they had lived alongside their Buddhist neighbours.

In Rakhine State the Rohingyas have been subjected to appalling brutality along with the Christian Kachin. Now Burma proposes to restrict interfaith marriage and religious conversions.

Think too of the more than 1 million Muslim Uighurs who are detained in re-education camps in President Xi Jinping’s China– so reminiscent of Stalin’s gulags.

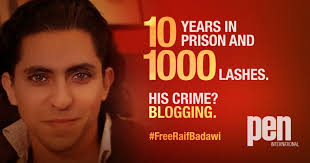

Article 18 is also about the right not to believe – such as Raif Badawi, the Saudi Arabian atheist and blogger sentenced to 1,000 public lashes for publicly expressing his atheism, described by the UN as “a form of cruel and inhuman punishment”; or Alexander Aan, imprisoned in Indonesia for two years after saying he did not believe in God.

And the situation is getting worse.

In 2018, in Parliament, I hosted the launch of the Aid to the Church in Need biannual report on Global Religious Freedom in 196 countries. In 38 it found evidence of significant religious freedom violations and in 18 -including Eritrea, North Korea and Saudi Arabia – it has worsened.

I also attended the launch of the Open Doors 2018 World Watch List. It reports that over 3,000 Christians were killed for their faith in the reporting period; identified the 50 countries where it is most dangerous to be a Christian; and listed the countries where over 200 million Christians experience a “high” level of persecution or worse.

Of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office’s 30 priority countries, listed in its latest Human Rights and Democracy Report, 24 are ranked on the 2018 World Watch List.

In the face of all this ACN says there is “a curtain of indifference.”

It calls to mind the words of that great Pole, St. Maximilian Kolbe, murdered by the Nazis at Auschwitz, who said: “The deadliest poison of our times is indifference.”

Jonathan (Lord) Sacks, our former Chief Rabbi, insists that “Religious freedom is about our common humanity, and we must fight for it if we are not to lose it. This, I believe, is the issue of our time.” But in the face of “one of the crimes against humanity of our time” he is “appalled at the lack of protest it has evoked.”

This indifference is fed by ignorance.

As the BBC’s courageous chief international correspondent, Lyse Doucet, says:

“If you don’t understand religion—including the abuse of religion—it’s becoming ever harder to understand our world.”

In a valiant attempt to understand the relationship between foreign policy and religion the Foreign Secretary has established an Inquiry into persecution of Christians.

Welcome though this is, it will be incapable of radically altering the appalling treatment of Christians unless it has within its mandate DFID’s aid policies and the asylum policies of the Home Office – both currently excluded from the Inquiry’s mandate.

Let me give some examples and describe how indifference to discrimination can lead to persecution and outright genocide.

Discrimination can range from last week’s news that Tajik authorities have implemented a new law barring children from attending religious services and the burning of thousands of calendars with Bible verses to Brunei’s decison to enforce strict Sharia law; to the report today that Iraq’s Parliament has introduced a Bill excluding Christian women from a new Bill recognising the depredations and suffering they experienced at the hands at ISIS.

Religious Discrimination in Eritrea leads to 5,000 people every month a – total of 350,000 people, 10% of the population, fleeing Eritrea. This directly plays into the migration crisis.

In Iran, it led to the arrest and detention of 114 Iranians in a single week for suspected proselytism. It’s illegal to preach or to convert, and converts can spend a decade in prisons like Evin, known as the “black hole of evil”, where torture and abuse are commonplace.

The Iranian Constitution permits worship, but not for converts.

In November last, ITN News, reported on the handfuls of Iranians trying to make it to England in small boats, said that most they spoke to were Christian, some recently converted from Islam.

Ignorance can lead to absurd, unjust and discriminatory asylum decisions – like a recent Home Office refusal of an Iranian convert who was told by an official that Christianity was a religion of violence and if he was a true convert he should “trust God” and go back to Iran – and face the death penalty for apostasy.

Indifference and ignorance also turn a blind eye to aid policies which consolidate discrimination and worse.

Pakistan receives an average of £383,000 in British taxpayers’ money, each and every single day – £2.8 billion over 20 years. Yet freedom of religion and belief is systematically violated.

