Tolkien: Faith and Fiction

click here to view the power point presentation which accompanies the following lecture:

faith-in-the-work-of-tolkien – view full powerpoint presentation accompanying the lecture

tolkien-faith-and-fiction-liverpool-2016 Text

Liverpool Hope University, November 2016.

David Alton, Lord Alton of Liverpool.

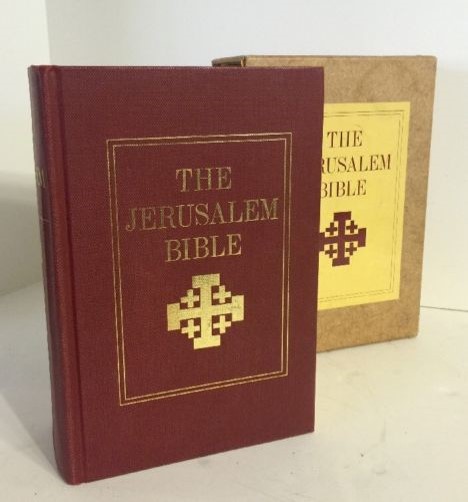

This year, 2016, marks 50 years since, in 1966, the English edition of the Jerusalem Bible was published.

The translation was undertaken here at Hope, at what was Christ’s College, my old College. The work was led by the brilliant scripture scholar, Fr.Alexander Jones.

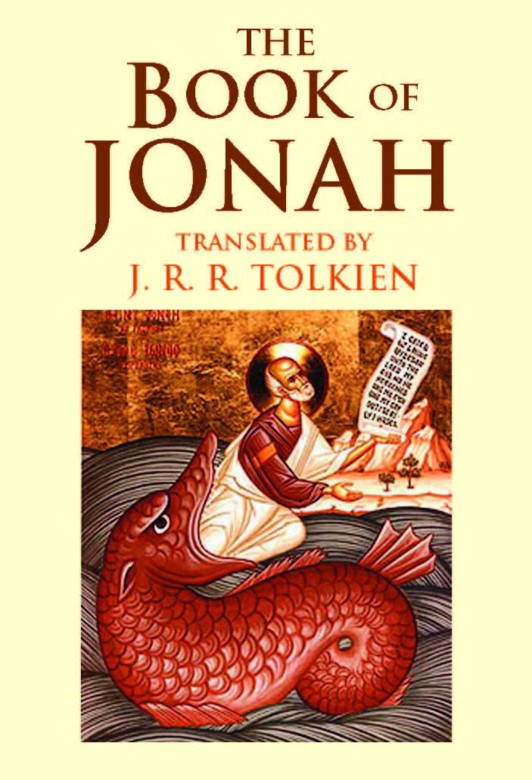

J.R.R.Tolkien was one of those who contributed to the translation and it includes his translation of the Book of Jonah and an acknowledgement of his role.

Fr.Henry Wansborough OSB said “It was the first translation of the whole Bible into modern English to appear. It was an iconic presentation of the best of Catholic biblical scholarship in the previous half century.”

When, in 1969, I came here as a student, my first purchase was a still greatly prized and now well-worn copy of the JB, the Jerusalem Bible.

Jonah is among the books of the prophets – and once given the Word they are compelled to speak it: Amos cries “The Lord Yahweh speaks, who can refuse to prophesy?”

And of Jonah and the other prophets, Alexander Jones said “At a point in each of their lives each received an irresistible divine call and was chosen as God’s envoy. The price of attempting to elude this vocation is stated in the early part of the story of Jonah.”

He says Jonah is unlike the other prophetic books because “this short work is entirely narrative. It tells the story of a disobedient prophet who first struggles to evade his divine mission and then complains to God that his mission has, against his expectations, been successful.”

I can’t help speculating that Alexander Jones may have had another reluctant hero in his mind when he asked the creator of home-loving risk-averse reluctant-hero Hobbits to collaborate in the translation of the Book of Jonah.

And like many aspects of Tolkien’s work, Fr.Jones reminds us that the story of Jonah which he describes as a droll adventure, taking us from the “the belly of Sheol” – to the city of Nineveh, is precisely that – a story, not history; a “didactic work” that is “intended to amuse and instruct” and which “proclaims an astonishingly broadminded catholicity.”

God is merciful to all, even to the rebellious Jonah. The lessons of mercy, humility and repentance are given to the Chosen People at the hands of their sworn enemies.

You can see why Tolkien would have been entirely at home with this Book and these themes.

The Book of Jonah concludes with God explaining, with great love mixed with some gentle irony, that He will not only be merciful to Jonah, the reluctant prophet, but also to the repentant Ninevehites and their little children “who cannot tell their right hand from their left,” and proclaiming still further, His love of all His Creation “to say nothing of all the animals.”

The story of Jonah is also a dramatic prefiguring of the only story which really matters: Jonah’s three days in the belly of the great fish prepares us for Christ’s three days in the tomb. Fr.Jones says that at this moment in the Old Testament “We are on the threshold of the Gospel.”

Tolkien would describe such a turn of events in a story as a “eucatastrophe,” – a word to which I will return at the conclusion of my remarks.

“I coined the word ‘eucatastrophe’: the sudden happy turn in a story which pierces you with a joy that brings tears (which I argued it is the highest function of fairy-stories to produce). And I was there led to the view that it produces its peculiar effect because it is a sudden glimpse of Truth.”

For Tolkien the greatest ‘eucatastrophe’ of human history was the resurrection of Christ from the tomb. So its preconfiguration in the biblical Book of Jonah is a pretty good place to start when considering Tolkien, Faith and Fiction.

Tolkien, himself, said that The Lord of the Rings was “a fundamentally religious and Catholic work”. What did he mean by that and what clues are there in the characters, the tales within the tale, and within the plot itself?

Let me divide my remarks into 3 parts:

- How Tolkien’s experiences shaped his beliefs;

- What Tolkien tells us himself; and

- How faith shapes the characters, and the story lines.

- 1. How Tolkien’s experiences shaped his beliefs.

Born in Bloemfontein, in the Orange Free State, in 1892, his father died in 1896, and his mother, Mabel Suffield, returned to England, to the Midlands. Her conversion to Catholicism, in 1900, led to her rejection by her mixed Baptist, Unitarian and Anglican relatives. She was reduced to poverty.

Struggling as a widow, and shunned by her family, Mabel sought solace and help from the Catholic community of the Birmingham Oratory.

The Birmingham Oratory – whose full title is the Congregation of the Oratory of St.Philip Neri and is located in the Edgbaston district of Birmingham, was founded in 1849 by Blessed John Henry Newman, who died in 1890, two years before Tolkien’s birth.

