2015: Christians, Christmas, and The Growing Wave of Intolerance….

Last year, the Sultan of Brunei introduced Sharia criminal law, which allows for punishments including stoning, whipping and amputation. This year, following in the footsteps of Lenin and Stalin, he has banned Christmas celebrations.

And when Somalia, with its history of Al-Shabaab atrocities, lines up in imitation, it should give the Sultan cause to reflect. All the world over we should rejoice in one another’s religious festivals. They can enrich and inspire communities.

Remember that in Russia, the Communists replaced St. Nicholas with “Did Moroz,” or Grandfather Frost. Christmas trees were banned and Stalin folded all Christmas celebrations into secular New Year celebrations. Communists in Vietnam forbade children’s choirs to sing “Silent Night.” and Christmas was banned in Cuba.

In 1983, in Communist Romania, under the dictatorship of Ceaucescu, a Roman Catholic priest, Father Geza Palffy, preached against Ceaucescu’s diktat that December 25th would be a a work day, not a holiday. The following morning the Securității Statuluihe – the secret – arrested him. He was beaten, imprisoned and died.

Soviet Communists rewrote a much-loved Ukrainian Christmas carol, “Nova Radist Stala” (Joyous News Has Come to Us), replacing it with the words “The joyous news has come which never was before. Long-awaited star of freedom lit the skies in October [the month of the Revolution]. Where formerly lived the kings and had the roots their nobles, there today with simple folks, Lenin’s glory hovers.”

As he now joins such company, the Sultan should remember that these attempts to crush the Christmas message all failed. Yet, actions like his can provide a licence to those who wish to disrespect those minorities, of whatever faith, who live in their midst. Such actions jeopardise the fragile relationships of the many communities and countries where men and women strive to live alongside one another.

In more than one hundred countries – from Syria to North Korea, from Nigeria to Iraq – Christians face genocide, crimes against humanity, torture, imprisonment, persecution or discrimination.

As we celebrate this great Christmas feast we know that waiting in the wings, and remembered by Christians on the days which follow, are the martyrdom of Stephen and the murder of the holy innocents.

What a tragedy that the 21st century – replete with beheadings, rape, abductions, torture and vast numbers of refugees – still witnesses such cruelty and barbarism. The great challenge facing people of all faiths and none is how to learn to respect the dignity of difference and to live peaceably alongside one another in mutual respect.

Somalia and Tajikistan follow Brunei in banning the celebration of Christmas:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-35167726

| BOKO HARAM KILL 14 CHRISTIANS ON CHRISTMAS DAY 2015 | ||||||

|

G. K. Chesterton once said that the world would never starve for wonders, but only for the want of wonder.

Extracts from G.K. Chesterton on celebrating Christmas…

It is the very essence of a festival that it breaks upon one brilliantly and abruptly, that at one moment the great day is not and the next moment the great day is. Up to a certain specific instant you are feeling ordinary and sad; for it is only Wednesday. At the next moment your heart leaps up and your soul and body dance together like lovers; for in one burst and blaze it has become Thursday. I am assuming (of course) that you are a worshipper of Thor, and that you celebrate his day once a week, possibly with human sacrifice. If, on the other hand, you are a modern Christian Englishman, you hail (of course) with the same explosion of gaiety the appearance of the English Sunday. But I say that whatever the day is that is to you festive or symbolic, it is essential that there should be a quite clear black line between it and the time going before. And all the old wholesome customs in connection with Christmas were to the effect that one should not touch or see or know or speak of something before the actual coming of Christmas Day

Of course, all this secrecy about Christmas is merely sentimental and ceremonial; if you do not like what is sentimental and ceremonial, do not celebrate Christmas at all. You will not be punished if you don’t; also, since we are no longer ruled by those sturdy Puritans who won for us civil and religious liberty, you will not even be punished if you do. But I cannot understand why any one should bother about a ceremonial except ceremonially. If a thing only exists in order to be graceful, do it gracefully or do not do it. If a thing only exists as something professing to be solemn, do it solemnly or do not do it. There is no sense in doing it slouchingly; nor is there even any liberty. I can understand the man who takes off his hat to a lady because it is the customary symbol. I can understand him, I say; in fact, I know him quite intimately. I can also understand the man who refuses to take off his hat to a lady, like the old Quakers, because he thinks that a symbol is superstition. But what point would there be in so performing an arbitrary form of respect that it was not a form of respect? We respect the gentleman who takes off his hat to the lady; we respect the fanatic who will not take off his hat to the lady. But what should we think of the man who kept his hands in his pockets and asked the lady to take his hat off for him because he felt tired?