I have visited and written about the detention centres where thousands of fleeing Pakistani Christians have been incarcerated.

This exodus undermines the prospect of a diverse and respectful society and fails to harness the skills and commitment of ostracised people who are needed to drive down poverty, promote sustainability, and to create a good society.

Propping up a culture of impunity and degraded servility, leads to the murderers of the country’s Christian Minister for Minorities, Shahbaz Bhatti, never being brought to justice; and to an innocent woman, Asia Bibi, given the death sentence and wrongly jailed for nine years for so called “blasphemy.”

Despite the remarkably brave decision of the Supreme Court to affirm her innocence she has still been unable to leave the country, despite acquittal. This is a disgrace.

When I called for her to be offered asylum in the UK, Dr. Taj Hargey, a Muslim Imam based in Oxford, courageously wrote to The Telegraph, demanding that Asia Bibi be given asylum here and spoke of “the deafening silence” from British people of Pakistani origin and of“our collective shame in not preventing her cruel incarceration.”

And this same cruelty leads to children being forced to watch their Christian parents being burnt alive in a kiln.

If a country cannot bring to justice the killer of a Government Minister what chance do these children have of seeing their parents’ murderers brought to justice?

In Pakistan I heard testimonies of abduction, rape, the forced marriage of a nine-year-old, forced conversion, death sentences for so-called blasphemy.

In a left-over from the caste system, menial jobs are reserved for Christians as street sweepers or latrine cleaners.

I recently raised the case of a 13-year-old, excluded from a classroom because he had touched the water supply in that classroom? He was beaten, and his mother was told he had no place in that school because he was only fit for menial and degrading jobs.

Such prejudice is reinforced by school text books funded by Saudi Arabia, and compulsory Quranic teachings in Punjab which demean and stigmatise minorities.

In November I visited some of the “colonies” – ghettos- on the periphery of cities like Islamabad. Here, Pakistan’s Christians live in festering and foul conditions without running water or basic amenities.

Think of South Africa’s apartheid shanty towns – but without the attendant mass movement protests by the Left.

Dirt floors in shacks without running water or electricity. Little education or health provision. Squalid and primitive conditions which are completely off the DFID radar.

No UK funds are targeted specially at these persecuted minorities.

When you question Ministers, they respond by saying,

“We do not collect disaggregated population data on minority groups.”

Well, why not?

These are inevitably the most vulnerable of the vulnerable but, for DFID, ignorance is bliss.

When I asked about child labour from religious minorities in Pakistan I was told: “Child labour is widespread in Pakistan but there is a severe lack of data on the issue” – the data they don’t collect.

But, although they will now undertake a survey, “The information will not be broken down by religious status.”

Nor do they collect data on the girls from minorities who have been raped, forcefully converted and married against their will.

At least 1,000 women belonging to religious minorities, some of them minors, have been abducted, forcibly converted and often married to those very abductors.

From the very poorest sectors of society, they are easy targets for the perpetrators of sexual violence; while the law- enforcement agencies often show little or no interest in helping aggrieved parents to register a police case against the kidnappers.

Even if the case reaches the courts, the abducted are threatened and told that if they tell the court about their kidnappings, their parents and siblings will be killed, forcing them to admit in court that their conversion was voluntary.

In the past few weeks, there have been at least six such cases, which I have drawn to the Government’s attention.

These include a 13-year-old Christian girl, Sadaf Masih, who was kidnapped, forcibly converted and married on 6 February, in Punjab.

On 20 March, two teenaged Hindu girls, Reena, aged 15, and Raveena, aged 13, were similarly kidnapped, forcibly converted and married within a matter of hours, in Sindh.

The kidnappers were married already, with children, but that that did not prevent them from forcibly marrying those girls too. In the worst cases, after sexual and physical abuse, the kidnappers sell the girls into slavery and send them to brothels.

And then there is Pakistan’s corruption.

After government bureaucracy and poor infrastructure, the World Economic Forum identifies corruption as the third-greatest problem for companies doing business in Pakistan.

I recently raised the case of the £41 million Khyber Puktonkhua Education Sector programme, amidst allegations of ghost schools and phantom projects.