It was the first house of that Congregation in England and Newman, a celebrated Catholic convert, had been given permission by Pope Pius IX to establish a community of Oratorians in England and Newman lived a secluded life there for the best part of four decades.

Newman had died only ten years before Tolkien, in his childhood, spent nine years as a parishioner of St. Philip’s and attended the parish school before winning his scholarship to the Birmingham’s King Edward’s school.

In 1904, after the death of his mother at the age of 34, a death “hastened by the persecution of her faith”, as Tolkien remarked in 1941, he was shunted between relatives until a lodging was found for him by an Oratorian priest, Father Francis Morgan, who was his legal guardian.

In 1963 Tolkien wrote about the effect that these experiences and formative years had on him: “I witnessed (half comprehending) the heroic sufferings and early death in extreme poverty of my mother who brought me into the Church.”

His great closeness and devotion to the Theotokos – Mary, the Mother of God – began with the premature death of his own mother. He said that Mary “refined so much of our gross manly natures and emotions as well as warming and colouring our hard, bitter, religion.”

Of Fr.Francis he wrote: “I first learnt charity and forgiveness from him” and he said that he taught him the story of his Faith “piercing even the ‘liberal’ darkness out of which I came, knowing more about ‘Bloody Mary’ than the Mother of Jesus – who was never mentioned except as an object of wicked worship by the Romanists.”

The backdrop to Tolkien’s childhood was rejection and sectarianism but his connection with the Oratory gave him a love of the mystery of the sacraments but it also taught him to honour Scripture and tradition along with the teaching authority of the Church, grounded in the apostolic succession. He believed that Christ was, in the words of Newman’s hymn, Praise to the Holiest in the Heights, the Second Adam who to the rescue had come – sanctifying history and saving each of us.

And can we not see in Tolkien’s fiction, and the quest and mission of the Hobbit, something of Newman’s belief that:

“God has created me to do Him some definite service. He has committed some work to me which He has not committed to another. I have my mission. ..I am a link in a chain, a bond of connection between persons….”

Newman had been the most influential Catholic in the English speaking world during the nineteenth century and his Apologia and love of St.Augustine were the scaffold on which Tolkien’ s faith was hung.

Newman had insisted that “To live is to change, and to be perfect is to have changed often”; that “We are answerable for what we choose to believe.” that “Nothing would be done at all if one waited until one could do it so well that no one could find fault with it”; that Growth is the only evidence of life.” That “fear not that thy life shall come to an end, but rather fear that it shall never have a beginning” and that “The love of our private friends is the only preparatory exercise for the love of all men”.

The young Tolkien would have heard a great deal about Newman and studied him carefully – not least his famous treatise on the purpose of a university – the world in which he would spend his professional life:

“The University’s…. function is intellectual culture… It educates the intellect to reason well in all matters, to reach out towards truth, and to grasp it.”

While at King Edward’s, Tolkien and three friends, Rob Gilson, Geoffrey Smith and Christopher Wiseman formed a secret society which they called the “T.C.B.S.” – the acronym meaning “Tea Club and Barrovian Society”. The name had its origins in their fondness for drinking tea at the nearby Barrow’s Stores and, illicitly, in the library of their school.

From King Edward’s, Tolkien won an exhibition to Exeter College, Oxford in 1910, and graduated with First Class Honours in 1915.

He showed early promise as a philologist and gifted linguist with a remarkable facility to decode ancient languages. He used these gifts in scholarship and in prose and the study of legend, folklore and poetry.

In 1914 he read a poem by the Anglo-Saxon Christian poet, Cynewulf. He wrote later about how two lines of the poem Crist (Christ) remained with him:

Eala Earendel engla beorhtast

Ofer middangeard monnum sended!

Hail Earendel, brightest of angels,

Above the middle-earth sent unto men!

The friends of the T.C.B.S stayed in touch after leaving school, and in that same year, 1914, met at Wiseman’s London home for a “Council.”

In many respects the T.C.B.S foreshadowed the Kolbitar (Coalbiters) which Tolkien would form at Oxford in 1925 – and which was devoted to reading Icelandic sagas. Lewis attended their meetings and, in the 1930s, from this fellowship of friends would finally emerge the Inklings – more of which, later.

In Birmingham Tolkien had met Edith Bratt, with whom he fell in love; he also commenced his practice of daily Mass attendance, which he continued throughout his life.

Fr.Morgan counselled him not to rush into marriage but, having been commissioned into the Lancashire Fusiliers, he feared that he might be killed. He and Edith, who was received into the Catholic Church, married in 1916.

After seeing action in the Somme, acting as Battalion Signalling Officer – and, having contracted trench fever, Tolkien spent the rest of the war as an invalid.

The news from his friends in the TCBS was bleak. On July 15, 1916, Geoffrey Smith wrote to tell Tolkien of Rob Gilson’s death: My Dear John Ronald, I saw in the paper this morning that Rob has been killed. I am safe but what does that matter? Do please stick to me, you and Christopher. I am very tired and most frightfully depressed at this worst news. Now one realises in despair what the T.C.B.S. really was. O my dear John Ronald whatever are we going to do? Yours ever. G. B. S.

Five months later, Christopher Wiseman wrote to Tolkien to say that Smith had died in a mission. Just before seeing this final action Smith wrote these words to Tolkien:

“My chief consolation is that if I am scuppered tonight – I am off on duty in a few minutes – there will still be left a member of the great T.C.B.S. to voice what I dreamed and what we all agreed upon. For the death of one of its members cannot, I am determined, dissolve the T.C.B.S. Death can make us loathsome and helpless as individuals, but it cannot put an end to the immortal four! A discovery I am going to communicate to Rob before I go off tonight. And do you write it also to Christopher. May God bless you my dear John Ronald and may you say things I have tried to say long after I am not there to say them if such be my lot.” – Yours ever, G.B.S.

Like C.S.Lewis, and so many of his generation, Tolkien was deeply affected by World War One and the death of his friends.

As his closest intimates were cut down, it put an end to the circle of friends and, challenged by Smith’s haunting words: “may you say things I have tried to say long after I am not there to say them”, Tolkien began to write his epic mythology on a notebook entitled “The Book of Lost Tales.” The tales would come to be known as “The Silmarillion.”

The hobbits entered his imagination in 1929, while marking examination papers, when Tolkien started to jot down some words for a story to read to his children – of whom there were now four: “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit”. Tolkien would later say of himself: “I am in fact a Hobbit, in all but size…I like gardens, trees…I smoke a pipe, and like good plain food (unrefrigerated), but detest French cooking…”

Tolkien was like his hobbits, dreaming of eggs and bacon.

