The Commonwealth Today: At Talk Given at Liverpool John Moores University – February 12th 2015.

David Alton (Lord Alton of Liverpool)

The main thrust of my remarks this evening will centre on the opportunities which the Commonwealth offers to the City of Liverpool and especially to its universities; and why we should designate Liverpool as “A Commonwealth City.”

As the Romans divided Gaul into three provinces, I will divide my remarks into three parts:

- What the Commonwealth stands for in the modern world;

- What the declaration of Liverpool as a Commonwealth City might offer us; and

- What is the special role of the Commonwealth in promoting education?

By way of preamble, not long after I went to Westminster, some 36 years ago, I joined the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association and have been a member ever since. Worldwide it has 16,000 members.

I was subsequently invited to become Chairman of the Council for Education in the Commonwealth, and for some years I served in that capacity.

I have travelled in many Commonwealth countries and, among speakers for the Roscoe Lecture series, which I host and moderate for Liverpool John Moores University, have been the former Secretary General of the Commonwealth, Sir Don McKinnon, who says “The Commonwealth is a pretty good investment for Britain but it has not always used it best.”

In that Roscoe Lecture Sir Donald saw the Commonwealth, and so do I, as a unique organisation which seeks to entrench a genuine culture of democracy and interdependence in a fragmented and increasingly dangerous and intolerant world.

So I’m a fan – but is this about more than motherhood and apple pie?

Turning to those three provinces of Gaul:

- What the Commonwealth stands for in the modern world

Let’s be clear about what the Commonwealth is and what it isn’t.

It isn’t a voting bloc of nations – like “the Communist bloc” of yore – a geographical bloc like the African Union – a militarised bloc – like NATO or the Warsaw Pact – a trading organisation like ASEAN – or a legislative body like the European Union. Nor is it a mini United Nations.

Perhaps the nearest parallel is with the Council of Europe, Europe’s oldest intergovernmental organisation, covering some 820 million citizens and is an advisory international organisation promoting co-operation between European countries and working to uphold human rights.

Inevitably, the Commonwealth’s identity is shaped by shared history, friendship, and an increasing understanding that blocs have their limitations – and produce their own strait-jackets – whereas looser networks can often produce innovative and more interesting relationships and opportunities.

As we commemorate the First and Second World Wars we should never forget the willingness of Commonwealth combatants to give their lives in defence of our freedom. In the Great War there were 1.5 million Indian volunteers alone.

If, to try and avoid such conflicts, you believe in “soft power” – and I do – or smart power as I prefer to call it – then you will surely conclude that the Commonwealth, the British Council and the BBC World Service, are three of the best ways of delivering it.

And if you believe in “development power” – as the best antidote to the illiterate barbarism and determined uniformity of groups like Daa’sh – ISIL – or Boko Haram and the rest – then it must be right to focus our now ring-fenced 0.7% commitment of overseas aid (90% of which is development aid) than through the Commonwealth – where 800 million live in official poverty? In 2014 we allocated around £2 billion for development projects in Commonwealth countries.

The virtue and point of a global organisation, in a world where communications and travel have never been easier but also where we face global challenges – from climate and environmental degradation to grinding poverty and health pandemics – is self-evident. Although, as Sir Donald McKinnon reminded us, we have not always used it for the best.

Today, some 53 independent and sovereign states comprise this voluntary organisation par excellence. Some 2.2 billion people live in the Commonwealth, 60% are under the age of 30.

The Commonwealth spans five regions and is diverse in a world where Jihadists and totalitarian regimes seek to impose a brutal uniformity. It has a combined GDP of £5.2 trillion.

It is not a rich man’s club and includes some of the poorest as well as richest nations; some of the fastest growing economies; some of the most populous; and some – its island states – of the most sparse and remote. From micro-states in Polynesia to members of the G8, the Commonwealth straddles north and south, east and west, linking nations and people throughout the world.

