Freedom of Religion and Belief

Motion to Take Note

Watch the debate at:

http://parliamentlive.tv/event/index/53d07cde-20ee-4f53-80d3-f4c075deb3d0?in=16:20:35

4.20 pm

Moved by Lord Alton of Liverpool

To move that this House takes note of worldwide violations of Article 18 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the case for greater priority to be given by the United Kingdom and the international community to upholding freedom of religion and belief.

Lord Alton of Liverpool (CB): My Lords, I begin by thanking all noble Lords who take part in today’s debate. We have a speakers list of great distinction, underlining the importance of this subject. It is also a debate that will see the valedictory speech of the right reverend Prelate the Bishop of Leicester, who has given such distinguished service to your Lordships’ House. The backdrop to all our speeches is Article 18, one of the 30 articles of the 1948 Declaration of Human Rights. It insists:

“Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance”.

The declaration’s stated objective was to realise,

“a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations”.

However, with the passage of time, the declaration has acquired a normative character within general international law. Eleanor Roosevelt, the formidable

chairman of the drafting committee, argued that freedom of religion was one of the four essential freedoms of mankind. In her words:

“Religious freedom cannot just mean Protestant freedom; it must be freedom of all religious people”,

and she rejoiced in having friends from all faiths and all races.

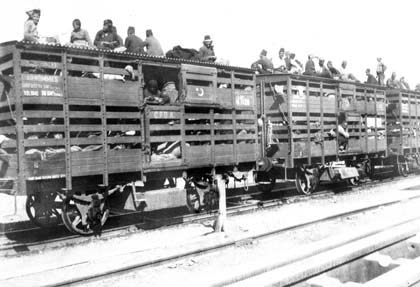

Article 18 emerged from the infamies of the 20th century—from the Armenian genocide to the defining depredations of Stalin’s gulags and Hitler’s concentration camps; from the pestilential nature of persecution, demonisation, scapegoating and hateful prejudice; and, notwithstanding violence associated with religion, it emerged from ideology, nation and race. It was the bloodiest century in human history with the loss of 100 million lives.

The four great murderers of the 20th century—Mao, Stalin, Hitler and Pol Pot—were united by their hatred of religious faith. Seventy years later, all over the world, from North Korea to Syria, Article 18 is honoured daily in its breach, evident in new concentration camps, abductions, rape, imprisonment, persecution, public flogging, mass murder, beheadings and the mass displacement of millions of people. Not surprisingly, the All-Party Group on International Freedom of Religion or Belief, in the title of its influential report, described Article 18 as “an orphaned right”. A Pew Research Center study begun a decade ago found that of the 185 nations studied, religious repression was recorded in 151 of them.

Today’s debate, then, is a moment to encourage Governments to reclaim their patrimony of Article 18; to argue that it be given greater political and diplomatic priority; to insist on the importance of religious literacy as a competence; to discuss the crossover between freedom of religion and belief and a nation’s prosperity and stability; and to reflect on the suffering of those denied this foundational freedom.

Although Christians are persecuted in every country where there are violations of Article 18—from Syria and Iraq, to Sudan, Pakistan, Eritrea, Nigeria, Egypt, Iran, North Korea and many other countries—Muslims, and others, suffer too, especially in the religious wars raging between Sunnis and Shias, so reminiscent of 17th-century Europe. But it does not end there. In a village in Burma, I saw first-hand a mosque that had been set on fire the night before. Muslim villagers had been driven from a village where for generations they had lived alongside their Buddhist neighbours. Now Burma proposes to restrict interfaith marriage and religious conversions. It is, however, a region in which Christian Solidarity Worldwide and the Foreign and Commonwealth are doing some excellent work with lawyers and other civil society actors, promoting Article 18.

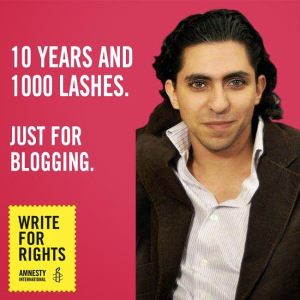

Think, too, of those who have no religious belief, such as Raif Badawi, the Saudi Arabian atheist and blogger sentenced to 1,000 public lashes for publicly expressing his atheism. That has been condemned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights as,

“a form of cruel and inhuman punishment”.

Alexander Aan was imprisoned in Indonesia for two years after saying he did not believe in God. Noble Lords should recall that Article 18 is also about the right not to believe.

Later, we will hear from the most reverend Primate the Archbishop of Canterbury, who recently said that the “most common feature” of Anglicanism worldwide is that of being persecuted. Twenty-four of the 37 Anglican provinces are in conflict or post-conflict areas. Referring to the 150 Kenyan Christians who were killed on Maundy Thursday, the most reverend Primate said:

“There have been so many martyrs in the last year … They are witnesses, unwilling, unjustly, wickedly, and they are martyrs in both senses of the word”.

We will also hear from my noble friend Lord Sacks, who offered his prayer on Hanukkah last year for,

“people of all faiths working together for the freedom of all faiths”.

My noble friend’s brilliant critique, Not in God’s Name: Confronting Religious Violence, is required reading for anyone trying to comprehend what motivates people to kill Christian students in Kenya, Shia Muslims praying in a mosque in Kuwait, Pakistani Anglicans celebrating the Eucharist in Peshawar or British tourists simply holidaying in Tunisia and for anyone trying to understand the dramatic rise in Christian persecution, the vilification of Islam in some parts of the world and, in Europe, the troubling reawakening of anti-Semitism.

My noble friend’s insights into the shared stories of the Abrahamic faiths—not least the displacement stories of Isaac and Ishmael, Jacob and Esau, Leah and Rachel, and Joseph and his brothers—and how they can be used to promote mutual respect, coexistence, reconciliation and the healing of history underline the urgent need for scholars from those faiths to combat the evil being committed in God’s name and to give emphasis to the ancient texts in a way which upholds the dignity of difference—the title of another of my noble friend’s books. If Jews, Muslims and Christians are no longer to see one another as an existential threat, we urgently need a persuasive new narrative, which is capable of forestalling the unceasing incitements to hatred which pour forth from the internet and which capture unformed minds.

It is not just scholars but the media and policymakers who need greater religious literacy and different priorities. How right the BBC’s courageous chief international correspondent, Lyse Doucet, is when she says:

“If you don’t understand religion—including the abuse of religion—it’s becoming ever harder to understand our world”.

It is increasingly obvious that liberal democracy simply does not understand the power of the forces that oppose it or how best to counter them. At best, the upholding of Article 18 seems to have Cinderella status. During the Queen’s Speech debate, I cited a reply to Tim Farron MP—for whom this has been quite a notable day—in which Ministers said that the Foreign Office,

“has one full time Desk Officer wholly dedicated to Freedom of Religion or Belief”.

“the Head and the Deputy Head of HRDD spend approximately 5% and 20% respectively of their time on FoRB issues”.

To rectify this, will we prioritise Article 18 in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office business plan and across government departments? Has the FCO considered convening an international conference on Article 18—something I have raised with her? Is it an issue we will raise at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Malta in November?

In May, the Labour Party gave a welcome manifesto commitment to appoint a Canadian-style special envoy to promote Article 18. The Foreign Office resists this, insisting that all our diplomats promote freedom of religion and belief. But that has not been my experience. On returning to Istanbul from a visit to a 1,900 year-old Syrian Orthodox community in Tur Abdin, which was literally under siege, I was told by our UK representative that his role was to represent Britain’s commercial and security interests and that religious freedom was a domestic matter in which he did not want to become involved. Self-evidently, there is a direct connection with our security interests, not least with millions of displaced refugees and migrants now fleeing religious persecution.

Paradoxically, if he had studied the empirical research on the crossover between freedom of religion and belief, and a nation’s stability and prosperity, he might have come to a very different conclusion. Where Article 18 is trampled on, the reverse is also true, as a cursory examination of the hobbled economies of countries such as North Korea and Eritrea immediately reveals. This is not a marginal concern, as the outstanding briefing material for our debate from many human rights organisations makes clear.