Like the Book of Jonah, Tolkien’s tales have an extraordinary catholicity – an equal appeal to the Deist, atheist, agnostic or Pagan reader, of all ages and backgrounds. Like Jonah it is not about historical truth – although Middle Earth feels like a place that once existed – it is a story which provides sign posts to the ultimate Truth as well as sign posts about how we should relate to one another, about friendship, courage, honesty, integrity and the seemingly endless battles that we are each destined to fight on our journeys; how the ring is representative of tyrannical power, pride, temptation, addiction and sin. In this sense The Lord of the Rings is a “true” story.

It resonates with Tolkien’s own experiences and the time in which it was written – although he always insisted it was not allegory but rather might have applicability to those times and to all times.

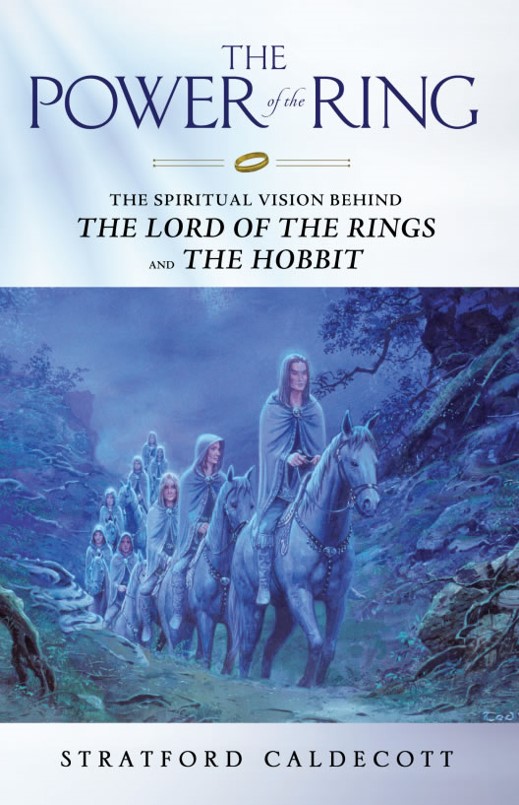

In his wonderful book, “The Power of the Ring” the late Stratford Caldecott, said of Tolkien’s work “at an even deeper level it is about the reality and value of beauty…the homely beauty of firelight and good cheer, the rich natural beauty of tree and forest, the awesome majesty of mountains, the charm of babbling stream, the high and remote glimmer of the stars…recalling the mystery that lies beyond the beauties of this world, and awaken a longing in the human heart that will never be quite content in Middle-earth.”

By contrast, Edmund Wilson described The Lord of the Rings as “juvenile trash” while that angry atheist, Philip Pullman, author of “His Dark Materials” has called The Lord of the Rings “trivial”:

“Tolkien was a Catholic, for whom the basic issues of life were not in question… So nowhere in ‘The Lord of the Rings’ is there a moment’s doubt about those big questions. No-one is in any doubt about what’s good or bad; everyone knows where the good is, and what to do about the bad. Enormous as it is, TLOTR is consequently trivial”

When the first volume of The Lord of the Rings was published Tolkien knew that he was leaving himself open to inevitable scorn, writing, “I have expressed my heart to be shot at”.

Last year was the sixtieth anniversary of the publication of the Return of the King – the third and final volume of Lord of The Rings.

Pullman and others might note that the trilogy has sold a phenomenal 150 million copies worldwide; in 1997 it was Voted Amazon’s Best Book of the Century emerged as the most popular work of fiction in surveys by Waterstones and Channel Four and was second only to the Bible in its readership.

The Lord of the Rings sits alongside his wonderful short stories and The Silmarillion, posthumously brought to publication by his son, Christopher.

Pullman’s assessment was wrong about the book’s deep and abiding appeal and it is far from “trivial” – quite the reverse – and he was also wrong in stating that Tolkien’s was an unquestioning faith and that he had no doubts.

Referring to his doubts during a particularly arid period in the 1920s he said it was the Blessed Sacrament that kept his then flickering faith alive. He told his son, Michael “I brought you all up ill and talked to you too little. Out of wickedness and sloth I almost ceased to practice my religion…Not for me the Hound of Heaven but the never ceasing silent appeal to the Tabernacle and the sense of starving hunger.”

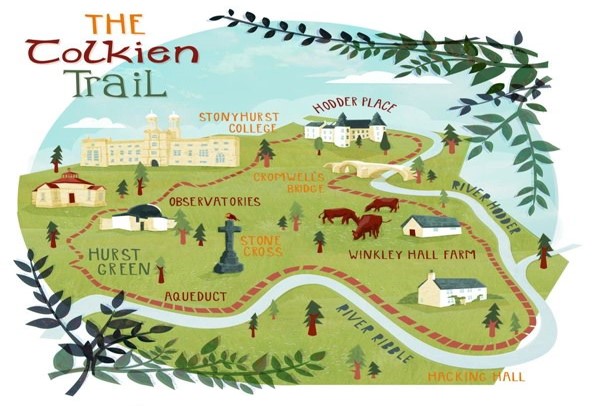

To consolidate his faith, he practiced and recommended frequent Confession and the frequent reception of Holy Communion, telling his son, Michael, who taught Classics at Stonyhurst College and St Mary’s Hall in Lancashire, “I put before you the one great thing to love on earth: the Blessed Sacrament. There you will find romance, glory, honour, fidelity and the true way of all your loves upon earth.”

In Oxford, he served Mass every day at Blackfriars. The Mass was celebrated by his fellow Inkling, Fr.Gervase Matthew OP. It is said that Whitacres’s Roman soldier, nailing Jesus to the Cross in the Stations of the Cross at Blackfriars is modelled on Tolkien’s orc.

Tolkien taught his children to love the Created world, especially the trees, and he persuaded Michael, to plant a copse in his Stonyhurst garden, evidence of which can still be seen today.

From 1939, after Mussolini joined forces with Hitler, Tolkien became a regular visitor to Stonyhurst when his oldest son, John, returned to England from seminary in Rome to continue his training as a priest. Stonyhurst – with its connections to the Shireburn family, to the recusants and Catholic martyrs, complete with its own Shire Lane in its village, with its two rivers and ancient forest and views of Pendle Hill, with its occult history, was an inspiring setting for Tolkien – captured beautifully today in the Ribble Valley Tolkien Trail.

Tolkien passed on his love of the Catholic faith to each of his children and encouraged his son, Christopher, to memorise some of the most tried and trusted prayers but also the entire text of the Latin Mass, saying that “If you have these by heart you never need for words of joy”; and he prayed the rosary, keeping a rosary by his bed and in his hands as he looked for Nazi bombers while part of the Oxford Watch during World War Two.