This is combining insolence and superstition; and the modern world is full of the strange combination. There is no mark of the immense weak-mindedness of modernity that is more striking than this general disposition to keep up old forms, but to keep them up informally and feebly. Why take something which was only meant to be respectful and preserve it disrespectfully? Why take something which you could easily abolish as a superstition and carefully perpetuate it as a bore? There have been many instances of this half-witted compromise. Was it not true, for instance, that the other day some mad American was trying to buy Glastonbury Abbey and transfer it stone by stone to America? Such things are not only illogical, but idiotic. There is no particular reason why a pushing American financier should pay respect to Glastonbury Abbey at all. But if he is to pay respect to Glastonbury Abbey, he must pay respect to Glastonbury. If it is a matter of sentiment, why should he spoil the scene? If it is not a matter of sentiment, why should he ever have visited the scene? To call this kind of thing Vandalism is a very inadequate and unfair description. The Vandals were very sensible people. They did not believe in a religion, and so they insulted it; they did not see any use for certain buildings, and so they knocked them down. But they were not such fools as to encumber their march with the fragments of the edifice they had themselves spoilt. They were at least superior to the modern American mode of reasoning. They did not desecrate the stones because they held them sacred.

Let us be consistent, therefore, about Christmas, and either keep customs or not keep them. If you do not like sentiment and symbolism, you do not like Christmas; go away and celebrate something else; I should suggest the birthday of Mr. M’Cabe. No doubt you could have a sort of scientific Christmas with a hygienic pudding and highly instructive presents stuffed into a Jaeger stocking; go and have it then. If you like those things, doubtless you are a good sort of fellow, and your intentions are excellent. I have no doubt that you are really interested in humanity; but I cannot think that humanity will ever be much interested in you. Humanity is unhygienic from its very nature and beginning. It is so much an exception in Nature that the laws of Nature really mean nothing to it. Now Christmas is attacked also on the humanitarian ground. Ouida called it a feast of slaughter and gluttony. Mr. Shaw suggested that it was invented by poulterers. That should be considered before it becomes more considerable.

I do not know whether an animal killed at Christmas has had a better or a worse time than it would have had if there had been no Christmas or no Christmas dinners. But I do know that the fighting and suffering brotherhood to which I belong and owe everything, Mankind, would have a much worse time if there were no such thing as Christmas or Christmas dinners. Whether the turkey which Scrooge gave to Bob Cratchit had experienced a lovelier or more melancholy career than that of less attractive turkeys is a subject upon which I cannot even conjecture. But that Scrooge was better for giving the turkey and Cratchit happier for getting it I know as two facts, as I know that I have two feet. What life and death may be to a turkey is not my business; but the soul of Scrooge and the body of Cratchit are my business. Nothing shall induce me to darken human homes, to destroy human festivities, to insult human gifts and human benefactions for the sake of some hypothetical knowledge which Nature curtained from our eyes. We men and women are all in the same boat, upon a stormy sea. We owe to each other a terrible and tragic loyalty. If we catch sharks for food, let them be killed most mercifully; let any one who likes love the sharks, and pet the sharks, and tie ribbons round their necks and give them sugar and teach them to dance. But if once a man suggests that a shark is to be valued against a sailor, or that the poor shark might be permitted to bite off a man’s leg occasionally; then I would court-martial the man–he is a traitor to the ship.

Meanwhile, it remains true that I shall eat a great deal of turkey this Christmas; and it is not in the least true (as the vegetarians say) that I shall do it because I do not realise what I am doing, or because I do what I know is wrong, or that I do it with shame or doubt or a fundamental unrest of conscience. In one sense I know quite well what I am doing; in another sense I know quite well that I know not what I do. Scrooge and the Cratchits and I are, as I have said, all in one boat; the turkey and I are, to say the most of it, ships that pass in the night, and greet each other in passing. I wish him well; but it is really practically impossible to discover whether I treat him well. I can avoid, and I do avoid with horror, all special and artificial tormenting of him, sticking pins in him for fun or sticking knives in him for scientific investigation. But whether by feeding him slowly and killing him quickly for the needs of my brethren, I have improved in his own solemn eyes his own strange and separate destiny, whether I have made him in the sight of God a slave or a martyr, or one whom the gods love and who die young–that is far more removed from my possibilities of knowledge than the most abstruse intricacies of mysticism or theology. A turkey is more occult and awful than all the angels and archangels In so far as God has partly revealed to us an angelic world, he has partly told us what an angel means. But God has never told us what a turkey means. And if you go and stare at a live turkey for an hour or two, you will find by the end of it that the enigma has rather increased than diminished.