Last month, the noble Baroness, Lady Berridge, and I chaired the launch of a report by Human Rights Without Frontiers. Among its catalogue of egregious and serious violations, it says that North Korea, China and Iran had the highest number of people imprisoned, in their thousands, for their religion or belief. It highlights Pakistan, where in 2011 two politicians who questioned the blasphemy laws were shot dead; where Asia Bibi remains imprisoned with four other Christians and nine non-Christians, facing the death sentence for alleged blasphemy; and where Shias and Ahmadis have faced ferocious deadly attacks.

When did we last raise these cases and other abuses of Article 18 with Pakistan, or the use of blasphemy laws in Sudan, where two pastors are currently on trial, facing charges that carry the death sentence? Have we urged Sudan to drop the charges against 10 young female Christian students who face up to 40 lashes because of the clothes they were wearing? What of the Chinese Christian lawyers arrested this week as part of a major crackdown? Will Article 18 be on the agenda for discussion with China’s President when he visits the United Kingdom?

I am a trustee of the charity Aid to the Church in Need, and the noble Baroness the Minister kindly launched its report, Religious Freedom in the World 2014, which found that religious freedom had deteriorated in almost half the countries of the world, with sectarian violence at a six-year high, nowhere more so than in the Middle East, where last week Pope Francis said that Christians are subject to genocide. In a recorded

message for that launch, His Royal Highness the Princes of Wales condemned “horrendous and heart-breaking” persecution, and spoke of his anguish at the plight of Christianity in the Middle East, in the region of its birth, describing events in Syria and Iraq as an “indescribable tragedy”.

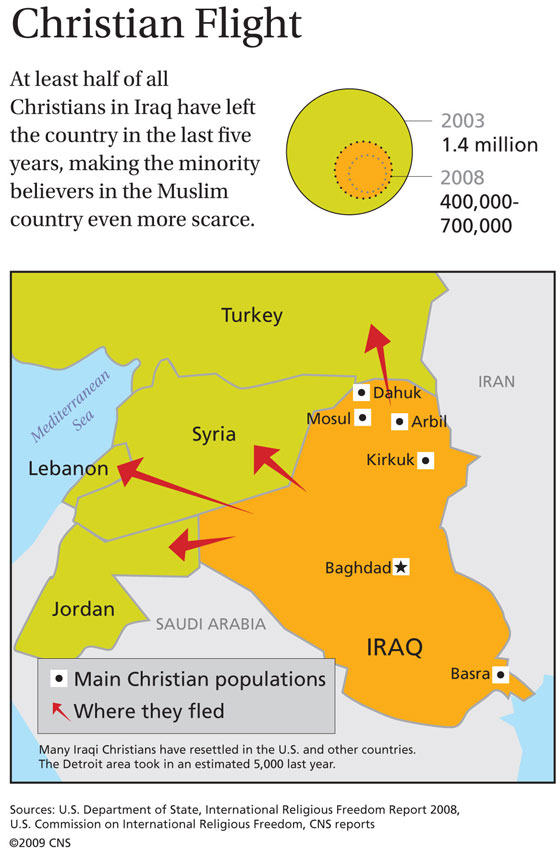

In 1914, Christians made up a quarter of that region’s population. Now they are less than 5%. Archbishop Bashar Warda of Irbil, during a meeting that I chaired here in the House, underlined their traumatic, degrading and inhuman treatment, pleading with the international community to provide protection. Two weeks ago the same plea was made by a remarkable Yazidi woman who gave evidence at a meeting organised by the noble Baroness, Lady Nicholson. The Yazidi, a former Iraqi Member of Parliament, told us:

“The Yazidi people are going through mass murder. The objective is their annihilation. 3000 Yazidi girls are still in D’aesh hands, suffering rape and abuse. 500 young children have been captured, being trained as killing machines, to fight their own people. This is a genocide and the international community should say so”.

This view has been reinforced this week by reports on “Newsnight” and “Dispatches”. How will we answer that woman? Do we intend to use our voice in the Security Council on behalf of the Yazidis and Assyrian Christians? Do we intend to have the perpetrators brought to justice in the ICC? Are we collating and documenting every instance, from genocide and rape to the abduction of bishops and priests, to the burning of churches and mosques, to the beheading of Eritrean Christians and Egyptian Copts by ISIS in Libya? What are we doing to create safe havens where these minorities might be protected?

In 1933, Franz Werfel published a novel, The Forty Days of Musa Dagh, based on a true story about the Armenian genocide. His books were burnt by the Nazis, no doubt to try to erase humanity’s memory, Hitler having famously asked, “Who now remembers the Armenians?”. The Armenian deportations and genocide claimed the lives of an estimated 1.5 million Armenian Christians. Werfel tells the story of several thousand Christians who took refuge on the mountain of Musa Dagh. The intervention of the French navy led to their dramatic rescue.

A hundred years later, the Yazidis besieged on Mount Sinjar were saved, but their lives are still in the balance. Last week the Belgians made it to Aleppo and brought 200 Yazdis and Christians to safety. For fragile communities facing a perilous future, such as these, could we not do the same? Are we re-examining our asylum rules to reflect the lethal threats faced by families and individuals fleeing their native homelands?

In the longer term, should not the international community have a more consistent approach to Article 18? We denounce some countries while appeasing others who directly enable jihad through financial support or the sale of arms. Western powers are seen as hypocrites when our business interests determine how offended we are by gross human rights abuses. Take Saudi Arabia as one example.

The challenge is vigorously to promote Article 18 through our interventions and our aid programmes, unceasingly countering a fundamentalism that promotes hatred of difference and persecutes those who hold

different beliefs. For the future, the three Abrahamic religions and Governments need to recapture the idealism of Eleanor Roosevelt, who described the 1948 declaration as,

“the international Magna Carta for all mankind”.

She said that Article 18 freedoms were to be one of the four essential freedoms of mankind. Who can doubt that this essential freedom needs to be given far greater emphasis and priority in these troubled times? I beg to move.

4.35 pm

Lord Mackay of Clashfern (Con): My Lords, I congratulate the noble Lord, Lord Alton, on obtaining this debate, on the eloquent way in which he introduced it and on the tremendous illustrations that he gave of how bad the situation is throughout the world. I do not have the qualifications to follow him, and certainly do not have the qualifications to be in front of many leaders in this debate, but here I am, and I shall try to make the best of it. I also wish to express my deep gratitude to Edward Scott of our Library for the excellent brief he prepared for this debate, which shows the position in great and excruciating detail. I am sure that anyone who has read it will feel tremendous sympathy and a loathing for what is happening to so many of our fellow humans throughout the world for the simple reason that they have adopted a faith or belief, including a non-faith—no belief at all, which is also protected—in the execution of their ordinary lives and have been tremendously badly dealt with on that account.

I declare my interest as a professing Christian for most of my life, and a practising Christian so far as I can. I am sorry to say that I have not reached the extent of perfection in that area which I would have liked. I am glad that the right reverend Prelate the Bishop of Leicester is speaking in this debate, although I am very sorry that it will be a valedictory speech. He has given most distinguished service in this House and also in his diocese in an area where there is a great deal of difference and, I hope, also the dignity of difference in ethnic and other communities. I wish him well in his retirement.

Speaking from the government Dispatch Box when she was a Minister in the Home Office, the noble and learned Baroness, Lady Scotland of Asthal, expressed the view that her religion defined her personality. This shows that the restriction of a person’s faith or belief is as serious as any other restriction of personal freedom. The brief to which I have referred and the speech of the noble Lord, Lord Alton, show that mistreatment for faith and belief throughout the world extends to much more than restriction of bodily movement. It goes to serious injury and death in the most terrible circumstances.