Towards the end of his life – even while the Jerusalem Bible was in the final stages of composition –Tolkien recoiled at liturgical changes and at what he regarded as a loss of beauty in both reverence for the Holy Eucharist and the sacraments and for the liturgy itself.

He was saddened but became reconciled to the use of the vernacular rather than Latin for the celebration of Mass but he deplored the use of sloppy language. He said that the encouragement of the faithful to receive Communion regularly and to attend daily Mass would have had a more profound effect on the Church than the reforms of the Second Vatican Council.

The changes led him to say “the Church which once felt like a refuge now often feels like a trap. There is nowhere else to go! I think there is nothing to do but pray for the Church, the Vicar of Christ, and for ourselves; and meanwhile to exercise the virtue of loyalty, which indeed only becomes a virtue when one is under pressure to desert it.” His grandson, Simon, wrote that he could “vividly remember going to church with him in Bournemouth.” He said that his grandfather didn’t agree with the liturgical changes “and made all the responses very loudly in Latin while the rest of the congregation answered in English. I found the whole experience quite excruciating, but my grandfather was oblivious. He simply had to do what he believed to be right.”

His belief in the sacrament of marriage and the love of family remained with him until the very end. When Tolkien died, on September 2nd, 1973 aged 81, he underscored that inseparability and indissolubility, by being interred in the same grave as his wife, Edith, who had died two years earlier. The names of Luthien and Beren appear on their tombstone.

In Tolkien’s Middle Earth Legendarium Luthien was the most beautiful of all the children of Iluvatar and forsook her immortality for her love of the mortal warrior Beren. The Silmarillion

The Hobbit

G.K.Chesterton

Fr.Robert Murray SJ

H.G.Wells

So much then for the experiences that shaped Tolkien.

- What does Tolkien Tells Us Himself about his faith?

While once on his knees before the Blessed Sacrament he personally experienced in a vision the blinding presence of God: “I perceived or thought of the Light of God” and saw his own Guardian Angel as a manifestation of “God’s very attention”.

As a Catholic he believed God is the Creator of the universe and that God had made the world out of nothing. Whether in the Bible or in Tolkien’s Silmarillion all that is has been created by the Word of God when, as we learn in the Book of Job, “the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God made a joyful melody.”

But as we also learn from The Silmarillion – as in the biblical story of Creation – we see the creativity of Iluvatar, the One, and his first creations, the Ainur, the Holy Ones, contested by Melkor, “the greatest of the Ainur” who, like Lucifer, falls as he succumbs to the sin of pride and seeks to subvert both men and elves.

As G.K.Chesterton said of such pride, and as Tolkien himself believed: “Pride does not go before a fall, pride is the fall.”

That Tolkien’s faith was based on personal encounter with God and a deep spirituality is revealed in an exchange that he had with a stranger (whom he identified with Gandalf) and who said to him “Of course, you don’t suppose, do you, that you wrote all that book yourself?” Tolkien replied “Pure Gandalf!…I think I said “No, I don’t suppose so any longer.” I have never since been able to suppose so. An alarming conclusion for an old philologist to draw concerning his private amusement. But not one that should puff up anyone who considers the imperfections of “chosen instruments”, and indeed what sometimes seems their lamentable unfitness for the purpose.”

All the elements, from the genesis and “the great music” of “The Silmarillion” to the awesome climax at Mount Doom, take us from the alpha of creation to the omega of judgement. This is a story that exists for itself.

Tolkien tells us that:

“The Lord of The Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work, unconsciously at first, but consciously in the revision”. Elsewhere he states “I am a Christian (which can be deduced from my stories), and in fact a Roman Catholic”. In 1958 he wrote that The Lord of the Rings is “a tale, which is built on or out of certain ‘religious’ ideas, but is not an allegory of them.”

In 1956 in a letter to Amy Ronald he wrote:

“I am a Christian, and indeed a Roman Catholic, so that I do not expect “history” to be anything but a long defeat – though it contains (and in a legend may contain more clearly and movingly) some samples or glimpses of final victory.”

Tolkien also said that his writing reflected his beliefs about death, immortality and resurrection.

In 1958, in a letter to Rhona Beare, Tolkien wrote:

“I might say that if the tale is ‘about’ anything it is not as seems widely supposed about ‘power.’ …It is mainly concerned with Death and Immortality.”

The Ring Rhyme that opens each volume of The Lord of the Rings reminds us of the order of Creation and that we cannot cheat our maker:

“Three rings for the Elven-kings under the sky,

Seven for the Dwarf-lords in their halls of stone,

Nine for Mortal Men doomed to die…”

The Silmarillion reminds us:

“Death is their fate, the gift of Iluvatar, which as Time wears even the Powers shall envy. But Melkor has cast his shadow upon it, and confounded it with darkness, and brought evil out of good and fear out of hope.”

Tolkien believed in the Catholic concept of Natural Law and in the natural order of things; that we must be good stewards of creation and guardians of the beauty that God has bestowed upon the created world.

He foresaw the battles over euthanasia, genetics and the immortality sought and craved through genetics and human cloning – the powerful temptation (shared by some of the men and elves of Tolkien’s realm) to artificially manipulate our allotted span of life and to upend Natural Law and to usurp the role of the Creator.

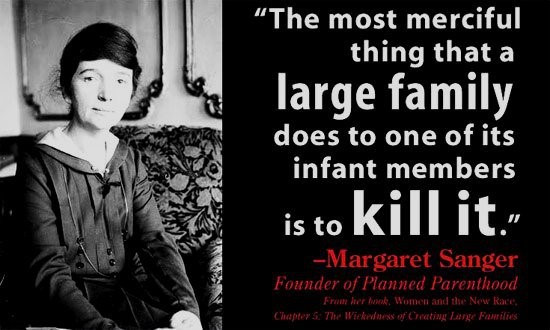

Tolkien and C.S.Lewis had read and were inspired by the writings of the Catholic convert G.K.Chesterton, who died in 1936, the year in which The Hobbit was completed. In 1922 Chesterton’s last book before becoming a Catholic was “Eugenics and Other Evils” in which he stood against Margaret Sanger and the other early cheer leaders for the Nazis and who literally argued for “More Children for the Fit. Less for the Unfit.” Sanger made it clear whom she considered unfit: “Hebrews, Slavs, Catholics, and Negroes.”

Chesterton argued that if people dared to challenge science without ethics, such as eugenics or cloning, attempts are made to belittle them with “the same stuffy science, the same bullying bureaucracy, and the same terrorism by tenth-rate professors.”