Corruption affects all Pakistanis, but it disproportionately affects vulnerable populations—the poor, women, and religious minorities. The Dalit Solidarity Network are right to recommend that DFID should prepare vulnerability mapping tools, inclusion monitoring tools and methods for inclusive response programming.

It is a disgrace that when Christian churches and NGOs seek funds, DFID says no because they say they are “religion blind.”

Paradoxically, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, Pakistan’s illustrious Founder said the country’s minorities must be given equal citizenship – and even insisted that the white in the nation’s flag should represent the country’s minorities.

In that same tradition, Salman Taseer, the Muslim Governor of Punjab, a friend of Shahbaz Bhatti, and also assassinated for speaking out on behalf of Asia Bibi, once said:

“My observation on minorities: A man or nation is judged by how they support those weaker than them not how they lean on those stronger.”

In honouring the memory of Jinnah, Bhatti, and Taseer, Britain’s DFID needs to ensure that some of the £383,000 we pour in to Pakistan every day reaches the persecuted minorities while the Home Office needs to reassess its country classification and admit that discrimination is not a word that does justice to the systematic persecution of Christians in Pakistan.

DFID should reflect on the work of Professor Brian J. Grim into the link between religious freedom and diversity with prosperity.

The poorest basket case countries are those who discriminate or persecute while the most prosperous, happy, and buoyant countries, are those who learn to respect difference and uphold religious freedom.

In 2014 Professor Grim examined economic growth in 173 countries and considered 24 different factors that could impact economic growth.

He found that,

“religious freedom contributes to better economic and business outcomes and that advances in religious freedom”, contribute to,“successful and sustainable enterprises that benefit societies and individuals.”

Where Article 18 is trampled on, the reverse is also true, as a cursory examination of the hobbled economies of countries such as Pakistan, North Korea and Eritrea immediately reveals.

Driving out talented committed minorities deprives a country of ingenuity and skills but also adds to the global migration crisis.

UNHCR says 44,400 people flee their homes every day; that 68.5 million people are displaced worldwide. Yet, like DFID, the Home Office refuse to examine the link between fleeing asylum seekers and religious persecution.

Across Departments, the Government repeatedly says it is“religion blind”but in practice it is religion averse and its policies result in further discrimination and persecution.

By way of example, in the first three months of 2018 out of 1112 Syrian refugees were given the right to enter the UK but not one was a Christian.

Rank discrimination quickly morphs into persecution.

Think of Meriam Ibrahim in Sudan – a young mother of two was charged, and sentenced to death for apostasy and to 100 lashes. Refusing to renounce her faith, and before being freed, she was forced to give birth shackled in a prison cell.

And who can ever forget the execution by ISIS of Egyptian Copts in Libya – after refusing to renounce their faith – or the burning or bombing of more than 50 of Egypt’s churches in Egypt’s Kristallnacht?

In North Korea a United Nations Commission of Inquiry has concluded that around 200,000 people are incarcerated: that it is a “State without parallel”.

Along with assassinations, executions, and torture

“there is an almost complete denial of the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion” and that“Severe punishments are inflicted on people caught practising Christianity.”

One escapee, Hae Woo, a Christian woman gave graphic evidence to a Hearing which I chaired in Parliament of her time inside a camp – where torture and beatings are routine, and where prisoners were so hungry they were reduced to eating rats, snakes, or even searching for grains in cow dung. She said that in such places

“the dignity of human life counted for nothing.”

Recall, too, that on 27 March 2016, Easter Sunday, at least 75 people were killed and over 340 injured in a suicide bombing that hit the main entrance of Gulshan-e-Iqbal Park, one of the largest parks in Lahore, Pakistan. The attack targeted Christians who were celebrating Easter.

We see Christians, like Asia Bibi, sentenced to death for blasphemy; Christians burned in brick ovens with their children forced to watch; girls abducted and enslaved – but the Home Office say it isn’t persecution.

We have seen Yazidis hunted down and trapped on Mount Sinjar, their women raped and turned into sex slaves; but the Government say it isn’t genocide.

From the Philippines to Syria and Iraq we have seen churches, synagogues, mosques and ancient cultural monuments and graves bombed or dynamited with attempts to erase memory, belief, tradition and a whole people’s story.