Yesterday we had outside the House a demonstration relating to prisoners of conscience. This is a most important aspect of the human personality—the internal monitor which tells us that what we are doing is wrong, even when no human eye can see us, and whether or not what we are doing is in according with the tenets of the faith, belief or non-belief we seek to follow.

In preserving standards in society, listening to conscience is an extremely effective activity. More so even than an effective enforcement system, it can preserve society’s standards. It was valued in our nation during two world wars. Persons with a conscientious objection to military service were exempted from the universal obligation to enlist. It was also shown in relation to the Abortion Act.

Charities based on faith have done tremendous service in many nations throughout the world. It surely is the most terrible damage to a nation’s people that they are debarred from having these services simply on the ground of the faith of the organisation that is providing them. In our own country, we had the problem of the Catholic adoption agencies that were providing an excellent service but which were debarred from continuing to do so because they were not able to offer as full a service as some would have required.

I am sure that leading by example is one important way to contribute in trying to help with this tremendous problem. I am sure there are many other ways, which will be illustrated by the distinguished speakers to follow.

4.41 pm

Lord McFall of Alcluith (Lab): My Lords, it is a privilege to participate in this debate and I congratulate the noble Lord, Lord Alton, on securing it, as well as on the work that he and the noble Baroness, Lady Berridge, have done over many months and years on this issue.

As we know, Article 18 is under threat in over a quarter of the nations in the world. The noble Lord, Lord Alton, has given eloquent testimony to what is happening. I want, however, to focus on the domestic—on us. To change the world, first we have to change ourselves. When the most reverend Primate the Archbishop of Canterbury took office, he said that one of his three principles was the concept of good disagreement. That is a very important concept for us.

As I remember from my childhood in Scotland, the society had been scarred by what the noble Lord, Lord Sacks, has referred to as sibling rivalry—bigoted, religious, sibling rivalry. In 1923, the Church and Nation Committee of the Church of Scotland asked for Irish immigrants to be repatriated. More specifically, it was Catholic Irish immigrants, like my forebears. So if good people had not got together and ensured that that crusade failed, I, for one, would probably not be here today. It was good people walking together. There is still a legacy in Scotland; we have to recognise that sectarianism has not departed. Our own experiences should teach us a lot.

As the noble Lord, Lord Sacks, said in his book, which makes compelling reading, we need faith to strengthen, not to dampen, our shared humanity. He made it very clear, as we all know, that it will be soft power that wins this battle—if we can call it a battle. It will not be hard power. War is won by weapons, but dialogue wins the peace.

I am delighted to see not only the noble Lord, Lord Sacks, but also the noble Lord, Lord Singh, and the right reverend Prelate the Bishop of Leicester who

have contributed greatly to the dialogue. It is a dialogue with strangers. The biblio-patriarch Abraham has been referred to. Abraham’s test of worthiness, as we know, is the question, “Did you show kindness to strangers?”. Abraham ruled no empire, he commanded no army, he conquered no territory, but today he is revered by 2.5 billion Christians, 1.6 billion Muslims, and 13 million Jews. The Abrahamic faiths and others need to walk much closer together.

That is very hard to envisage today, but we can look back at our short history to see that there have been successes. With Vatican II in the 1960s, Pope John XXIII, in his encyclical Nostra Aetate, transformed the relationship between Catholics and Jews, and 2,000 years of pain and sorrow were diluted as a result of that engagement. That prompts the question: can the world be changed? If the Christian and Jewish relationship can be changed, can the Christian, Jewish, Islamic, Sikh and non-faith relationships be changed as well? Pope Francis’s latest encyclical, Laudato Si’, is an encouraging example because he embraces all humankind. He makes a call in the very first paragraph of the encyclical for care for our common earthly home. He says:

“Nothing in this world is indifferent to us”.

For a very short time in the Labour Government I had the privilege of being Minister for Northern Ireland. I saw examples in the peace process in Northern Ireland, but I shall illustrate just two examples today. The first is Gordon Wilson, whose daughter was killed in the Enniskillen Remembrance Day bomb. He had to hold her hand while she was dying and she said that she loved him. Immediately after that, he came out and said:

“I bear no ill will. I bear no grudge … I will pray for these men tonight and every night”.

The other example that I remember was Father Alec Reid, the late Redemptorist priest from Clonard monastery in Belfast, who was a silent architect of the peace process because he allowed Gerry Adams, John Hume and others to come together to ensure that there was a dialogue and an understanding there. The photograph of Father Reid giving the last rites to soldier David Howes, when he and another colleague ran into a republican funeral, is one that will stay with us.

That is an example of the good of two individuals confronting the evils of terrorism. In a 20th-century world dominated by violence and mayhem in the name of religion, our task, perhaps akin to the task of the miracle of the loaves and fishes in the Bible, is to multiply that number, not 1 millionfold or 10 millionfold but 100 millionfold. Eighteenth-century author Jonathan Swift’s statement is maybe as relevant today, and something for us to remember:

“We have just enough religion to make us hate, but not enough to make us love one another”.

As we go on our journey together, it is worth remembering that.

The Earl of Courtown (Con): My Lords, I apologise for interrupting the debate for a few moments, but I ask noble Lords to remember that it is time-limited to five minutes per speaker. Once the clock reaches five, your Lordships are out of time.

Lord Thomas of Swynnerton (CB): My Lords, it may be appropriate—

Lord Thomas of Swynnerton: It is the turn of the Cross Benches.

The Earl of Courtown: Order. There is a speakers list for this debate.

4.48 pm

Lord Avebury (LD): My Lords, I join in the congratulations that have been expressed to my noble friend Lord Alton for the powerful way in which he introduced this debate, and indeed for the consistent and wonderful way in which he always defends the rights of people’s religious freedom. On no occasion have I heard him speak more powerfully on the subject than he did today.

My old friend Dennis Wrigley, founder of the Maranatha community, asks if we care that entire Christian communities have been wiped out in the Middle East and what we are prepared to do about it. Those are questions that I hope the Minister will be able to answer.

However, the challenge is in fact much greater than that. Daesh makes no secret of its intention to expand its so-called caliphate from its base in Syria and Iraq so that it covers the rest of the Middle East and north Africa. Ultimately it aims to spread its interpretation of seventh-century Islamic governance and beliefs across the whole world, eliminating all other faiths by conversion or assassination, as it has already demonstrated by the massacres of Yazidis, Christians and Shia and the enslavement of the martyrs’ widows in the territory that it occupies.

William Young of the RAND Corporation observed:

“Al-Baghdadi’s messages have resonated with Sunnis in the region, North Africa, Europe and the United States primarily because he appears successful”.

“The faster the Muslim world can be shown that ISIS is not invincible and does not have a divine mandate to rule the Islamic world, the quicker young Muslims and others will stop listening to its messaging”.

The coalition needs to ratchet up military operations against the Daesh and we should explore the willingness of our partners in the 60-state coalition to provide troops for a multinational ground force in Syria. We are providing 75 military instructors and headquarters staff as part of the US-led programme to support the “moderate Syrian opposition”. Can the Minister please identity the groups included in that phrase. They do not include, apparently, the heroic YPG which successfully repelled the Daesh assault on Kobane at the end of last year. Operations on that frontier would have the merit of not undermining the Assad Government’s capacity to hold the Daesh at bay.

The so-called caliphate sends out a powerful signal to extremist Sunni Muslims elsewhere that they can help towards the realisation of the universal Islamic state by destabilising existing kufr Governments through acts of indiscriminate terrorism such as the attack on British tourists in Tunisia. However, the main thrust of Daesh operations this year outside its own territory

has been attacks against the soft target of Shia mosques in neighbouring Arab countries. In March there were simultaneous attacks on two mosques in Sanaa, capital of Yemen, killing 137 people and injuring 357. In May there were two attacks on Shia mosques in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia, killing 29 and injuring more than 85; and on 2 June, a Shia mosque in Kuwait was attacked, killing at least 27 and injuring 227 others.