Tolkien shared Chesterton’s loathing of eugenics and in 1938 condemned Nazi “race-doctrine” as “wholly pernicious and unscientific”. And, after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he described the scientists who had created the atomic bomb as “these lunatic physicists” and “Babel-builders.”

Three years after Eugenics and Other Evils, Chesterton published his “The Everlasting Man” (1925) which disputed H.G.Wells’ view that civilisation was merely an extension of animal life and that Christ was no more than a charismatic figure. In contesting this, Chesterton said Christianity had “died many times and risen again; for it had a God who knew the way out of the grave.” Neither he nor Tolkien had any doubt about the Divinity of Christ, the Son of God.

In The Everlasting Man Chesterton paints the canvas of humanity’s spiritual journey and portrays Christianity as the bedrock of western civilisation.

Later, C.S.Lewis said that the combination of Chesterton’s apologetics and George MacDonald’s stories had between them shaped his intellect and imagination.

In 1947 Lewis wrote to Rhonda Bodle that “the [very] best popular defence of the full Christian position I know is G. K. Chesterton’s The Everlasting Man.” Having abandoned his atheism Lewis wryly remarked that a young man who is serious about his atheism cannot be too careful about what he reads.

Tolkien and Lewis were also influenced by Chesterton’s belief in Merrie England as an antidote to the pernicious dehumanisation represented by over industrialisation and the servile State.

The culture of the Shire is the culture of Merrie England.

Victorian Anglo-Catholics and Roman Catholics saw Merrie England as representing the abundance and generosity of gifts we so easily squander or spoil. There was something here of Thomas More’s Utopia and a desire to return to an idyllic pastoral way of life that had been superseded by the smoking chimneys and crushed character of 1930s Britain.

Chesterton saw Merrie England in the guise of the country inn, the Sunday roast, conversation around the fireside, through the medieval Guilds, arts and crafts. Tolkien captured these ideas in the people of the Shire.

He always made clear his intense hatred of the rapacious destruction of the English countryside and the desirability of the simple life. For most of his life Tolkien used a bicycle rather than a car, of which he though there were too many although it is unclear whether, like his Hobbits, he looked forward to two breakfasts

Tolkien and Lewis took from Chesterton their profound belief in the human dignity of every person, each made in the likeness and image of God. The castrating unmanning of men (“men without chests”) was captured by Lewis in “The Abolition of Man” (1943) and grotesque scientific brutalism is the theme of his novel “That Hideous Strength” (1945).

In 1930 Chesterton had observed that “When people begin to ignore human dignity, it will not be long before they begin to ignore human rights.”

And in his Autobiography (1936) he wrote this:

“I did not really understand what I meant by Liberty, until I heard it called by the new name of Human Dignity. It was a new name to me; though it was part of a creed nearly two thousand years old. In short, I had blindly desired that a man should be in possession of something, if it were only his own body. In so far as materialistic concentration proceeds, a man will be in possession of nothing; not even his own body. Already there hover on the horizon sweeping scourges of sterilisation or social hygiene, applied to everybody and imposed by nobody. At least I will not argue here with what are quaintly called the scientific authorities on the other side. I have found one authority on my side.”

Like Chesterton, Tolkien also insisted on the teaching authority of the Church and the Pope.

He said of the papacy: “I myself am convinced by the Petrine claims…for me the Church of which the Pope is the acknowledged head on earth has as chief claim that it is the one that has (and still does) ever defended the Blessed Sacrament, and given it most honour, and put it (as Christ plainly intended) in the prime place. “Feed my sheep” was his last charge to St.Peter.”

Chesterton and Tolkien also had a shared love of the Virgin Mary. In his poem “The Black Virgin” Chesterton describes Mary “a morning star” – “sunlight and moonlight are thy luminous shadows, starlight and twilight thy refractions are, lights and half-lights and all lights turn about thee.”

Tolkien gives his elves an invocation to Elbereth “We still remember, we who dwell in this far land beneath the trees, The Starlight on the Western seas” words redolent of a Marian hymn which describes Mary as the “guide of the wanderer”, as “the ocean star”, “mother of Christ, star of the sea”.

In a letter to Fr. Robert Murray SJ, Tolkien said of the Virgin Mary “Our Lady, upon which all my own small perceptions of beauty, both in majesty and simplicity is founded”. Elsewhere he had said: “I attribute whatever there is of beauty and goodness in my work to the Holy Mother of God.”

Tolkien saw Mary as the closest of all beings to Christ, as literally “full of grace” describing her as “unstained” and that “she had committed no evil deeds.” He saw her as the Christ bearer who paves the way for the Incarnation: about which he says “the Incarnation of God is an infinitely greater thing than anything I would dare to write.”

As well as is love of Mary, Tolkien had a traditional Catholic belief in the Communion of Saints – the companions of Christ throughout all the ages. He would have been delighted by the beatification in Birmingham, in 2010, by Pope Benedict of John Henry Newman. The collegiality – the fellowship – of Newman’s Oratorians appealed to Tolkien.

Newman insisted – and Tolkien believed – that there is some unique task assigned to each of us that has not been assigned to any other. The challenge is to discern it.

Newman’s prayer on “Purpose” emphasises each person’s unique gifts, their unique talents, and their unique destiny. he emphasised that we do not need to be perfect before using those talents. He said this about the use of gifts:

“What are great gifts but the correlative of great work? We are not born for ourselves, but for our kind, for our neighbours, for our country: it is but selfishness, indolence, a perverse fastidiousness, an unmanliness, and no virtue or praise, to bury our talent in a napkin.”

Or, for that matter, hide them in a private hobbit hole.

Tolkien loved the feasts and seasons of the Church and the ever growing company of saints. In 1925, when Tolkien was 33, the little flower” – the Carmelite nun, Saint Therese of Lisieux, was canonised. Her “little way” contradicted the elevation of power and the mobilisation of vast armies: “I only love simplicity. I have a horror of pretence” she said. “It is impossible for me to grow bigger, so I put up with myself as I am, with all my countless faults. But I will look for some means of going to heaven by a little way which is very short and very straight, a little way that is quite new.”

It sounds like a manifesto for Hobbiton.

Central, too, to Tolkien’s faith was his love of the Blessed Sacrament. He told his son Michael that “The only cure for sagging or fainting faith is Communion….frequency is of the highest effect.” He described the Holy Eucharist as “the one great thing to love on earth” and that in “the Blessed Sacrament you will find romance, glory, honour, fidelity and the true way of all your loves on earth, and more than that….eternal endurance which every man’s heart desires.”

And in all these battles Tolkien seeks the Viaticum which is given through the last of the seven Sacraments and which is provided as daily sustenance through the Sacrament of the Holy Eucharist stating:

“I fell in love with the Blessed Sacrament from the beginning and by the mercy of God never have fallen out again”

These then are some of the “certain ‘religious’ ideas” that inspired Tolkien.