The Commonwealth also unites nations which hold divergent religious and secular beliefs – and in a world riven by communal hatred, suspicion, fear and intolerance, what a wonderful house it is that can provide a home for the dignity of difference.

Today’s rising generations place so much emphasis on social networking and interconnectedness. With its 80 intergovernmental civil society, cultural and professional organisations, the Commonwealth knows a thing or two about networking and interconnectedness.

Comprising over a third of the world’s population, the Commonwealth has a fascinating past, but is not a museum, it is a model which could offer the world a more hopeful future.

But just what hope does it hold out for us; for what does the Commonwealth stand?

Look at its Charter.

In a year that we celebrate landmark historic anniversaries – the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta, the 750th anniversary of the barons meeting at the first Parliament in Westminster, and the fiftieth anniversary of the State Funeral of Winston Churchill – it is worth recalling that it is only two years since this 66 year old forward looking organisation set out its core values in its formal Charter.

In a single and highly accessible document the Charter draws together the values and aspirations which unite the Commonwealth – democracy, human rights and the rule of law.

It is said that President Nasser of Egypt once said to Prime Minister Nehru of India “I put my extremists in prison. What do you do with yours?” Nehru replied “I put mine in Parliament”. His were the values of the Commonwealth.

The Charter commits its members to upholding democracy; human rights; peace and security; tolerance, respect and understanding; freedom of expression; separation of powers; rule of law; good governance; sustainable development; environmental protection; access to health, education, food and shelter; gender equality; and the importance of young people and civil society.

Clearly, not all Commonwealth countries have turned the rhetoric into a reality but by agreeing them it enables levels of mutual accountability which are not based on imperialism but on shared aspirations.

At a practical level, having officially observed over seventy elections, and having been willing to suspend membership – in the case of countries like Zimbabwe or Fiji – and see the withdrawal of countries like Pakistan and South Africa – for reasons ranging from military coups to racism – the Commonwealth has made clear what it stands for.

It is significant that many of those countries, subsequently sought readmission – and even formerly Francophone countries like Rwanda, with no historic link to the UK, have become members. Clearly, those countries see the Commonwealth as a strong and respected voice in the world, speaking out on major issues; and proactively strengthening and enlarging its networks. It also says a great deal about this country’s most important export: its language.

The Charter affirms that a special strength of the Commonwealth lies in its combination of diversity and shared inheritance in language, culture and the rule of law; being bound together by shared history and tradition; by a respect for all states and peoples; by shared values and principles and by concern for the vulnerable,

In a nutshell, the case for the Commonwealth is grounded in its ability to be a compelling and effective force for good – a good deed in a pretty nasty world – and to be a non-threatening place and network where we can promote development and progress.

So what relevance does any of this have for the city of Liverpool?

- What might the declaration of Liverpool as a Commonwealth City might offer us?

I was delighted to hear that Edward Harcourt, Pro-Vice Chancellor of Liverpool John Moores University, who invited me to give this lecture, and Cllr. Richard Kemp of Liverpool city Council – had been talking about how Liverpool could take a more active role in promoting commonwealth links.

I first met Richard 43 years ago when he asked me to speak at a political meeting for other young people in a room over a pub in Leyland. I made no apology then, and do not do so this evening, for saying I love my country but believe we, as a maritime nation, are called to have an internationalist vision and to join forced with like-minded nations in upholding shared values.

It is why, as a boy I joined the Anti-Apartheid movement, why I argued for membership of the Common Market, why I helped found charities like Jubilee Campaign, and why I chair parliamentary committees like the All Party Group on North Korea.

The United Kingdom is at its best when it is outward looking and at its worst when it becomes narrow or xenophobic: the same is equally true of what once called the Second City of the Empire, the Gateway to America and arguably the world’s first global city – the City of Liverpool.

Liverpool has grown into a global city because of the people who have settled here or passed through it – and rightly describes itself as the whole world in one city. Equally it is the whole Commonwealth in one city.