However, it goes wider than that. In Pakistan, terrorist groups swearing allegiance to the Daesh have been responsible for three major atrocities so far this year: the suicide bombing of an imambargah at Shikarpur in January, which killed 80 and injured 100; a suicide attack on a Shia mosque in Peshawar, capital of troubled Balochistan, in February, killing a least 22 and injuring 80 at Friday prayers; and a gun attack by killers on motorcycles on a bus carrying Ismailis in Karachi in May, killing at least 26 and injuring 13. Eliminating the Daesh, its metastases and its wicked ideology taught in Saudi-funded madrassahs throughout the world must be the main goal of all who believe in freedom of religion.

4.53 pm

The Archbishop of Canterbury: My Lords, I am grateful to have the opportunity to speak in the debate and I thank the noble Lord, Lord Alton, for securing it and for all the work he has undertaken in this area over many years. I associate myself very closely with what he said in his very eloquent opening speech and also with the speeches of the noble and learned Lord, Lord Mackay, and the noble Lord, Lord McFall. I also pay tribute to the right reverend Prelate the Bishop of Leicester. He will be much missed by this House and I will miss him enormously for the wise advice he has given me on numerous occasions.

We have already heard many examples of the horrific situations around the world where people are persecuted for their religion or for their absence of religion. I witnessed such persecution in its rawest form many times during my visits in 2013 and 2014 to the 37 other provinces of the Anglican communion. Almost half of these provinces are living under persecution; they fear for their lives every day.

I will make two points in the short time available in this debate The first is that the relationship between law and religion is invariably a delicate one. The passionately lived religious life or passionately lived humanist life of many people around the world and in this country cannot be compartmentalised within our legal and political systems. It is not good enough to say that religion is free within the law. As was eloquently pointed out by the noble and learned Lord, Lord Mackay, religion defines us—it is the fundamental element of who and what we are. Thus, religious freedom and the freedom not to have a religion stands beneath the law, supporting it and creating the circumstances in which you can have effective law, as has been the case in this country since the sealing of Magna Carta 800 years ago, negotiated by my predecessor Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton. In its first clause, it says that,

“the English Church shall be free, and shall have its rights undiminished, and its liberties unimpaired”—

sorry, I had better declare an interest there.

Religion gave birth to the rule of law, particularly through Judaism. The question is therefore: how do we translate this undiminished right and unimpaired liberty into the contemporary situation, where, too often, as we heard from the noble Lord, Lord Alton, culture, law and religion seem to have incommensurable values? The foundational freedom of religious freedom in the state prevents the state claiming the ultimate loyalty in every area, a loyalty to which it has no right—never has done and never will do—if we believe in the ultimate dignity of the human being.

My second point is that religious freedom is threatened on a global scale, as we have heard, but also in a very complex way. Attacks on religious freedom are often linked to economic circumstances, to sociology, to history and to many other factors. Practically, if we are to defend religious liberty, we have to draw in these other factors. For example, if we want to defend religious freedom around the world—and again I say, the freedom to have no religion—do not sell guns to people who oppress religious freedom; do not launder their money; restrict trade with them; confine the way in which we deal with them; and, above, all, speak frankly and openly, naming them for what they are.

Where a state claims the ultimate right to oppress religious freedom, it stops the last and the strongest barrier against tyranny. From the beginning of time—from the beginning of the Christian era, when the apostles said that they would obey God rather than the Sanhedrin, through the Reformation to the martyrs of communism, to Bonhoeffer and to Archbishop Tutu—up to our own day around the world, we have needed religious freedom as a global defence of freedom.

4.58 pm

Baroness Berridge (Con): My Lords, I, too, congratulate the noble Lord, Lord Alton, on his uncanny knack of being successful in the ballot for debates.

I join the most reverend Primate in celebrating Magna Carta, which opens with,

“the English Church shall be free”,

meaning from state intervention, which at that time of course meant the king. Freedom of religion or belief, as set out in Article 18, is another deeply constitutional statement. As the UN special rapporteur illustrated in his comment to me, “There is lots of religion in Vietnam but not a lot of it is free”. The declaration is founded on individuals enjoying human rights when the state knows how to behave, knows its own limits and understands its role as protector of its citizens’ human rights from violation by third parties. In old communist states such as Vietnam, religion is controlled by the state, but another common backdrop to many Article 18 violations is an inappropriate connection between a religious institution or a faith or a stream of one faith, and the state. Often, that institution or faith has such preference that pluralism is suffocated, and, in the extreme, a religion becomes identified with nationality. Is Myanmar’s identity becoming synonymous with being Buddhist? The Rohinga Muslims are denied citizenship and an outcry by Buddhist extremists led the Government to capitulate and confiscate their only identity document.

I am intrigued that Her Majesty’s Government can exhibit the FCO priority of freedom of religion and belief in our newly opened visa office in Rangoon. I expect my noble friend will have to write to me on this, but how is the United Kingdom able to offer UK visas, regardless of religion, when Rohinga Muslims have no documentation? Is it only wealthy Buddhist tourists or business men—not Muslims or Christians—who can come to the UK? The Rohingans were disenfranchised in this year’s election. It is also proposed that half a million refugees from the Central African Republic, 90% of whom are Muslim, be denied their voting rights. What representations have Her Majesty’s Government made to the CAR’s interim Government? Will this not increase the risk of refugees who are languishing in Chad being recruited to IS, which is already recruiting from neighbouring Sudan?

The trajectory on this issue has spiralled. However, I highlight Vietnam, Myanmar and CAR because they are in, I believe, the doable category. In 2006 Vietnam was removed, with American pressure, from the list of countries of particular concern, but has now fallen back. The UN special rapporteur visited in 2014 and found serious Article 18 violations and,

“credible information that some individuals whom I wanted to meet with had been either under heavy surveillance, warned, intimidated, harassed or prevented from travelling by the police”.

The Human Rights Watch report, Persecuting “Evil Way” Religion, details state persecution of central highland Christians, many of whom have fled to Cambodia. Cambodia refuses to allow them to claim asylum and returns them, rather like China does to those who escape North Korea. Will the Minister please make representations to Cambodia to allow the UN to process refugees there, if it is unwilling to comply with its international obligations?

It might also be worth mentioning how discerning the UK customer can be and how sensitive brands like Marks & Spencer can be when they source from many manufacturers in Vietnam and Cambodia.

The digital revolution could create further Article 18 violations. According to a report in the Economist, by 2020 80% of adults will have a smartphone that is able to receive different religious messages that state or religious leaders will scarcely be able to control. Will many more people start switching faith, challenging existing political and religious power structures?

We should also keep a close eye on what is happening under the new Government of India. We do not want to add into this space a rise of Hindu militancy which is semi-connected to identity, and to see the persecution of a large number of Muslims and Christians.

Who knows what the future holds? Many Governments, parliamentarians, religious leaders and royalty have, however, grasped the Article 18 issue, and the Pope’s celebrity status at the UN General Assembly in September is incredibly timely. The missing players—consumers and businesses—need to enter the stage, and it looks as if Brazil, at the Olympics, will be introducing the Global Business & Interfaith Understanding Awards, which they hope to become part of the Games. However, if by 2020 violations have flat-lined, that will indeed be an achievement.

5.03 pm

Lord Singh of Wimbledon (CB): My Lords, I too pay tribute to the noble Lord, Lord Alton, for securing this important debate, and for his sterling work in putting concern for human rights high on the agenda of this House.

Article 18 of the 1948 UN declaration is unambiguous in its guarantee of freedom of religion and belief. Yet we live in a world where those rights are all too frequently ignored. We have been recently remembering the horror of Srebrenica, where, 20 years ago, 8,000 Muslim men and boys were rounded up by Serb forces and ruthlessly murdered simply because they were Muslims. Last year Sikhs commemorated the 30th anniversary of the brutal murder of thousands of Sikhs in India, simply for being Sikhs. The Middle East has become a cauldron of religious intolerance and unbelievable barbarity. The number of Christians has dwindled alarmingly. We hear daily of thousands fleeing religious persecution in leaky, overcrowded boats, with little food or water.