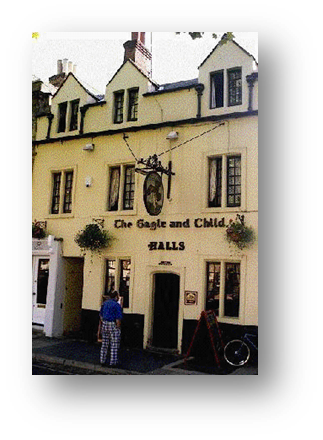

Doubtless, all of these beliefs and ideas were the subject of discussion when the Inklings met at the Eagle and Child – the Bird and Baby – between the 1930s and 1949. The group was led by Tolkien and Lewis but also included Tolkien’s son, Christopher, Roger Lancelyn Green, Hugo Dyson, Owen Barfield, Charles Williams and Lord David Cecil.

But it was particularly the companionship of C.S.Lewis that strengthened the faith of both men.

It is now 90 years since J.R.R.Tolkien and C.S.Lewis met as Oxford academics.

It was the beginning of a friendship kindled by common experiences and which produced some of the most wonderful fiction of the twentieth century but which had its origins in the shared horrors of the Great War.

Lewis once wrote that “There’s no sound I like better than male laughter” – and it was in the early 1930s that he began to cultivate his friendship with the new Professor of Anglo-Saxon, appointed in 1925. Throughout those highly productive years – and as he journeyed from atheism to Christian belief – Lewis became close to Tolkien.

In 1933 they began to hold meetings in college rooms and on Tuesday mornings at The Eagle and Child. Tolkien later wrote that “CSL had a passion for hearing things read aloud.” The Inklings met regularly during the next two decades.

Although Tolkien would later be displaced in Lewis’ affections, and a rift opened between them, these gatherings inestimably enriched them both.

Lewis would write of the importance of such friendship in “The Four Loves”: “He is lucky beyond desert to be in such company. Especially when the whole group is together, each bringing out all that is best, wisest or funniest in all the others.”

The Inklings were conceived as a circle of friends which would practice solidarity and engender camaraderie; intuitively and challengingly counter cultural.

For Lewis the Inklings also provided a familial intimacy which his own family could not. Tolkien was crucial in his own journey to faith.

He recorded the moment when, in 1931, he decided to embrace Christianity: “I have just passed on from believing in God to definitely believing in Christ – in Christianity. …My long night talk with Dyson and Tolkien had a good deal to do with it.”

Two year earlier he had come to believe in God:

“In the Trinity Term of 1929 I gave in, and admitted that God was God, and knelt and prayed: perhaps, that night, the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England…The hardness of God is kinder than the softness of men, and His compulsion is our liberation.”

Lewis and Tolkien did not believe Christians needed to be morose or detached. In 1944 The Daily Telegraph misleadingly referred to Lewis as “an ascetic”. Tolkien scoffed at this in a letter to his son: “Ascetic Mr. Lewis!!! I ask you! He put away three pints in a very short session we had this morning and said he was ‘going short for Lent.’”

Their friendship was based on the joy to which Lewis gave so much emphasis in his writing and captured by Tolkien in this verse from Lord of the Rings:

“Ho! Ho! Ho!

To the bottle I go To heal my heart and drown my woe Rain may fall, and wind may blow And many miles be still to go But under a tall tree will I lie And let the clouds go sailing by”

For two men formed in the harrowing trenches of the Great War, who had seen so many of their friends pay the ultimate price, pain and suffering did not disable or incapacitate them. Both believed that beyond the pain and the suffering of today is the certainty of eternity. Both believed that through their story telling they could encourage their readers to see beyond the catastrophic and destructive effects of war and the evil in our world to a hopeful and joyous future.

So much, then, for Tolkien’s beliefs and the experiences which shaped him.

- 2. How does that faith shape the characters, and the story lines?

Although Tolkien despised simple allegory he invites us to use the stories, the plots, the characters, and to examine their “applicability.” He said that his objective had been to “make a body of more or less connected legend…drawing splendour from vast backcloths…The cycles should be linked to a majestic whole and yet leave scope for other minds and hands, wielding paint and music and drama.” He said that his work should be “dedicated simply to England, to my country.”

This suggests that he wants us to explore his amazing and extraordinary landscape to discover things that are important about how we live and behave towards one another.

Tolkien insisted that notwithstanding the Redemption of man “the Christian still has to work, with mind as well as body” and he said that “in Fantasy he may actually assist in the effoliation and multiple enrichment of creation.”

We are being invited to decipher his elvish runes and games of riddles, leaving us scope to draw what conclusions we may but this is an invitation to meet our Creator through legend and myth, fantasy and story-telling.

And the Lord of the Rings is riddled with wisdom and common sense about everything from the nature of friendship to the place of courage:

“If more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded gold, it would be a merrier world.”

“I don’t know half of you half as well as I should like; and I like less than half of you half as well as you deserve.”

It’s the job that’s never started as takes longest to finish.”

“Little by little, one travels far.”

“Still round the corner there may wait, a new road or a secret gate”

“Faithless is he that says farewell when the road darkens.”

“It’s a dangerous business going out your front door.”

“Courage is found in unlikely places.”

But central must be an understanding of power and evil represented by the Ring itself:

“The Board is set, the pieces are moving. we come to it at last, the great battle of our time.”

Stratford Caldecott believed that the Ring exemplifies “the dark magic of the corrupted will, the assertion of self in disobedience to God. It appears to give freedom, but its true function is to enslave the wearer to the Fallen Angel. It corrodes the human will of the wearer, rendering him increasingly “thin” and unreal; indeed, its gift of invisibility symbolizes this ability to destroy all natural human relationships and identity. You could say the Ring is sin itself: tempting and seemingly harmless to begin with, increasingly hard to give up and corrupting in the long run“

The Ring and the forces at work capture the endless contest between good and evil. It represents naked power and crude evil bringing with it temptation and corruption, violence and death.

As the ring bearer struggles towards his destiny many die before the evil forces of Sauron are at last subdued; and even then Saruman remains at large in the Shire – evil and sin are still at work, waiting to ensnare us.