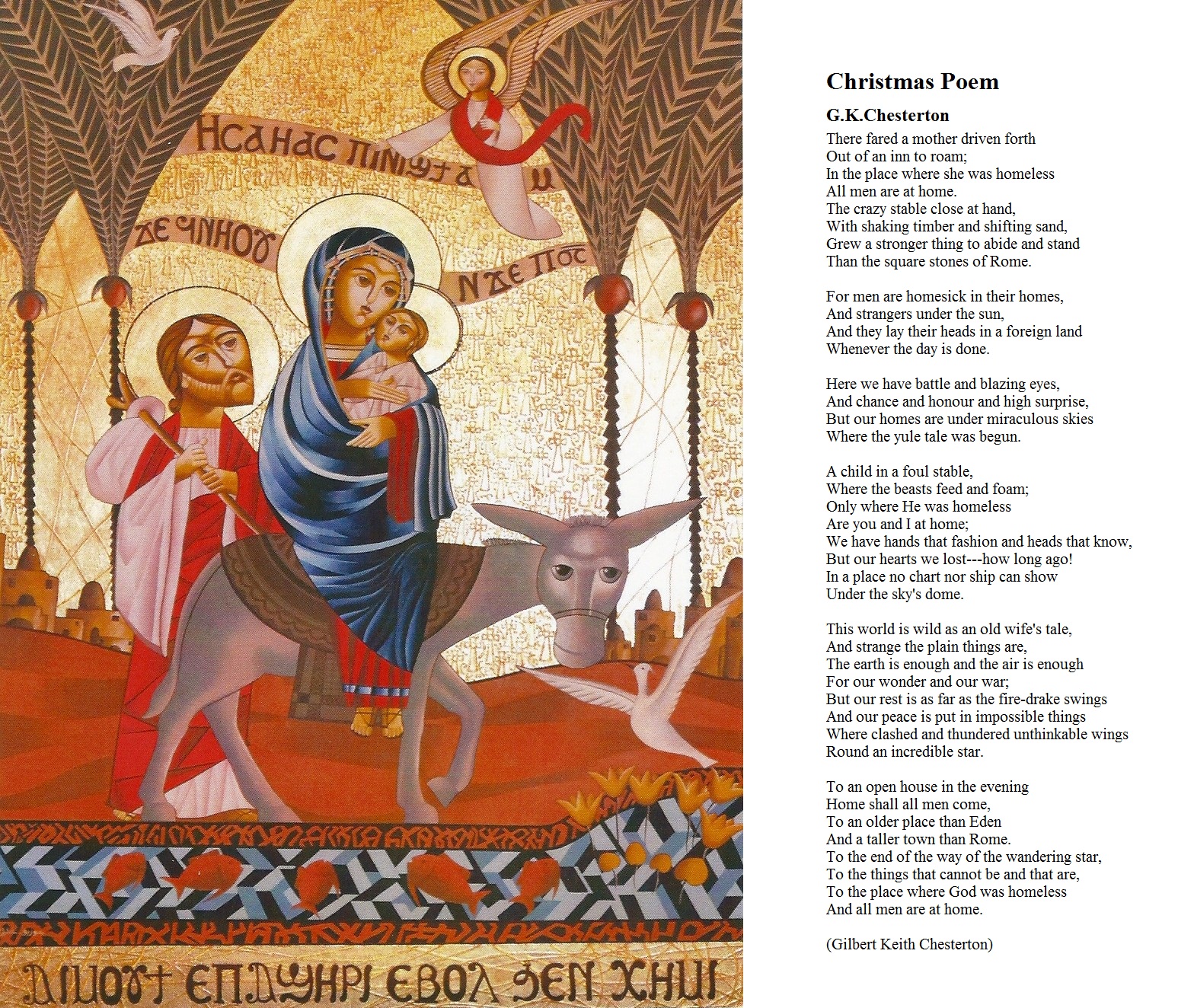

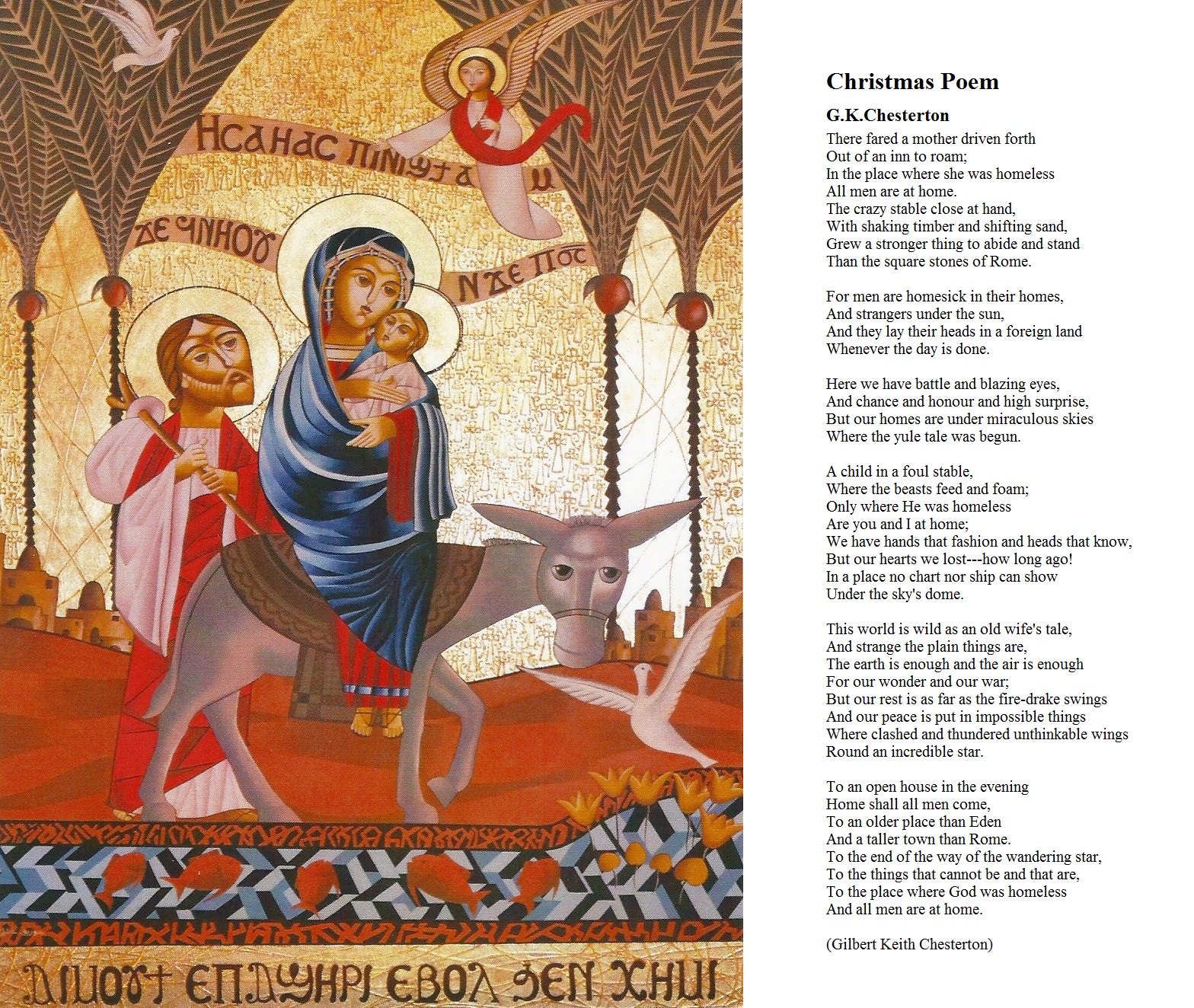

The House of ChristmasG.K. Chesterton

By: G. K. ChestertonThere fared a mother driven forth

Out of an inn to roam;

In the place where she was homeless

All men are at home.