Where have we gone wrong? In commerce or industry, if a clearly desirable idea or initiative fails again and again, it goes back to the drawing board. Today we need to ask ourselves: why is there widespread abuse of the right to freedom of belief? This important right, like all others embedded in the UN declaration, needs the total commitment of countries with political clout to make it a reality. Unfortunately, even permanent members of the Security Council frequently put trade and political alliances with countries with appalling human rights records above a commitment to human rights. There are many examples, but time permits me to mention only a couple relating to our own country.

During the visit of a Chinese trade delegation in June last year, a government Minister said that we should not allow human rights abuses to “get in the way” of trade. His statement, undermining the UN declaration, went virtually unchallenged. At about the same time, we had a Statement in your Lordships’ House that the Government were pressing for a UN-led inquiry into human rights abuse in Sri Lanka. Fine, but when I asked whether the Government would also support a similar inquiry into the mass killing of Sikhs in India—yes, I know it is a much bigger trading partner—I received a brusque reply that that was a matter for the Indian Government.

I have asked on five occasions the question why the UK Government regard the systematic killing of Sikhs in India as being of no concern to the United Kingdom, only to get the same dismissive non-response. I ask it again today, and hope that noble Lords and Britain’s 500,000 Sikhs will get the courtesy of a proper, considered reply. The great human rights activist, Andrei Sakharov, said that we must be even-handed in looking at human rights abuse. If our country—one of the most enlightened in the world—puts trade above human rights, it is easy to understand why other countries turn a blind eye to rights such as freedom of belief. It is a right so central in Sikhism that our ninth guru, Guru Tegh Bahadur, gave his life defending the right of Hindus—a different religion from his own—against forced conversion by the then Mughal rulers.

We can list human rights abuse for ever and a day without making a jot of difference if we and other great powers continue to put trade and power bloc politics above human rights. We start each day in this House with Prayers to remind us to act in accord with Christ’s teachings. He, like Guru Nanak, reminded us never to put material gain before concern for our fellow beings. We need to act on such far-sighted advice.

I look forward to hearing my friend, the right reverend Prelate the Bishop of Leicester, and wish him well in his retirement.

5.08 pm

The Lord Bishop of Leicester (Valedictory Speech): My Lords, I want to add my thanks to that of so many others to the noble Lord, Lord Alton, for bringing this matter before us, not least as it provides me with an opportunity to make a final speech to your Lordships’ House on a matter of such overwhelming importance.

My retirement, I am delighted to say, will in some small way enhance religious freedom in this House by providing a seat for the first female Lord Spiritual in history to occupy this Bench in the autumn. It is especially good to be following the noble Lord, Lord Singh, whose contributions here testify to the commitment of this House to religious freedom in so many ways.

The spread of global religious revival in the 21st century is described by Mickelthwait and Wooldridge in their book God is Back. They argue that it is fuelled by market competition and a customer-driven approach to salvation. In the five years since its publication, they could not have imagined how those principles would mutate into the present appalling world crisis, so vividly described by so many speakers. The challenge to religious freedoms derives in part from treating faith as a consumer preference rather than the most profound definition of what it is to be human.

In my 16 years as Bishop of Leicester, we have learned much about the principles and practice of religious freedom and the way it shapes the deepest contours of the human psyche. As well as having local applications, that also has international implications. The first principle is that it is not enough simply to defend religious freedom; it has to be positively exercised in ways that encourage others to embrace it. It involves drawing on the spiritual resources of faith to unlock the best in others, to speak on behalf of the voiceless and to create community. When a young Nigerian Christian was murdered in Highfields in Leicester two years ago, there was an immediate retaliatory attack on an entirely innocent Muslim family, killed by a fire bomb on the same day. The tensions were palpable, but were eventually calmed by systematic, careful conversations and the public ritualising of grief and reconciliation on both sides.

Secondly, the principle that religious freedom is an inalienable right means that we interpret an attack on one faith as an attack on all peoples of faith. Treasuring the dignity of every human being includes treasuring the rights of others to their beliefs, especially when we disagree. That is why the Muslim leadership turned out in strength the other day at Leicester Cathedral to respect the victims of the Sousse massacre two weeks ago.

Thirdly, freedom is not a passive state. It results from the dynamic process of actively learning how others live and what they believe, and of sustained and co-operative support for each other in shared enterprises. Here, too, local practice can inform international strategy. We need to learn the best habits of face-to-face conversations with those we disagree with, especially over the big challenges of the day—climate change, poverty, conversions, gender equality and so on.

It has been an immense privilege to play a small part in the life of this House over the last 12 years and to Convene the Bishops’ Bench for six of them. It has confirmed me in the belief that the presence of the Bishops here serves rather than impedes religious freedom in countless ways. It has been rewarded with friendships, kindnesses, courtesies and opportunities far beyond my expectations or desserts. I am deeply grateful for that and even more grateful for the responsibility to think and speak carefully about how a vision of the kingdom of Jesus Christ can still shape and inform public policy today. Your Lordships’ House deserves the attention, interest and prayers of all people. It will certainly have mine in the years ahead.

5.12 pm

Lord Carey of Clifton (CB): As the noble Lord, Lord Glasman, is not able to be in the House today, it falls to me to thank the right reverend Prelate the Bishop of Leicester for his remarkable contribution over many years to this House and to wish him every success in what he goes on to do.

I join other Peers in thanking my noble friend Lord Alton for introducing this debate. As with other important human issues, he is so often the conscience of this House, and we are in his debt once more.

The freedom to think, change one’s mind, change religion, become an atheist, become a believer, and belong to tolerant and open societies is among the blessings of being a human person. Thus enshrined as Article 18 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, this great moral principle emerged from the last world war, in which millions of people were murdered because they were different. Now, 67 years later, this great article of freedom is under attack in many parts of the world.

Others have described very graphically the situation facing Christian believers and others in many different parts of the world. The recent report, Global Persecution, produced by the Maranatha community, and the report launched in November by the charity Aid to the Church in Need, Religious Freedom in the World, which my noble friend Lord Alton mentioned, describe the way minorities in the Middle East, especially Christians, are being targeted. Speaking about this in November, as my noble friend also mentioned, the Prince of Wales described Christians as being “grotesquely and barbarously assaulted” in the Middle East. Many of us are very grateful to the Prince of Wales for the stance that he has taken on religious freedom over the years. His courageous and forthright statements have won the admiration of many and he has set an example that I fervently wish our senior politicians had the boldness to emulate. But it is not just Christians that Article 18 seeks to protect. It sets forth the humanist

vision of thought: freedom for the Yazidis in Iraq, for Shia Muslims in Sunni territories and for Sunnis in Shia lands, and the freedom to embrace atheism or agnosticism, should one wish to do so.

The fact that we have to face honestly is that so much of the trouble is in countries dominated by Islam; let us get to the heart of this. Yet, in the past, Islam has flourished as a beacon of civilisation and tolerance. Indeed, one of the finest texts in the Koran states:

“There is no compulsion in religion”.

The verse is often used in interfaith contexts to show the broadmindedness of Islam. But we have to recognise that the plain meaning of that text is questioned by many Muslim scholars today. In my view—dare I say it as a non-Muslim?—this verse contains all that is necessary for Muslims to start the journey towards free, tolerant and pluralist societies. However, the rhetoric is fine but the reality is very different. It grieves me to say that there are not many Muslim-majority countries in which the freedom set out in Article 18 exists. Of course, there are Muslim countries where other faiths are tolerated but, even in those more tolerant nations, Christians cannot share their faith openly and advertise it; and Muslims cannot, with any ease, choose another faith, should they so desire.