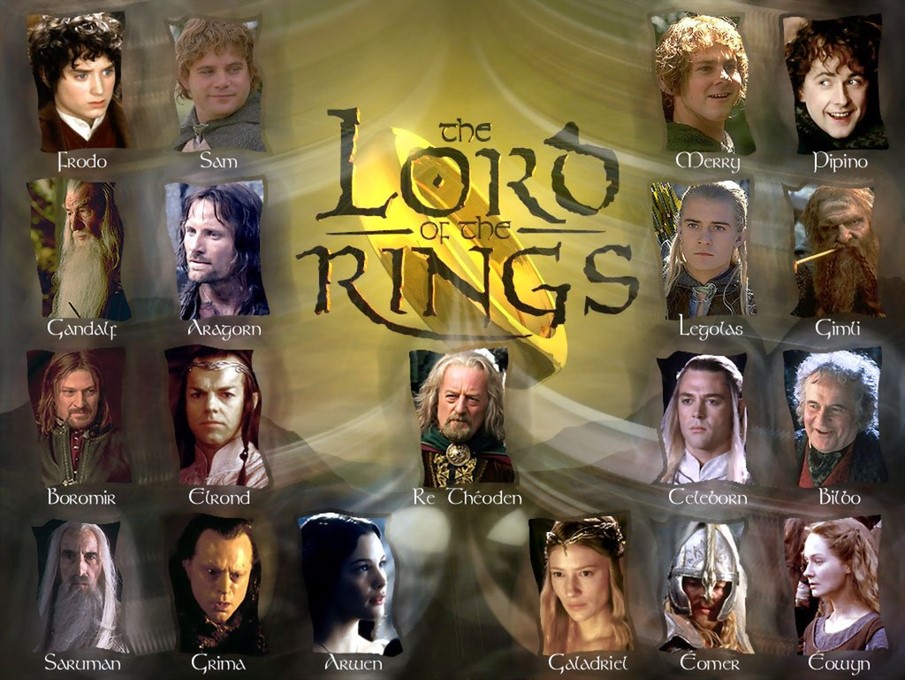

For the Christian, the use of evil to overcome evil is a frequent temptation. Frodo, Gandalf and the Lady Galadriel all understand that if they use the ring to overcome the Dark Lord then they too will become enslaved by evil.

The general weakness of humanity (which can be taken to cover not only mankind, but all creatures in The Lord of the Rings) reminds us that humanity is fundamentally good, but that those who fall turn to evil.

All that is evil was once good – Elrond says, “Nothing was evil in the beginning. Even Sauron was not so.” In this commentary and in the fallen orcs – which were themselves once elves – we can surely see the story of the fall.

Temptation appears first in The Hobbit as the travellers are warned as they enter Mirkwood, don’t drink the water and don’t stray from the path. How like the descendants of Adam, who when urged not to eat at the forbidden tree choose do so anyway.

The temptation of the Serpent is reflected in Boromir’s temptation by the Ring, as well as in Gollum’s. In Gollum we also see the idea of a conscience – he fights with himself and with his conscience while he is being tempted. The theologian Colin Gunton was of the opinion that the way in which the Ring tempts people to use its power is analogous to Jesus’ temptation by the devil.

Other aspects of evil also recur in the book. The destructive nature of evil is there in the Scouring of the Shire, and in the way in which Saruman’s troops destroy the trees and the timeless quality of Shire life, something especially abhorrent to Tolkien. The orcs themselves are cannibals, and are hideous – showing how evil corrupts. The dark and barren lands of Mordor are the very face of evil.

Connected with this is the self-destructive nature of evil. Inherent in evil is the desire to dominate, rule and have power over others.

After Gollum falls to the power of the Ring, he is consumed by its power, and he becomes weakened to such an extent that he can no longer resist it. Even getting close to evil has a subverting effect: take Bilbo’s reluctance to give up the Ring, and its disappearance from the mantle piece and reappearance in his pocket. Or, despite his epic and heroic journey into darkness, Frodo ultimately fails to throw the ring into the furnace. Here is the powerful mixture of the intoxicating allure of the forbidden with our human weakness and frailty.

Yet, despite his failure, in Frodo’s “little way” of self-sacrifice and willingness to take on seemingly impossible odds we see a central tenet of Christian belief. And think of those unlikely victories over seemingly intractable and daunting odds such as at Helm’s Deep. Even when evil appears to be triumphing – such as when Sauron gloats over what he considers to be the foolhardiness of Aragorn’s troops as they march towards Mordor, he is defeated by them.

Evil also brings with it desolation, barrenness and the destruction of beauty.

Compare the destruction of Isengard, and the brutality of the orcs, with the simple homely life of the Shire. An image that Tolkien repeatedly uses is that of dark and light. Contrast the Shire and Mordor (“where the shadows lie”) – The Shire which contains so much of the England Tolkien loved, and Mordor, the dark and sinister land where Sauron and Mount Doom are to be found, and which contains so much of the England that Tolkien hated.

Compare, too, the man-eating trolls and orcs with the elves – the disfigured (fallen) creatures and the beautiful and immortal elves – comparable to the angelic hosts. Recall the crucial role of the eagles and remember Isaiah 40:31 that “Those who hope in the Lord will renew their strength. They will soar on wings like eagles; they will run and not grow weary, they will walk and not be faint.”

Even in his use of names Tolkien’s sign posts take us to places and people that seem good or bad – Galadriel, Aragorn, Frodo and Arwen are beautiful-sounding names, whereas Wormtongue, the Balrog, Mordor and Mount Doom -all unlikely to be forces for good.

But although we encounter evil we are encouraged never to lose sight of what is good:

“The world is indeed full of peril, and in it there are many dark places; but still there is much that is fair, and though in all lands love is now mingled with grief, it grows perhaps the greater.”

In the Lady Galadriel the reader can be allowed to see something of the purity and beauty of the Virgin Mary; Galadriel’s grand-daughter, Arwen, also has a Marian role, saving both Frodo’s life and soul as she utters the words – not in the original text but crafted by Peter Jackson, who in his use of the word grace makes a more explicitly religious statement than even Tolkien himself –

“What grace is given me, let it pass to him. Let him be spared.”

Galadriel bestows upon the Fellowship seven mystical gifts, which are surely analogous to the seven sacraments, and as such are real signs of grace, and not mere symbols.

In the provision of lembas, we can see the Holy Eucharist. Before the Fellowship depart from Lorien they have a final supper where the mystical elvish bread lembas is shared, and they all drink from a common cup. The immortal elves are nourished by the lembas, the mystical bread – the bread of angels – which both nourishes and heals.

Lembas, we are told, “had a potency that increased as travellers relied on it alone, and did not mingle it with other goods. It fed the will, and it gave strength to endure.” This allusion reminds us of the manna that fed the people of Israel or the German mystic, Theresa Neumann, who survived by eating nothing other than the Holy Eucharist.

