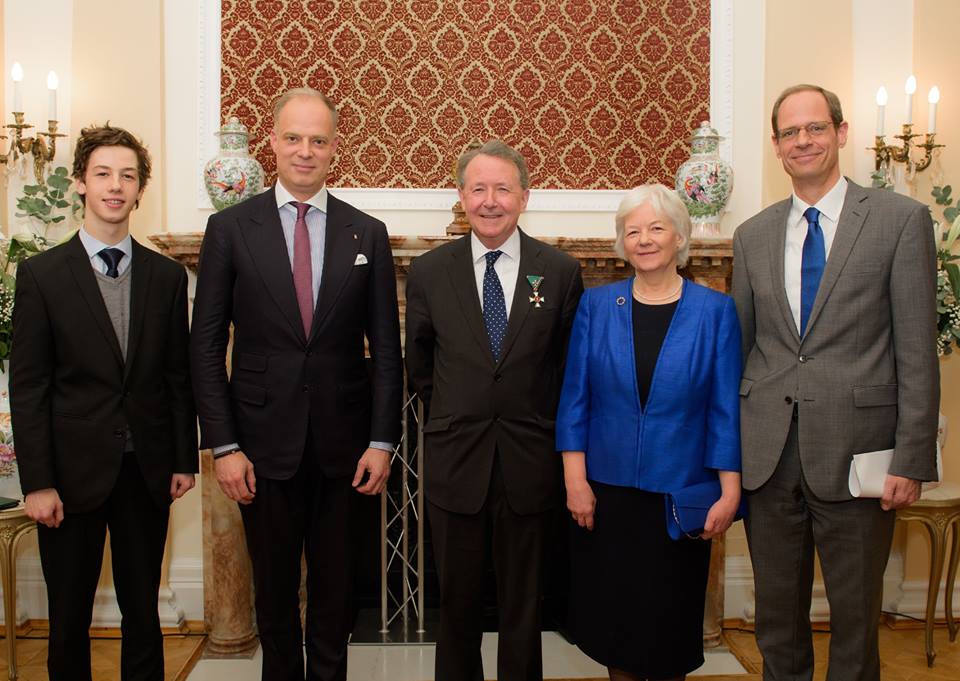

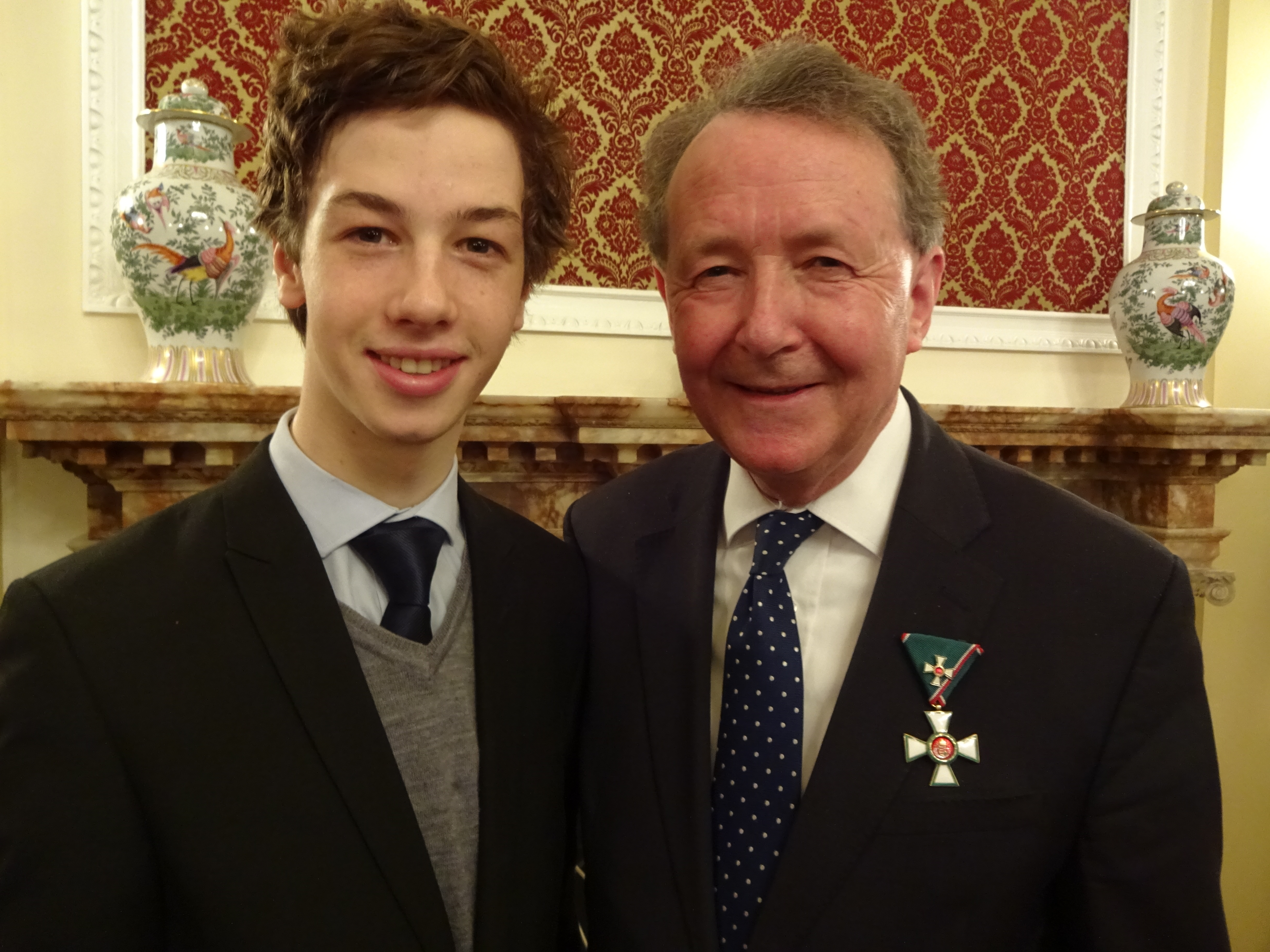

Lord Alton Awarded Hungarian Order Of Merit January 18th 2017

James Alton, Ambassador Kristóf Szalay-Bobrovniczky, David and Elizabeth Alton, former Ambassador Péter Szabadhegy

Response

Lord Alton of Liverpool:

On the occasion of his investiture by the Hungarian Government

with the Commander’s Cross of the Order of Merit of Hungary

Ambassador Kristóf Szalay-Bobrovniczky, My Lords, Members of the House of Commons, Distinguished Guests and Friends.

My first duty on this wonderful occasion is to thank Mr János Áder, President of the Republic of Hungary for conferring on me the Commander’s Cross of the Order of Merit of Hungary; to warmly thank his Excellency for conducting the investiture on behalf of the President; and to thank each of you for being here to share this occasion with me.

Tonight has its origins in the year 1170 when King Henry II reputedly in a rage of hot temper, is said to have shouted “Will no one rid me of this troublesome priest?”

On 29th of December of that year four knights rode to Canterbury and murdered Thomas Becket.

Within 20 years of his death, 15 biographies were written about him – and even in our own times new biographies continue to be published. Canonised by the Pope his shrine became the most popular in England: the destination of Chaucer’s pilgrims and many others.

Becket’s name – and murder in the cathedral – became synonymous with the never ending struggle between States and temporal leaders and those who want freedom to follow their religious beliefs.

This evening I want to briefly reflect on what Becket’s struggle has to say to our two nations today.

On November 23rd, 2016, on Red Wednesday, we lit up buildings all over the country in red, including the Houses of Parliament, to commemorate the 5.3 billion people, 76% of the world’s population, who live in countries with high or very high levels of restrictions on freedom of religion or belief. Red Wednesday coincided with the launch of this year’s Aid to the Church In Need “Religious Freedom in the World” report, which I chaired.