Intolerance seems to be spreading. There has recently been a spate of church and mosque burnings in Israel, which is very disappointing as Israel has every justification for claiming to be the only democratic nation in the Middle East. Among the buildings burnt was the famous Tabgha church, which commemorates the multiplication of loaves and fishes in the gospel story.

During my time as Archbishop of Canterbury, I challenged Muslim leaders worldwide to embrace the principle of reciprocity; it remains a dream and an ideal. Here in the United Kingdom there is no barrier to belief and no restriction on believers, as long as we all behave within the breadth of British law. The ideal of reciprocity demands that people of all nations should work together to ensure that freedom to change and grow is granted to all of us, men and women alike.

5.17 pm

Baroness Howells of St Davids (Lab): My Lords, I, too, thank the noble Lord, Lord Alton, who often places a demand on this House to examine what, for believers, is God’s big idea. This debate asks us to examine an idea that was introduced by the creator, as Christians believe. The author Myles Munroe suggests that the idea is beyond the philosophical reserves of human history. The big idea appears to have germinated all religions to which humans adhere. Today we examine the big idea and ask: have we achieved it—a culture of equality, peace, unity and respect for human dignity? No, we have not.

Faith has always played a major role in the lives of individuals and institutions. It is the basis on which we build our lives and our perspective of the world. Faith is the belief that, even in the darkest of times, there is still hope to hold on to. But as our world has become

more intolerant and more hateful, the candlelight that guides believers from all denominations is being forcibly snuffed out at an alarming rate.

The deprioritisation by the international community of upholding the right to freedom of religion set out in Article 18 has had a detrimental effect on all human rights of the persecuted. Not only are they forced to worship in secret but, if caught, they can be murdered, tortured, imprisoned, beaten and even expelled from public life, including from the right to vote. According to a report by Open Doors, 100 million Christians face persecution worldwide. That is 100 million people from just one faith, having all their rights stripped away. If we show solidarity and do more to protect the rights of marginalised religious groups across the globe, I am sure we shall see an increase in respect for human rights as a whole. Can man ever be truly free if he is not allowed to have his own thoughts? If a believer can stare down the barrel of a gun and state, “My belief shall not be shaken”, we must be brave enough to stand up and say to those oppressive governments, “It is time to protect your civilians, who committed no crime but to have faith”.

However, we must lead by example as faith has long been the bones behind the laws of our country. But now the laws of our country are breaking those bones. How can we champion human rights and freedom if we do not implement Article 18 to its full extent? There has been a worrying trend emerging in British politics, a trend that is moving to oppress the freedoms of religious minorities. We say we are a Christian nation, yet there is nothing Christian in the actions of the Government in recent weeks. Article 18 can be invoked when a Government or organisation enacts a policy that unfairly impacts on minority religious groups. The two-child tax credit limit will have a distinct impact on the rights of many Catholics who, as a choice of their conscience, do not use contraception. Giving them a choice between poverty or breaking their religious code is a distinct attack on freedom of belief and conscience.

Further limitations on religious freedom have come from the heart of Westminster in a package that is supposed to suppress terrorism and protect our western values. I hope this House agrees with me that you cannot protect democracy and freedom by taking away democracy and freedom, yet that appears to be the aim of the Prevent strategy and the passing of the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015.

5.23 pm

Lord Palmer of Childs Hill (LD): My Lords, I thank the noble Lord, Lord Alton, not only for initiating the debate but preying on my conscience and encouraging me to contribute. Sadly, history shows us that religious wars and conflicts are not new. However, in modern times there has been more of an acceptance that those of different faiths and none have to get on together and at least tolerate one’s fellow man, if not necessarily love him.

We have heard and will hear from other noble Lords of repression and lack of freedoms in the current unstable world situation. As a Jew, I feel strongly about the Holocaust, which touched my own

family, who lost a grandmother and an aunt in Poland in the 1940s. So, I was very moved to hear reports of a rescue operation last week to seek, in a modest way, to take action against the barbaric treatment of Christian sects in the IS heartland of Mesopotamia, the cradle of civilisation. This appears to be an operation by the Barnabas Fund, an international relief agency for the persecuted church with the financial co-operation of certain Jewish organisations and philanthropists, to transfer Christian families to safe havens. I understand that this in an ongoing project to evacuate Christians from those lands where they have dwelt for 2,000 years. What these Christian communities are experiencing is not new to the Jewish communities throughout the Middle East and North Africa, whose persecution led to an exodus of some 850,000 Jews from Arab lands.

The clash of faiths causes these confrontations. It may seem a paradox but the country in the Middle East that is most welcoming to Christians, as the noble and right reverend Lord, Lord Carey, mentioned in passing, is Israel. Christianity is one of the recognized religions in Israel and is practised by more than 161,000 Israeli citizens—about 2.1% of the population. In Israel, there are approximately 300 Christians who have chosen to convert from Islam. Very sadly, such apostasy is not allowed in much of the rest of the Middle East. The noble Lord, Lord Alton, gave a graphic description of many of the injustices that take place and which I cover with the word “apostasy”. I will not repeat them as he did it so well.

Adversity, however, does reveal heroes. A few days ago, one of the heroes of the Holocaust died at the age of 106. I refer of course to Sir Nicolas Winton, who organised eight trains to take 669 children to London from Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia. The British people made room for these refugees and I can only hope that in Britain and the rest of Europe we will rise to the challenge in the present times. We are so fortunate in the United Kingdom but the tolerance we have requires vigilance to ensure that it stays that way. When we see the intolerance of people’s religion and beliefs in many parts of the world, which has been referred to by other noble Lords, we must praise the courage and resilience of those affected; many would have given way to despair.

In the modern world, many now describe themselves as secular. But a very large number of people, as has been mentioned by other noble Lords, follow one of the three Abrahamic faiths: Christianity, Judaism and Islam. Although all three of these faiths share a common history and traditions, they too often emphasise their differences rather than their common beliefs. Christianity has, I believe, 2 billion adherents, Islam 1.3 billion, and Judaism, which comes slightly further behind, a mere 14 million. But there are splits within all these religions, be they Catholic-Orthodox, Catholic-Protestant, Shia- Sunni, or Orthodox-Reform. Whatever the differences, as the Motion before us says, we should as a nation uphold freedom of religion and belief and not enforce or impose our beliefs on others by the sword. The right reverend Prelate the Bishop of Leicester, whom I must compliment on his superb speech, talked about defending religious freedom. That is what this is about. But it is also about allowing one to give up

one’s faith, to change one’s faith, or to have no faith; it is a defence of freedom, of which religion is a part. I will end with the words of Nelson Mandela:

“As I walked out the door toward the gate that would lead to my freedom, I knew if I didn’t leave my bitterness and hatred behind, I’d still be in prison”.

5.28 pm

Baroness O’Loan (CB): My Lords, I, too, thank the noble Lord, Lord Alton, for enabling this important debate. Freedom of religion or belief is not only a fundamental human right in itself: as Pope John Paul II said, it is a,

“litmus test for the respect of all other human rights”.

Wherever Article 18 is compromised, other violations almost inevitably follow.

I endorse the words of the noble and learned Lord, Lord Mackay, in relation to the UK’s modelling of support for freedom of religion and conscience and particularly, as a Catholic, his words in relation to the Catholic adoption agencies. Freedom of religion and conscience is very important in this country still. We have Christian medical practitioners who face massive challenges of conscience simply in doing their jobs. They may even have to leave their jobs in order to comply with their conscience. We need as a country to think again about how we enable and reflect support for freedom of religion and conscience.

As we have heard today, millions in the world are deprived of this most basic freedom and face torture, imprisonment, harassment and even death because of their beliefs. But we can make a difference. Despite the current controversy about the outworking of the European Convention on Human Rights, the UK has a proud history of protecting human rights across the world. We have worked closely with the churches—often the last remaining network of communication in conflicted societies.