And now a new tragedy is unfolding in Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country – where indifference to discrimination and a failure by the country’s Government to admit to the ideological nature of the wave of violence – is having devastating consequences.

The Foreign Office say it’s down to squabbles between herders and farmers.

What do you call it when, one year ago, Boko Haram seized a 15-year-old, girl named Leah Sharibu?

They refused to release Leah because she rejected their demand that she renounce her faith and convert to Islam.

Supported with funds and weapons from outside Nigeria, in just one weekend Fulani militia killed more than 200 people, mostly women and children, in sustained attacks on 50 villages.

Localised squabbles or a ruthless ideology?

- Boko Haram say they want to destroy all westerrn ideas, including democracy, and replace Ngieria’s federal constitution with Sharia law.

- Boke Haram have murdered more than 600 Nigerians during the first six months of this year

Last year, I led a parliamentary debate in which I described events over just three days: 140 people were killed in carnage in Benue State.

Later in that month during early morning Mass, militants in Makurdi killed two priests and 17 members of the congregation.

The local chapter of the Christian Association of Nigeria recently revealed that since 2011 herdsmen have destroyed over 500 churches in Benue state alone.

During many of these well-planned attacks by Fulani militia they are often reported by survivors to have shouted “Allahu Akbar.”

A spokesman said:“It is purely a religious jihad in disguise”; another that it is a campaign of ethno-religious cleansing.

Armed with sophisticated weaponry, including AK47s and, in at least one case, a rocket launcher and rocket-propelled grenades, the Fulani militia have murdered more men, women and children in 2015, 2016 and 2017 than even Boko Haram, destroying, overrunning and seizing property and land, and displacing tens of thousands of people.

This is an organised and systematic campaign of targeted attacks.

The Foreign Office must ask from where do this group of nomadic herdsmen get such sophisticated weaponry.

As in Darfur, where I saw the attacks by Janjaweed militias, right across the Sahel, there have often disputes between nomadic herders and farming communities over land, grazing and scarce resources and occasionally there have been retaliatory violence – but the stark asymmetry and escalation of attacks, by well-armed Fulani herders upon predominately Christian farming communities, is fueled by radical Islamist ideology.

The UK and other governments remain in denial about this.

In March, the Revd. Joseph Bature Fidelis, of the Diocese of Maiduguri, in north-east Nigeria said:

“Nigeria today has the highest levels of Islamist terrorist activity in the world…Our country is, so to speak, the future hope of Islamist fundamentalists.”

Archbishop Ignatius Kaigama of Jos, capital of Plateau State says Fulani gunmen exhibit a “new audacity” and the Archbishop of Abuja has warned of “territorial conquest’”and “ethnic cleansing” and said: “The very survival of our nation is at stake.”

In a statement to President Buhari issued by the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of Nigeria, they said:

“Since the President who appointed the Heads of the nation’s Security Agencies has refused to call them to order, even in the face of the chaos and barbarity into which our country has been plunged, we are left with no choice but to conclude that they are acting on a script that he approves of. If the President cannot keep our country safe, then he automatically loses the trust of the citizens. He should no longer continue to preside over the killing fields and mass graveyard that our country has become.”

That is an awesome statement from a Bishops’ Conference, while the respected former army chief of staff and Defence Minister, Lieutenant General Theophilus Y. Danjuma, says the armed forces have not been,“neutral; they collude” in the,“ethnic cleansing in … riverine states”, by Fulani militia. He insisted that villagers must defend themselves because,“depending on the armed forces”, will result in them dying, “one by one. The ethnic cleansing must stop … in all the states of Nigeria; otherwise Somalia will be a child’s play.”

The slaughter of another 130 Christians, within six recent weeks – from the mostly Christian Adara tribe, in the State of Kaduna – goes virtually unremarked and yet it has become the new centre of Islamist extremism.

The Revd. Williams Kaura Abba of the Archdiocese of Kaduna said:

“These latest attacks have reduced many village communities to rubble and raised the level of the humanitarian crisis here to one of extreme gravity,”

adding

“The latest wave of killings began on 10th February, when the Fulani herdsmen murdered 10 Christians, including a pregnant woman, in the village of Ungwar Barde, near Kajuru.”