From Bangladesh, where atheists are murdered with impunity; to Saudi Arabia where churches are banned and converts are criminalised; to Burma, where Muslim Rohingya are denied citizenship; to Iran where Baha’i are executed; to China, where bishops are imprisoned and churches demolished; to countries like Syria, Iraq, Nigeria, Pakistan, Sudan and North Korea, where believers are subjected to genocide, crimes against humanity, persecution or discrimination; lives are literally soaked in blood, as contemporary Beckets die for their faith.

Red Wednesday was a chance to show solidarity with them, to demonstrate that their suffering is not forgotten; a chance to shine a light on global suffering; and on the significant driver it has become for the displacement of many of the world’s 65.3 million refugees who have had to flee their homes, because of terror and violence against religious minorities.

Conversely, there is also a direct correlation between peace, stability, prosperity and societies that insist on religious freedom – countries like North Korea and Eritrea please note.

Hungary’s own story testifies to this.

In 1948 Communists dissolved most of Hungary’s religious Orders, confiscating their schools. 4000 Catholic associations and clubs, were forcibly disbanded. Clergy were imprisoned or prosecuted for resistance, most notably Cardinal Jozsef Mindszenty, Primate of the Catholic Church in Hungary and Archbishop of Esztergom. In 1950 alone around 2,500 monks and nuns were deported and the Communists banned sixty-four of sixty-eight functioning religious newspapers and journals.

For five decades Cardinal Mindszenty personified uncompromising opposition to fascism and communism in Hungary. Imprisoned by the pro-Nazi Arrow Cross during World War II he then spoke out against communism, was subject to a show trial, imprisoned, tortured and given a life sentence.

Freed in 1956, in the Hungarian Revolution, he was given asylum in the US Embassy in Budapest where he lived for the next 15 years. Wishing to be free of this troublesome priest he was allowed to leave in 1971 and died in 1975 died in exile in Vienna. Recall too the role of the reformed churches in Hungary during the 1956 uprising – and its Statement of Faith composed the previous year, following the example of Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the German Confessing Church which had defied Hitler.

Its leaders told the Communist authorities “we are ready to suffer reprisals for obeying Christ’s command only. We regard our obedience to Christ as imperative for all of us and doubly imperative for our pastors.” ‘They quoted Acts 5: “We must obey God rather than men!’ Many were arrested or detained, and they included a young Hungarian Christian, Geza Nemeth.

By the 1970s, Geza Nemeth, was a dissenting Pastor, who saw his church destroyed by the authorities and he was deprived of his ministry. His humiliation and trials proved to be a blessing in disguise. Forced to travel, selling art, he was invited by local pastors into Reformed, Free Church, and Roman Catholic churches. His Christian witness deeply impressed his audiences, especially young people, and many of them came to a living faith, one which wasn’t frightened to challenge an overbearing totalitarian State.

In 1985, while serving as Liberal Chief Whip in the Commons, a young Oxford graduate, David Campanale, came to work for me. He introduced me to a fellow Oxford student: Zsolt Németh, Geza Nemeth’s son.

Years later I travelled to Budapest with David and Zsolt, stayed at Pastor Nemeth’s home, and we travelled to Hungarian Romania where Zsolt’s father gave great help to the ethnic Hungarian refugees during Nicolae Ceausescu’s communist dictatorship. Zsolt, with Victor Orban, whom I also met, was a founder of the post-Communist Fidesz Party – going on to become the country’s Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, and Victor, of course, became Prime Minister.

From the earliest times, Hungarian reformists and Fidesz leadership found a welcome in the UK, whether at Oxford or through their political links. Never doubt, then, the wisdom of providing support and educational opportunities to those challenging totalitarianism – for today’s dissidents may be tomorrow’s leaders. And, in understanding them, never forget the fires though which they came.

While travelling with Zsolt and David we heard first-hand accounts of grievous suffering and amazing courage. In Cluj we met Doina Cornea – a remarkable Greek Catholic dissident and human rights campaigner. We talked with Laszlo Tokes, the pastor and hero of Temesvar, now a Member of the European Parliament, and in Alba Iulia met Cardinal Alexandru Todea, who was secretly consecrated a bishop and endured 16 years in prison and 27 years under house arrest. He told his communist jailers: “You have no power to fight me. I risk nothing, because I have nothing to lose.”