The crazy stable close at hand,

With shaking timber and shifting sand,

Grew a stronger thing to abide and stand

Than the square stones of Rome.For men are homesick in their homes,

And strangers under the sun,

And they lay on their heads in a foreign land

Whenever the day is done.

Here we have battle and blazing eyes,

And chance and honour and high surprise,

But our homes are under miraculous skies

Where the yule tale was begun.A Child in a foul stable,

Where the beasts feed and foam;

Only where He was homeless

Are you and I at home;

We have hands that fashion and heads that know,

But our hearts we lost – how long ago!

In a place no chart nor ship can show

Under the sky’s dome.This world is wild as an old wives’ tale,

And strange the plain things are,

The earth is enough and the air is enough

For our wonder and our war;

But our rest is as far as the fire-drake swings

And our peace is put in impossible things

Where clashed and thundered unthinkable wings

Round an incredible star.To an open house in the evening

Home shall men come,

To an older place than Eden

And a taller town than Rome.

To the end of the way of the wandering star,

To the things that cannot be and that are,

To the place where God was homeless

And all men are at home.—————————————————————————————————-The worth of a disabled person’s life:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jx_U_BlMYu4…and two seasonal links to cheer you up http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vZrf0PbAGSkhttp://www.stcatharinesstandard.ca/ArticleDisplay.aspx?e=2852416

In a children’s picture story book which we have at home there is an illustration of Santa Claus reading a story to the baby Jesus. The narrative is the baby’s own story – the story of the child’s birth in a stable, comforted by his mother, protected by Joseph, surrounded by shepherds and angels, warmed by the donkey and the ox, and with the Magi and their gifts to follow. The perfect scene is almost magical, but, asks the baby “how does it all end?”. How does it all end?

Without losing anything of the innocence and purity of that moment, and because we know only too well the answer to the infant’s question, the story reminds us to be realistic about Christmas.

We know what is inevitably coming, what is waiting in the wings. We will share with the Catholic writer, J.R.R.Tolkien, the belief that history “is a long defeat” but with “glimpses of the final victory.”

It is precisely because the story won’t end at Golgotha but in Jerusalem’s empty tomb that sense can be made of the breaking of the Christmas spell and of the defeats, the suffering, the rejection and pain which will face the child and His family from the moment He leaves the shelter of Bethlehem’s stable – going into exile, as the people of Israel did before Him.

As all these events unfold I am always struck by the proximity of that greatly derided animal, the donkey . Always a star attraction in every school’s nativity play my eldest son, Padraig, made his acting debut as the Christmas donkey.

Although the donkey appears nowhere in the Gospel the donkey is firmly fixed in our imaginations. The prophet Isaiah certainly foretold a central role for this most maligned of creatures: “The ox knows his owner, and the donkey his master’s crib.”

The donkey carries the unborn Jesus in Mary’s womb as they travel to Bethlehem for the census. The donkey is at close quarters during the child’s birth. The donkey enables Joseph to make good their escape as they are pursued by Herod’s killers and make their escape to Jerusalem. And, all those years later, it is the donkey, ho bears the King through the palm waving crowds as He enters Jerusalem.

G.K.Chesterton immortalised the value of the donkey in some verse which takes the animal’s name:

” When fishes flew and forests walkedAnd figs grew upon thornSome moment when the moon was bloodThen surely I was born. With monstrous head and sickening cryAnd ears like errant wings,The devil’s walking parody On all four-footed things. The tattered outlaw of the earth Of ancient crooked will:Starve, scourge, deride me–I am dumb–I keep my secret still. Fools! for I also had my hour,One far, fierce hour and sweetThere was a shout about my earsAnd palms before my feet.”

What Chesterton is reminding us is that God sees us differently from the way in which we see ourselves and from the way we see one another.

The donkey is chosen above the stallion to bear the King of Kings; the tattered, unloved, and unattractive creature which is used for menial hard labour, despised and marked out for servitude, and endures the worst of things, is chosen above all others for this wondrous moment – and we cannot take that away from him.

The donkey’s humble but sturdy and dependable frame contradicts a world which places too much value on the right social connections; on outward appearance and displays of ephemeral and passing beauty; on what we have rather than what we give; and on what we own rather than who we are. Ultimately, the donkey understands this typical Chestertonian paradox and internalises the knowledge that regardless of how the world sees him, he has true value and intrinsic worth.