He described an attack on a five-year-old, during which, failing to kill him with a gun and then a machete, the Fulani finally beat him with sticks in an attack that left him paralysed.

“Not even animals kill people like that…We cannot remain silent in the face of this human slaughter.”

Where is the international indignation; where are the flags at half-mast; where are the protests? In our silence we become complicit in these atrocities.

- The casualties of genocide and crimes against humanity in Sudan

Will Nigeria go the way of Sudan – where attempts to impose a theocratic State led to a civil war, 2 million deaths, partition and, in Darfur, to genocide?

With increasing numbers of deaths, with 1.8 million displaced persons, 5,000 widows, 15,000 orphans, and more than 200 desecrated churches and chapels, it is unsurprising that the Nigerian House of Representatives last July described the herdsmen’s sustained attacks as“Genocide.”

And here is a challenge to teachers in Islamic countries where co-existence is at a premium.

One of the finest texts in the Koran is that “There is no compulsion in religion.”

If that is so, let Article 18 be upheld by good Muslim men and women, along with people of other faiths and none.

In the face of such atrocities as those unfolding in Nigeria religious and political leaders have no right to remain silent as another genocide – comparable to Rwanda, Darfur or Bosnia – plays out its macabre and lethal consequences.

The crime of genocide – the crime above all crimes was defined by the Polish Jewish lawyer, Raphael Lemkin – who had lost 49 of his relatives in the Holocaust. Combined with his own family’s experience, he studied the Armenian Genocide, the massacre of Assyrian Christians at Simele, in Iraq, in 1933.

Raphael Lemkin argued that “international co-operation” was needed,“to liberate mankind from such an odious scourge.”

The 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide states that the 149 signature countries have a moral and legal duty to, “undertake to prevent and to punish.”

But do they?

Think back to the obvious early warning signs of danger in northern Iraq.

Canaries were singing in the mine to warn of impending danger.

On 26 November 2008, I specifically drew attention to,

“the Chaldeans, the Syriacs, the Yazidis and other minorities, whose lives are endangered on the Nineveh plains”. — [Official Report, 26/11/08; col. 1439.];and subsequently, through questions and interventions in Parliament, on 65 occasions.

On 21 April 2016, following mass executions at Mount Sinjar in 2014, I drew attention to,

“accounts of crucifixions, beheadings, systematic rape and mass graves”. — [Official Report, 21/4/16; col. 765.]

and called for UK policies to reflect these realities in our asylum, aid and security policies. I said that too often “Genocide is the crime that day not speak its name.”

We must call it what it is.

This is about the annihilation of peoples and their stories and culture.

Edmund Burke once remarked that,

“Our past is the capital of life.”

Which is why ISIS and their fellow travellers, from Boko Haram to the Taliban, think nothing of defiling Shia mosques, destroying Christian churches, blowing up Afghanistan’s Bamiyan Buddhas and eradicating the Sufi monuments in Mali.

This slow burn genocide, which began with the Armenians, seeks to eliminate humanity’s collective memory, and to eliminate difference and diversity.

And this is not to exaggerate.

In 1914, Christians made up a quarter of the population of the Middle East. Now they are less than 5%.

Last Easter, speaking about this remnant, the Prince of Wales said:

“I have met many who have had to flee for their faith and for their life – or have somehow endured the terrifying consequences of remaining in their country – and I have been so deeply moved, and humbled, by their truly remarkable courage and by their selfless capacity for forgiveness, despite all that they have suffered.”

But now consider what happens after the genocide when these embattled brave people try to return to their homes and communities.

In 2017, Ministers confirmed to me that funding would be available for 80 projects benefiting Yazidis and 171 benefiting Christian communities targeted by the ISIS genocide; £40 million had been earmarked for urgent humanitarian assistance and more than £25 million for UN stabilisation efforts.

On their return to the region, 746,000 Iraqis from these communities were meant to benefit from these Funding Facility for Stabilization projects managed by the United Nations Development Programme.

Over subsequent months, news circulated that the money was not reaching the affected communities.

One of the main reasons for this failure was corruption.

NGOs drew this to the attention of the Government and I attended a meeting with Ministers at which the details of a phantom project were described.

At the end of 2017, in response to a freedom of information request, the Department for International Development refused to provide information describing how these projects were benefiting those minorities and how they were being implemented.