On other visits to the Soviet Union, Poland, the Ukraine, Albania, China and North Korea I met many more who believed their faith was worth dying for. It is wonderful that one young man, Timothy, is here tonight.

Timothy was tortured in North Korea, and this year became the first North Korean to graduate at a British university. He is now being helped in his Masters Course studies in the UK by the Hungarian Government. I salute that and their decision, in September, to establish a new department to aid persecuted Christians. Zoltan Balog, Hungary’s Minister for Human Resources, whose ministry will oversee the new department, says that “[We] will do everything in our power to improve the circumstances of Christians living in the Middle Eastern region.”

For the sake of Christians, Yezidis and others, facing genocide in Syria and Iraq, I wish other Governments, including our own, would follow the example of the Hungarian Government.

We who have so many privileges and freedom but indifferently allow the erosion of Judaeo-Christian beliefs in our own country – witness for instance the sacking of two midwives because they would not perform an abortion – may remain silent because, unlike Cardinal Todea, we have too much to lose, preferring to live a quiet life. B

ecket was right when he said “remember the storms that were weathered… the crown that came with those sufferings and which gave new radiance to faith.”

That we should never forget the sacrifices of those who have weathered storms is one of the reasons why I immediately responded when Ambassador Péter Szabadhegy suggested that the relics of St. Thomas Becket should be brought to the United Kingdom.

It was an opportunity to reflect on our own story, on who we are, and the price at which our privileges and freedoms have been won. In thanking Peter, and Anton de Piro who, on behalf of the Christian Heritage Centre charity that I chair, worked selflessly may I also pay tribute to the outstanding Embassy staff who organising the Becket events.

I was deeply moved and challenged when the martyr’s relics returned to England after 800 years in Esztergom – an ancient capital of Hungary and one of Hungary’s oldest cities, which was besieged, occupied and liberated during Ottoman Islamic conquests in Europe. It is the Mother Church of Hungary and Cardinal Péter Erdő, Primate of Hungary, with President János Áder, accompanied the relics to London.

Beyond what the relics say to us about Becket himself and the fight to uphold religious freedom; they also have a great deal to say to us about friendship.

When Becket was murdered at Canterbury, while Vespers were being sung, it was the bloody climax of a long feud and illustrates how even close friends can become estranged and see they friendship destroyed. The consequences can be truly shocking.

But the relics tell a positive story of friendship, too.

While Becket had been a student in Paris he became a close friend of a young Hungarian, Lukacs Banffy. Lukacs went on to become Cardinal archbishop of Esztergom and when Becket was martyred he founded a church named after Thomas and it is believed that that Queen Margaret of France, and later of Hungary, was then instrumental in bringing the relics to Hungary 800 years ago.

In Lancashire, at Stonyhurst, we too have a relic which was secreted after Henry VIII’s destruction of Becket’s shrine and his persecution of Catholics. Our Becket relic is an inspiration to our Christian Heritage Centre which has now seen more than £2.5 million spent on its first two phases and a further £2.7 million raised towards the £4 million we need to open Theodore House, named after a Syrian Christian who was also an Archbishop of Canterbury – and where a next generation of Banffys and Beckets will be formed.

Let me end. Dietrich Bonhoeffer once said that “Not to speak is to speak, not to act is to act” – and, like Becket, he paid the ultimate price. Whether it is standing against a Henry II or Henry VIII, against Communism, Nazism, radical Islam, or a totalitarianism that creeps up in carpet slippers, we need a new generation that speaks and acts on the basis of the 2000 years of Judaeo-Christian principles which have provided Europe with sure foundations.

Ambassador, you have reminded us that “where heroes are not forgotten, new hopes are born.” You have told us that “when nation speaks to nation, heart must also speak to heart.”

The French say that to encourage others you must shoot a few admirals. Clearly, Hungarians provide encouragement in a more humane and civilised way. The Commander’s Cross is a singular honour and a great encouragement to do more – I am deeply honoured to receive it.