In making us look at the donkey isn’t Chesterton making us look at ourselves? And making us consider how God sees us?

Beyond the banter which many of us might recall from school days – of being chided by schoolmasters as donkeys for some act of stubbornness or stupidity – is a harsher imagery: the large swathes of humanity that feel crushed or borne down by their burdens, unable to escape from the servitude of exploitative labour or trapped in unfulfilling or unappreciated employment or relationships. Through those eyes we can surely understand how the donkey must feel.

As this year comes to its conclusion I think back to some of the people I have met in recent times and to places where people are treated no differently from beasts of burden.

I think of some of India’s Dalit people in West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh and Delhi, who are marked out by caste as untouchable people.

The word Dalit comes from a Sanskrit word meaning “broken” or “crushed” – and like those other beasts of burden – the Dalit people, a quarter of India’s population, are used for menial tasks such as scavenging and the cleaning of latrines.

In my study I have a small terracotta pot given to me by Dr Joseph D’Souza, President of the International Dalit Freedom Network.

Once a Dalit has drunk from the pot they must break it – so as not to pollute or contaminate other castes who might come into contact with it. It is not the pots which need to be broken, not the people, but this monstrous system which ensnares them.

I have also been thinking about the people I met in Africa in October.

Although South Sudan has become an independent nation, the killing in South Kordofan and Blue Nile continues at the behest of Khartoum’s northern regime, already indicted for crimes against humanity in Darfur. These, too, are a people who have been crushed and burdened – two million died during the civil war a decade ago; and during the past twelve months more people died in Southern Sudan than even in Darfur.

In the summer I once again met the brave Bishop Macram Gassis, who has spent many years defying assassination attempts, and who courageously continues to work for peace and justice:

Surely, this Christmas, we will be praying for an enduring peace, for justice, and for the upholding of human dignity in Sudan.

And I will also be thinking of Burma – and the release of Aung San Suu Kyi – and of North Korea – where there is so much suffering but also glimpses of hope – and perhaps even glimpses of Tolkien’s “final victory.” In September I travelled to Seoul, North East China and to the border with North Korea at the River Tumen, where escaping refugees are regularly shot dead.

North Korea spent $800 million launching a missile while people go without food – and shoot to kill refugees at the River Tumen

On a visit to North Korea I had a surreal experience as my Air China plane touched down at Pyongyang airport the music which was played into the passenger cabin was Isaac Watts’ Christmas carol “Joy To The World”:

Joy to the World, the Lord is come!

Let earth receive her King;

Let every heart prepare Him room;

And let Heaven and nature sing.”

For North Korea may that be so.

In singing our Christmas carols and offering our Christmas Masses, remembering broken people, and the burdened donkey, we must hold this joy in our hearts knowing what the Christmas story represents and knowing with confidence how the story will end.

————

2015 – Pray for North Korea this Christmas:

Christmas Reflection

Christmas again – and in a remote corner of the Roman empire a boy who changes the world is born in a manger; a boy who will never become a ruler, who never owned a car or a mansion, who never ran for high political office, never become a celebrity or rose to be a man of great wealth or rank.

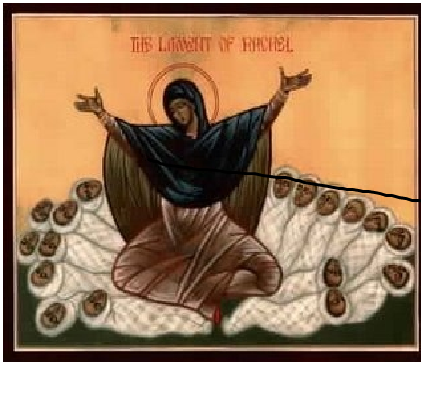

Yet, the birth of this boy, who, other than the clothes stripped from His body and divided among His torturers, will leave no earthly possessions behind Him and be buried in another man’s grave, strikes such fear into the mind of Herod the King that a genocide of young children is ordered.

In unleashing this horrific wave of persecution thousands of other young boys, under the age of two, are murdered. To escape the massacre the child in the manger is secreted away in the dead of night to a place of safety in far away Egypt.

In the midst of the shopping frenzy and consumerism which marks out our contemporary Christmas it’s worth pondering these extraordinary events.