DFID relied on several exceptions, saying that disclosure would or might prejudice relations between the United Kingdom, Iraq and international organisations or courts, and would or might prejudice the prevention or detection of crime. Such information could easily have been disclosed without identifying any details that could jeopardise the various interests cited.

This is public money and taxpayers are entitled to know how it is being spent and who is benefiting.

When comparable concerns about corruption in Iraq were raised with the US Administration, they responded with admirable urgency, transparency and openness, initiating internal inspector-general investigations into the destination of US funds sent to the UNDP which has itself initiated several internal investigations into allegations of corruption.

But not DFID.

So much for restitution but what about our duty to punish those responsible for the genocide in Iraq?

Over many years the Government’s response to the question of genocide determination has been the same: that it is simply for the international judicial systems—which are either inadequate, non-existent or compromised by Security Council vetoes—to make the determination and not for politicians, regardless of the evidence, to support such a determination.

As it stands, the Government do not have any formal mechanism that allows for the consideration and recognition of mass atrocities that meet the threshold of genocide, as defined in article II of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide—the Genocide Convention.

So how can they fulfil their duty to protect, prevent and punish?

The lack of a formal mechanism, whether grounded in law or policy, has been severely criticised in a House of Commons Foreign Affairs Select Committee report published in December 2017.

With Fiona Bruce MP, I have laid the Genocide Determination Bill before Parliament. It seeks to address the lack of a formal mechanism to make the determination of genocide.

Having just commemorated the 70th anniversary of the Genocide Convention, it is high time the Government looked at new approaches to ensure that they are fully equipped to fulfil their obligations under the Convention and to bring those responsible to justice.

Instead of justice, too often we salve our consciences and boast of the money we send but it’s no substitute for real engagement.

Let me conclude.

I think back to a visit I made to a 1,900-year-old Syrian Orthodox community in Tur Abdin, which was literally under siege. On return, I was told by our UK representative that his role was to represent Britain’s commercial and security interests; that religious freedom was a domestic matter in which he did not want to become involved.

Happily, the British public do not share that indifference. A ComRes poll found that nearly half of all British citizens expect their politicians to understand religion and belief.

They understand that you cannot disinvent religion; you can’t order people to leave their faith at home; and properly harnessed they know that religion can be a force for great good in society.

However, it is blindingly obvious that liberal democracy simply does not understand this. At best, the upholding of Article 18 has Cinderella status.

Meanwhile, the classic contours of genocide continue to unfold –“never again all over again” from Nigeria to Burma.

On 42 occasions since 2000, in Parliament, I have raised the plight of Burma’s Christian minorities and on 58 occasions I have raised the plight of the Rohingya Muslims, but we do little or nothing to prevent, protect or punish.

Our best weapon in preventing genocide, persecution and discrimination must surely be the systematic and determined promotion of religious freedom.

Multiple dangers confront humanity today: resurgent nationalism egged on by dictators and autocrats; Islamist and neo-Nazi terrorism; refugees and mass migration; digital technology and cyberwarfare; varying forms of totalitarianism; ideologies hostile to free societies; the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction; the abject failure to resolve conflicts, whether in Yemen, Sudan, Syria or Afghanistan; let alone the blights of natural disasters, famine, poverty and inequality.

But it is increasingly obvious that liberal democracy simply does not understand the power of the forces that oppose it or how best to counter them.

It is a moral outrage that whole swathes of humanity are being murdered, terrorised, victimised, intimidated, deprived of their belongings and driven from their homes, simply because of the way they worship God or practise their faith.

In this new dispensation, as secular liberalism has become increasingly intolerant of religion, old certainties have been displaced while ideology is used to pursue their beliefs in a manner that countenances no alternative view of life.

It is against this backdrop that we must insist on the importance of religious literacy as a competence; encourage Government departments to produce strategies, provide adequate resources, to make religious literacy training available for their staff; and recognise the crossover between freedom of religion and belief and a nation’s prosperity and stability.

And, from the comforts of our fragile liberal democracies, we can also learn a lot – and even be inspired – by the suffering of those denied this foundational freedom.

It was Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the great Protestant theologian executed by the Nazis, said that

“not to speak is to speak, not to act is to act”

Far too often we are guilty of silence and inaction.