We can see Christ-like qualities in Aragorn. He has a kingdom to come into, a bride to wed. One powerful image is of the “Hands of the Healer” – in the Houses of Healing: Aragorn, the King, has the ability to heal people by touching them with his hands. Another King had the touch that healed Jairus’ daughter, the centurion’s servant, the lepers, the blind man and the sick who were lowered through the roof at Capaernum.

Aragorn, Gandalf, and Frodo all have Christ like marks – with Aragorn the king entering his kingdom, the return of whom everyone is expecting;

In Gandalf we are also confronted by Resurrection –a life beyond the present is evoked as Gandalf dies after he fights the Balrog on the Bridge of Khazad-Dum; but returns – and is initially unrecognised, strengthened as Gandalf the White; recalling Gethsemane and Emmaus.

Gandalf’s transformation tells us something about the Christian idea of justice, which is at the heart of the book. In the end, everyone gets what they deserve. Saruman starts off as Saruman the White, but following his fall, ends up as Saruman of Many Colours. The order of “rank” in the wizard hierarchy holds white as the highest, followed by grey and then brown; they almost sound like orders of monks and friars with Gandalf the Grey becoming Gandalf the White.

There is even a sort of papacy in the wizard Gandalf – after all, he acts as leader to the free and faithful people, and he even crowns kings, as did popes of old. And as a spiritual father to Frodo, who tells Gandalf that he wishes he had not been born into such a time as this that “All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to us.”

There is the further thought that along with Galdalf’s papal colour of white, the name of the Pope’s summer residence, Castel Gandolfo, is translated into English as Gandolf’s Castle. Perhaps it means nothing; perhaps it is another elvish rune.

In Boromir we see a willingness to lay down his life for his friends (made all the more remarkable because of his earlier attempt to seize the ring by force and by his subsequent repentance). Boromir is rewarded for his repentance by dying a hero’s death by an orc’s arrow and being given a hero’s funeral. All of the fallen characters are given a chance to repent, although most of them– such as Wormtongue, Gollum and Saruman – unlike Boromir, do not.

In Frodo, we see a willingness both to serve and to carry his burden. The very future of Middle Earth is at stake, and it is the Fellowship which wins salvation for Middle Earth, although not without cost, including self-sacrifice.

Elrond tells Frodo that it is his destiny to be a ring bearer; but this is no pleasurable occupation. Frodo, like Christ, takes up his cross.

Throughout the quest Frodo’s strength in increasingly sapped by the burden he carries and of which he seeks to be rid. His stumbling approach to Mordor, under the Eye of Sauron, is like the faltering steps of Christ weighed down by his Cross as he repeatedly falls on the path to Golgotha; and, like Christ, Frodo is tempted by despair.

Indeed, Frodo does succumb. His free will, hitherto so strong in resisting the powers of the Ring, gives way to the power of the Ring, and he cannot bring himself to throw it down into the fires of Mount Doom. Despite all his inner strength Frodo gradually succumbs to a dark fascination with the ring and he loses his free spirit and free will the closer he comes in proximity to Mount Doom

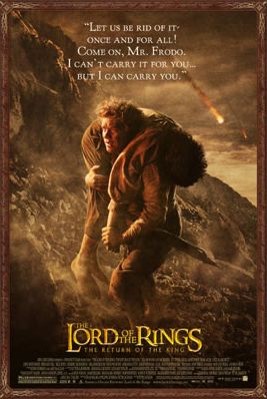

Enter here the Christian foot soldier, Samwise Gamgee.

My own favourite character in The Lord of the Rings is based on the private soldiers Tolkien encountered at the Somme in 1916:

“My Sam Gamgee is indeed a reflection of the English soldier, of the privates and batmen I knew in the 1914 War, and recognised as so far superior to myself.”

Sam’s humility turns him into the greatest hero in the book. Although he is only Frodo’s gardener, it is he who saves Frodo and ultimately the Shire. Mary Magdalene, in her first resurrection encounter with the Lord mistakes Jesus, thinking that he too is only a gardener. Tolkien is reminding us that so often we miss what is important about the people we meet, what matters most, and too frequently judge them by the job they do or their social origins.

Sam is like Simon of Cyrene, sharing his Master’s burden and at the climax his devoted loyalty in following Frodo to the very end is rewarded as the burden is lightened and he is transfigured.

Stratford Caldecott quotes Tolkien as saying that the plot is concerned with ‘the ennoblement (or sanctification) of the humble’ – and the meek Sam certainly inherits the earth.

At a crucial moment in Mordor he must carry the Ringbearer, and even the Ring itself. He moves from immature innocence to mature innocence: and finally, in his own world (that is, in Tolkien’s inner world of the Shire), this ‘gardener’ becomes a ‘king’ or at least a Mayor. The fact is that Frodo could not have fulfilled his task without the continuing presence of Sam, and he relies utterly on him; yet Sam remains humble always and faithful to his master.

Through Sam Tolkien also reminds us of the Christian virtue of mercy and the role of Providence. Sam would have gladly disposed of Gollum whom he sees as a threat to Frodo. Gandalf commends Frodo for showing mercy and tells us that even Gollum may one day have his moment. As the ring is committed to the depths that Providence comes to pass.

As Sam, who begins the story by eavesdropping, returns to the Shire there is something of the Catholic love of order, tradition and a longing for restoration of that which has been lost.

Sam insists “there is some good in this world. And it’s worth fighting for.”

The fight culminates on a specific date: March 25th. It is the day on which the Ring is finally destroyed at Mount Doom. Gandalf tells Frodo “the New Year will always now begin on the 25th of March when Sauron fell, and you were brought out of the fire to the King.”

Tom Shippey, in “The Road to Middle Earth”, says that in “Anglo-Saxon belief, and in European popular tradition both before and after that, March 25th is the date of the Crucifixion”, and it is also the date of the Annunciation. Days to recall beginnings and endings.

The Lord of the Rings then is a story with many stories concealed within it. Tolkien’s subtlety is that he lays a trail of clues for his readers.

His final hidden clue – the last elvish rune – is the word Tolkien invented to describe what he saw as a good quality in a fairy-story – and that word was eucatastrophe, this being the notion that there is a “sudden joyous ‘turn’” in the story, where everything is going well, “giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy”, whilst not denying the “existence of dyscatastrophe – of sorrow and failure”.

Tolkien said:

“I concluded by saying that the Resurrection was the greatest ‘eucatastrophe’ possible in the greatest Fairy Story – and produces that essential emotion: Christian joy which produces tears because it is qualitatively so like sorrow, because it comes from those places where Joy and Sorrow are at one, reconciled, as selfishness and altruism are lost in Love.“

That is what shaped his life, what shaped his beliefs, where faith and fiction are joined as one – and why his work is a great spiritual adventure as well as high fantasy at its very best.

David Alton, November 2016.