In the whirly-gig of preparations for the great festival we not only overlook the awesome religious significance of the manger moment – when “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us” – but we overlook the brutality and violence which accompanies the new Adam at his Bethlehem nativity.

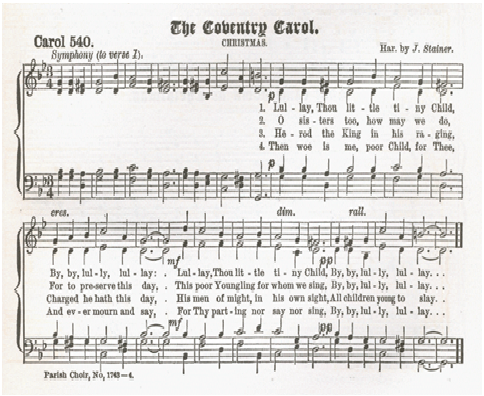

It is a sobering thought that, even as those near magical and enchanted moments are being enacted, when the shepherds and the Magi kneel before Him and worship God, Herod’s ruthless butchers are sharpening and making ready their knives. In the words of the sixteenth century Coventry Carol:

“Herod, the king, in his raging,

Charged he hath this day

His men of might, in his own sight,

All young children to slay.”

This lament of a mother for her child doomed to die are lyrics with applicability to our own times.

Written by Robert Croo, in 1534, for the traditional Coventry Plays and included in The Pageant of the Shearman and Tailors Guild, which depicted Herod’s slaughter of the innocents, the lyrics could so easily be the lament of mothers caught up in contemporary tragedy across the globe.

Whether it is the child caught in the cross fire of a Sudanese militia; the young girl raped by a Congolese war lord; the Ugandan child murdered in a pagan ritual of child sacrifice; the child enlisted to be a child soldier or a drugs runner ; the boy or girl who is trafficked, exploited, robbed of innocence or abused; the child who each year joins the 100,000 UK runaways; or the baby, sheltering in what should be the safest place on earth – their mother’s womb – we feel all too keenly the caroler’s lament:

“Then woe is me, poor Child, for Thee,

And ever mourn and say;

For Thy parting, nor say nor sing,

By, by, lullay, lullay.”

The boy in the manger represents all persecuted people. His acute vulnerability challenges us to take a stand against the destruction of life and to pit ourselves against today’s Herods and their contemporary crimes against humanity. This story tells us everything we need to know about how to live – but it also teaches us about how to face everyday crises and about the reality of evil.

This is the challenging story of a young man and woman caught up in a bewildering drama – but who remain faithful to one another and who cherish a new life; it is the story of a man who stands by a woman unexpectedly with a child that isn’t his; it’s the story of a boy born in a manger swaddled in poverty; the refugee’s story of a forced escape; the story of a tyrant with a blood lust; and it is a story lived out against the threatening drum beat of arrest, escape, vilification and persecution. It’s a story that will end on Calvary and triumphantly in an empty tomb.

Although, for the shepherds and the Magi, this is a story which represents a dream come true, for me it remains a story of great crisis. It is the story which can propel us into searching and discovering the very purpose for which we have been made.

We must never let it be muffled by the sentimentalism, rank commercialisation, and forced conviviality into which Christmas celebrations can degenerate.

In “The God In The Cave” G.K.Chesterton, whose greatest love was the celebration of the Christmas festival, reminds us that if we begin the search it will not be without its risks, that evil hovers over the crib scene, stalking Jesus and His family:

“There was present in the primary scenes of the drama that Enemy that had rotted the legends with lust and frozen the theories into atheism, but which answered the direct challenge with something of that more direct method which we have seen in the conscious cult of the demons.”

Chesterton tells us that these stirrings of evil have a particular “detestation of innocence”.

Herod, he says, “seems in that hour to have felt stirring within him the spirit of strange things… Everyone knows the story; but not everyone has perhaps noted its place in the story of the strange religions of men… a seer might perhaps have seen something like a great grey ghost that looked over his shoulder…The demons in that first festival of Christmas, feasted also in their own fashion.”

Chief among our modern conceits is to foolishly dismiss the presence of evil.

So, let’s celebrate as we welcome again the child into our midst, but never overlook the presence of Chesterton’s grey ghosts.

May you and those you love have a joyous and happy Christmas

![Chesterton[1]](https://www.davidalton.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/chesterton11.jpg)