In recent years the UK has led the world in historic initiatives to tackle some of the most challenging issues, including modern slavery and sexual violence in warfare. With the same level of commitment, cross-party support and co-operation with our partners in the international community, there is an opportunity to make the principles of Article 18 a reality for so many more people. The UN has stated that,

“no manifestation of religion or belief may amount to propaganda for war or advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence”.

It is extremely encouraging that the Government have made a manifesto commitment to stand up for freedom of religion and I look forward to hearing more detail from the Minister about how this will be put into practice. In particular, will promoting freedom of religion or belief be included as a specific priority in the FCO business plan? Will extra resources be provided to assist our diplomatic missions, particularly those covering the most difficult parts of the world, in achieving this?

Some of the most appalling abuses are taking place in Iraq and Syria, where ISIL continues to slaughter and enslave adherents of minority religions. I will touch briefly upon Iraq’s Kurdish region, where almost 2 million people have found sanctuary so far. It is a

testament to the Kurdish Regional Government that although their population has already grown by a staggering 28% as a result of the refugee influx, they continue to keep their doors open and provide security for people fleeing Mosul or the Nineveh Plains. Many of these refugees are Christians or Yazidis who have seen their family members killed, their businesses seized and their places of worship destroyed. Alongside the local authorities, Christian communities are providing shelter, food, et cetera, to the refugees. The Catholic Church in Irbil alone is accommodating more than 125,000 people, including many Yazidi families. Will the Minister outline what support we are providing to help the Kurdish Regional Government and churches in the region?

Reference has already been made to the thousands of Rohingya Muslims who are making treacherous and often fatal journeys across the Andaman Sea, trying to escape escalating persecution at the hands of Burma’s authorities. Hate speech and xenophobic attacks are allowed to continue unchallenged. The Rohingya have been denied citizenship, cajoled into camps and prevented from accessing humanitarian assistance. The Burmese Government have also passed a package of laws targeting religious minorities which may prevent people converting, marrying or even starting a family. These laws have been condemned by Burma’s first Catholic cardinal, Charles Bo. In a response to me in this Chamber recently, the Minister agreed with that condemnation. Will she update us on the UK’s response to the Burmese package of laws? I would also be grateful for an outline of any recent discussions with other states about the rescue and accommodation of Rohingya refugees.

In Iran, under the principle of the absolute rule of the clergy—velayat-e faqih—during this Ramadan at least 900 people were arrested and many were flogged for not fasting. There is no freedom not to be religious. Many of the sentences against the youth were carried out in public. I would be most grateful if the Minister could confirm the representations that have been made in respect of this. I am encouraged by the Government’s commitment and welcome the opportunity to discuss how the UK will play its part.

5.33 pm

Lord Sheikh (Con): My Lords, I speak today as a Muslim. I also speak as somebody who cherishes the role that all faiths and communities play. I undertake a lot of work with other religious groups. I am a patron of several Muslim and non-Muslim organisations that promote religious harmony.

Our respective religions teach us valuable lessons in morality, help us interpret the world around us and give us guidance when we are in need. For many people, their religion is very precious to them. I agree wholeheartedly with the Motion: a greater priority should be given by the United Kingdom and the international community to upholding freedom of religion and belief.

It is right that everybody in the world should be entitled to this freedom. However, it is being violated by some misguided people. This debate is very topical because of events taking place across the Middle East

and north Africa. My glorious religion of Islam is being hijacked by a tiny minority who have misrepresented it and wholly, totally wrongly portrayed the true message of Islam. I emphasise that Islam is indeed a religion of peace.

What is happening in these countries is strongly against the principles of Islam. What Daesh is doing and saying in Syria, Iraq and other places is totally wrong and un-Islamic. I remind them that it is written in the Holy Koran that there should be no compulsion in religion and that no one should be forced to become a Muslim. The Holy Koran celebrates different beliefs as a means of connecting with people. It is written in the Holy Koran:

“O mankind, indeed We have created you from male and female and made you peoples and tribes that you may know one another”.

My religion teaches us to know and be friendly to people of other faiths. Islam is one of the Abrahamic religions and, according to Islam, the People of the Book are the Jews and Christians. The books of Allah are the Holy Koran, the Torah, the Gospel of Jesus and the Psalms of David. There has been a case in London where a Somali Muslim mosque was damaged and the Jewish community allowed them to pray in the synagogue. We appreciate this very much.

Two of the most successful emperors of India were Akbar the Great, who was a Muslim, and Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who was a Sikh. They both allowed all religious groups to live in harmony in their empires. I hold great personal admiration for Maharaja Ranjit Singh. I have written a book about him that will be published shortly. There are more similarities than differences between people, and we should highlight the similarities in order to establish closer links between communities. It should also be noted that allowing freedom of religion often brings stability and prosperity to a country. As a businessman, I have found it to be beneficial for economic and social development, as well as for the religious communities themselves.

We must use this debate to commend and celebrate what is happening in the United Kingdom. Although the Church of England is the official church, people of all religions are allowed to practise their respective faiths. We are a tolerant and respectful people. This country should be viewed as a model for others to follow. We cannot overstate the importance attached to upholding Article 18, yet so many abuses and violations of it continue to take place. We must lead the world in ensuring that people feel free to practise their religion, both in private and in public. May God help us to achieve this.

5.38 pm

Lord Sacks (CB): My Lords, I, too, thank the noble Lord, Lord Alton, for enabling us again to address this vital issue of religious freedom, and I salute the noble Baroness, Lady Berridge, for chairing the APPG on International Religious Freedom or Belief. I salute the courage of both of them in confronting perhaps the single greatest humanitarian issue of our time. I add my thanks to the right reverend Prelate the Bishop of Leicester for his warm, wise and inspiring contributions to public life, and wish him blessings in the years ahead.

Three things have happened to change the religious landscape of the world. First, the secular nationalist regimes that appeared in many parts of the world in the 20th century have given rise to powerful religious counter-revolutions. Secondly, these counter-revolutions are led by religion in its most extreme, adversarial and anti-Western form. Thirdly, the revolution in information technology has allowed these groups to form, organise and communicate to actual and potential followers throughout the world with astonishing speed. The internet is to radical political religions what printing was to Martin Luther. It allows them to circumvent and outflank all existing structures of power. The result has been the politicisation of religion and the religionising of politics, which, throughout history, has been a deadly combination. In the long run, it will threaten us all, because in a global age no country or culture is an island.

We must do, minimally, three things. First, given that religious freedom is enshrined as Article 18 in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, there should be, under the auspices of the United Nations, a global gathering of religious leaders and thinkers to formulate an agreed set of principles that are sustainable theologically within their respective faiths and on which member nations can be called to account. Otherwise, Article 18 will continue to be a utopian ideal.

Secondly, we must do the theological work. That is fundamental. After the wars of religion of the 16th and 17th centuries, a group of thinkers, among them John Milton, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and Benedict Spinoza, sat down, reread the Bible and formulated some of the most important ideas ever formulated about state and society: the social contract, the moral limits of power, the liberty of conscience, the doctrine of toleration and the very concept of human rights. These were religious ideals based on the Bible, which is what John F Kennedy meant when he said in his inaugural address that,

“the same revolutionary beliefs for which our forebears fought are still at issue around the globe—the belief that the rights of man come not from the generosity of the state but from the hand of God”.

We have not yet done the theological work for a global society in the information age, and not all religions in the world are yet fully part of that conversation. But if we neglect the theology, all else will fail.

Thirdly, we must stand together—the people of all faiths and of none—for we are all at risk. Christians are being persecuted throughout the Middle East and elsewhere. Jews are facing a new and resurgent anti-Semitism. Muslims who stand on the wrong side of the Sunni-Shia divide are being killed in great numbers. Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Baha’i and others face persecution in some parts of the world. There must be some set of principles that we can appeal to, and be held accountable to, if our common humanity is to survive our religious differences. Religious freedom is about our common humanity, and we must fight for it if we are not to lose it. This, I believe, is the issue of our time.