I hope that this conference stirs us to speak and to act in the name of religious freedom.

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2019/04/11/can-government-pour-billions-countries-ignore-unspeakable-persecution/

How can the Government pour billions into countries that ignore the unspeakable persecution of Christians?

Islamist students throw footwear toward effigies representing Asia Bibi, a Pakistani Christian woman who was recently released after spending eight years on death row for blasphemy

Surrounded by the crash and roar of Brexit’s tempest, it’s all too easy to forget that for many millions of people around the world to live with some slight constitutional upheaval would be a blissful relief. Across the Middle East, Africa and much of Asia, Christians are subject to incomprehensible persecution and brutality. But comprehension is vital, for this is an issue we in the West shall have to deal with before very long – or risk sitting by complacently while a global religious holocaust happens.

Earlier this week, a hundred journalists, academics, politicians, aid workers, priests and members of the public met in central London for a conference called Invisible Victims. Convened by think tanks The Danube Institute and The New Culture Forum, and Hungary Helps, the world’s only government humanitarian aid programme directly concerned with religious persecution, the point was not only to tell people about the atrocities occurring under our very noses but to issue a call to arms.

Lord Alton of Liverpool told the audience how Article 18 of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights, which guarantees the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion, is being ignored in every corner of the world, while liberal voices remain strangely silent. Religious discrimination against Christians in Eritrea leads to 350,000 people a year fleeing the country, contributing directly to the migrant crisis.

One of the litany of unbearable stories heard throughout the day, which ought to shame Penny Mordaunt and the civil servants at the Department for International Development (DfID), was the story of the two Christian Pakistani children, forced to watch as their parents were burnt alive in a kiln.

Lord Alton told us of the multiple cases of kidnap, forced conversion and forced marriage of teenage girls in Pakistan he has raised with DfID. ‘Discrimination is not a word that does justice to the systematic persecution of Christians in Pakistan,’ he said, mentioning the £383,000 a day in British aid Pakistan receives. ‘Instead of justice, we too often salve our consciences and boast of the money we send.’

This is utterly shameful, yet far from unique. Of the top twenty beneficiaries of UK aid, nine – Afghanistan, Somalia, Pakistan, Sudan, Yemen, Syrian, Nigeria, Iraq and Burma – are in Open Doors’ list of the twenty worst countries for religious persecution. They receive between them £2,036 million a year, 54 per cent of the total for the top twenty recipients.

It should be a stipulation of aid being granted that in future the governments of those countries where Christians are known to be persecuted demonstrate stringent measures to eradicate the problem. The UK should not be giving financial assistance of any sort to nations where religious persecution goes unpunished – still less to those where governing parties condone anti-Christian action.

As we heard repeatedly from Parliamentarians, the UK Government refuses to accept the Islamist nature of attacks on Christians in Nigeria. The Foreign Office refuses to accept that Fulani herdsmen armed with AK-47s attacking unarmed Christian farmers do so as jihadists, describing it as ‘tit-for-tat clashes’.

The media and governing classes of our country refuse to accept that persecution of Christians is endemic to large parts of the world as a direct result of militant Islamism, preferring to hide behind the condescending notion it is all just a little local difficulty and will stop once the natives have had a scrap.

In part this is due, as Damian Thompson of the Catholic Herald, said, to the ‘extraordinary indifference to the importance of religion as a subject [for coverage], even among practising Christians. It’s as though they’re embarrassed to write about the subject.’

It is also, and more perniciously, an aspect of misplaced post-colonial guilt, as though those Christians who are Christian because of the work done by Victorian missionaries deserve the persecution they suffer.

While this remains a fringe issue in public debate, governments and major media agencies will have no impetus to act.

Into what moral turpitude will we have fallen if we allow this persecution to continue unchecked, if we turn our faces against millions of people crying out for help we could give so easily? Though the victims are for the most part Christian – a major exception being the Uighur Muslims of China – this is not a problem to which Christians alone must respond. The onus is on every one of us who considers him or herself a moral being to stand up and say: enough.

David Oldroyd-Bolt is a writer, cultural commentator and communications consultant. He tweets as @david_oldbolt.