5.43 pm

Lord Harrison (Lab): My Lords, I speak in today’s debate as a loyal member of God’s Opposition. I am particularly grateful to the noble Lord, Lord Alton, and the noble Baroness, Lady Berridge, for highlighting both the freedom of religion and the freedom of belief in the titles of this Article 18 debate and of the all-party group over which the noble Baroness so impressively presides. I also thank Christian Solidarity Worldwide, not only for providing me with excellent material concerning the persecution of atheists and secularists in Egypt and Indonesia but for its pastoral prison visit to Alex Aan, jailed in Jakarta as an atheist.

We atheists must show solidarity with our religious colleagues over religious persecution, especially at a time when atheists and secularists are increasingly joining the growing list of people persecuted worldwide for the beliefs they uphold, whether religious or otherwise. The horror of machete-wielding Islamists slaying humanist bloggers in Bangladesh recently was admirably highlighted by the brave Bonya Ahmed in her recent address to the British Humanist Association at the annual Voltaire lecture.

In the United Kingdom, many will be heartened by the most reverend Primate the Archbishop of Canterbury’s recent observation that religious freedom demands space to be challenged and defended, without responding destructively. This echoed Rowan Williams’s reservation in 2013 that sometimes UK and US Christians exaggerate mild discomfort over social issues such as pro-gay legislation while failing to emphasise systematic brutality and often murderous hostility practised by religious fanatics abroad.

I asked the Minister why humanists and atheists in Britain are still thoughtlessly excluded from contributing to Radio 4’s “Thought for the Day”. Why does the DCMS stolidly exclude the Defence Humanists, formerly the UK Armed Forces Humanist Association, from the annual Cenotaph commemoration? Do dead non-believers, fallen in war defending our cherished values, not deserve a silent vigil in the public square? And why are we conducting this debate in the House of Lords, which still reserves a privileged place for the state religion?

I encourage colleagues not to take the opportunity of the occasional ad hominem criticism of distinguished atheists such as Richard Dawkins. I ask the Minister to reply to the point made by the noble Lord, Lord Alton, about the FCO and whether we are promoting business and trade, which I thoroughly encourage. However, we should use some of our resources to ensure that we promote Article 18 in all its aspects. Can she also update us on what is happening with the blasphemy laws in Malta, and in Iceland, although it is not part of the European Union?

Finally, will Her Majesty’s Government ensure that the hopes and aspirations of non-believers like me are not suppressed by careless oversight when we take our rightful place in the public square?

5.48 pm

Lord Maginnis of Drumglass (Ind UU): My Lords, I am particularly grateful to my noble friend Lord Alton for his tenacity in pursuing this issue. No one whom I have known during my 32 years in Parliament has

been so consistent in his adherence to and struggle for the proper implementation of Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

I intend to use the very short time available to me to consider whether we in the United Kingdom lead by example in respect of our own practice of Article 18 or whether we are a society where leadership is generally content to pay mere lip service. Often it appears to me that we are regularly subjected to the excitement of individualistic excesses that elevate individual selfishness above and beyond the traditional and tried practices and discipline with which I grew up.

Of course society evolves, but why does that mean that some, like the Reverend Richard Page JP, a faithful, public-spirited magistrate in Kent for 15 years and a long-respected member of the Family Court, should be officially and publicly pilloried because, as a practising Christian, he expressed to colleagues, in private, how he was able to reconcile his public duties with his Christian faith? Is there any justice in the fact that the Lord Chancellor in the previous coalition Government should seek to justify having suspended Richard Page by having imposed remedial training in a manner that is little different from the brain-washing and conditioning so beloved of totalitarian states?

Do not tell me that the environment is different. It is not about the difference between chairs and chains; it is about the impact on society. Richard Page’s persecution by Lord Chancellor Grayling began on 2 July 2014 and continues into the second year. In the interim, he is denied even the right to express his opinion to the press. So what was Richard Page’s offence that has nullified the last days of an exemplary working life? He had stated that his lawful and considered judgment that it is better for children to be adopted by both a father and a mother derived from his faith. When a same-sex male couple from Belfast sought precedence over a normal foster couple, he made a decision. Well done Richard Page—and I say that as a father and grandfather.

Where will this case lead? Back in 2010, ex-Lord Chancellor Grayling had been on the other side of the fence when he had supported the rights of owners of bed and breakfast establishments to refuse accommodation to gay couples. Perhaps I should quote the ex-Lord Chancellor at that time, but I shall not. I shall simply ask: what could possibly have induced him to change? Is the future of children less relevant than who may soil the bed linen? Where does this presumptuous and intellectually questionable logic take us in respect of the sixth and eighth commandments? Sorry, I must not mention such things as the sixth and eighth commandments. It is a good job I cannot be suspended—although some may seek to explore the possibility.

I was, of course, alluding to how we must implement our laws on theft and murder. If some intellectual snob decides to undermine them, I take it that the rest of us may be denied any right to mention our Christian or social heritage. I just do not have time to elaborate on other current matters of conscience, such as where Christian bakers are now, apparently, bound by law to promote and advocate matters that offend

their Christian faith. Is that what equality is? Of course, I am protected here—unlike those street preachers in our society who the police are so easily persuaded have given offence.

I hope that the Minister will be able to reassure us about the implementation and continuation of Article 18 within our society.

5.53 pm

Lord Scott of Foscote (CB): My Lords, I am very grateful, as are noble Lords who have expressed their feelings to me, to the noble Lord, Lord Alton, for arranging this debate. I have heard nothing in the course of it with which I have found any possible point of disagreement. I do not want to repeat everything everybody else has said far more lucidly and fluently than I can. I just want to add a few family details that give me a perspective that may be a little different.

Both of my grandfathers were Church of England clergyman. I was brought up as an Anglican and I was sent, as was my sister, to an Anglican school. This was in South Africa. We both came over to England, where all my relations were Anglicans. Accordingly, when in Chicago in 1959 I met, fell in love with and married a Panamanian Latin American Catholic, I wondered what her reception by the rest of the family would be. It was absolutely perfect. They loved her and had the same feelings towards her as I had become accustomed to them having towards me.

The reason I mention this is that that was in a way a mixed marriage, because Anglicans marrying Catholics was not that usual in South Africa. I do not know if it was usual in England, as I was not in England then. The two of us were blessed with four children—two boys and two girls—each of whom was christened and brought up as a Catholic. When I married my wife, I had to sign a chit to say that I agreed to all my children being brought up as Catholics. I was perfectly happy with that. The four children we had are themselves all married and had children, so I have 12 grandchildren.

Two of my children converted and became Muslims. Of my 12 grandchildren, seven of them are Muslims—I was going to say “little Muslims”, but they are not so little, because the oldest is 21 or 22. Of the 12 grandchildren, seven are Muslims, three are Catholic and two are not really anything. Their relationship with one another is as close—as familial—as it could possibly be. They all know that there are differences between them and that they are of different religions, and it does not matter a jot. I can see no conceivable reason why it should. The ones who have no religion at all are always quite curious about what the others believe. The ones who have a religion, have two different religions—Christianity and Islam—which are both monotheistic religions. I do not know whether this is how they would put it, but as far as I am concerned, if there is a God, which I certainly hope there is, they are all worshipping the same God, albeit in slightly different ways.

I simply cannot believe that the divine being—assuming there is one—really minds a jot in what manner the worship takes place, provided that it is sincere and truly meant. Accordingly, having Muslims and Christians

in one family has been no problem at all. They stay with one another; they stay with their aunts and uncles of different religions; the Muslims come and stay with their Christian aunts and uncles and vice versa.

I have been saddened by listening to the remarks made by a number of your Lordships. I am sure that they all relate accurately the horrors and sadnesses that have happened, but nothing of my own experience of a family with mixed Muslims and Christians bears any resemblance to that. Nor do I see any reason why it should with anyone else. As I have said, the fact that there are different religions should not matter, and I believe does not matter. That is the only addition I wanted to make to what has already been said, with which I fully agree.

5.58 pm