Liverpool’s historic role and status as a maritime centre and port city has contributed to its diverse population – drawn from a wide range of peoples, nations, cultures, and faiths. Home to the oldest Black African community in the UK it is home, too, to Europe’s oldest Chinese community.

Granted its Borough Charter in 1207, in the ninth year of the reign of King John, Liverpool formally became a city in 1880 – although the urbanisation of the late 18th century had already transformed it – with expansion driven on through the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. By the beginning of the 19th century 40% of the world’s trade passed through Liverpool’s docks and at times its wealth exceed even that of London.

Any visitor to the city’s Maritime Museum quickly realises that two dark shadows hang over the history of Liverpool – the slave trade and the Irish famine.

In 1847 Dr.Duncan, the city’s pioneering Public Health Officer recorded over a thousand fatalities among Irish people fleeing the famine and there were an estimated 20,000 street children with 100,000 people living in abject poverty. In 1868 48,000 children between the ages of 5 and 14 attended no school.

Our link with a tragedy that cost Ireland 1 million lives is written in the city’s DNA but in Africa Liverpool is remembered as the engine room of the slave trade.

In 1807 the year in which William Wilberforce succeeded in abolishing the trans-Atlantic trade, there were four million people in slavery worldwide. He was assisted by the Liverpool slave trader, John Newton – later of Amazing Grace fame – who published his influential pamphlet “Thoughts on the African Slave Trade” and gave evidence in Parliament about the horrors and cruelties in which he had been involved. With Newton stands the remarkable William Roscoe.

Notably, during his three months as a Member of the House of Commons, Liverpool’s William Roscoe, one of the founders of the college which evolved into this University, voted against the slave trade and spent the rest of his life championing the oppressed, promoting education, and developing the city’s culture and civic institutions. In Parliament, Roscoe said “I consider it the greatest happiness of my existence to lift up my voice on this occasion with the friends of justice and humanity.” In his epic poem, “The Wrongs of Africa” he warned his countrymen: “Forget not Britain, higher still than thee, sits the great judge of nations, who can weigh the wrong and can repay.”

Almost 200 years later, at the turn of this Millennium, I took a Declaration from Liverpool to West Africa – expressing the city’s “sense of remorse” over the effects of the slave trade “on countless millions of people” and the City Council’s unanimous decision to “co-ordinate the use of all its powers to foster better race relations, greater equality of opportunities and even greater diversity.”

.

So, it’s important to know your history but not to become trapped in or to become prisoners of your own history. The Chinese calligraphy for crisis can also be read as opportunity. Perhaps that’s the spirit in which we need to view our history and the opportunity which the Commonwealth offers us.

As a British-Irish city it would be wonderful if we could play some part in encouraging Ireland to re-join the Commonwealth. It was excluded in 1949 when it became a Republic, although one year later the rules were changed to enable India to remain a member.

10% of British people have a grandparent or parent of Irish descent – as I do myself. I have British and Irish passports, as my children do. And our links are not only through blood. Britain’s biggest export destination in the European Union is Ireland.

But our relationships have been disfigured by centuries of violence. Last year saw a further healing of our shared history when President Michael D. Higgins returned the State Visit of Her Majesty the Queen and she entertained Martin McGuinness at Windsor Castle.

It is, of course, entirely a matter for the Irish Government but people need to put out a welcome mat and what a message it would send to divided societies the world over.

But if Liverpool saw itself as a Commonwealth City it could do much more than that.

In 2002 the Manchester Commonwealth Games generated more than £2 billion; last year’s Glasgow Games drew in more than 6,500 athletes and officials in 17 sports and a global audience of around 1.5 billion people. With its reputation for sporting excellence Liverpool can learn from those experiences; but its reputation goes much wider than this.

Since 2004 much of the city’s waterfront has had World Heritage status and its economy also continues to give it international, world status. The Post-Panamaz container terminal extension will berth some of the world’s biggest container vessels – doubling the Port’s container capacity from 700,000 containers each year to 2 million by 2020. The new cruise liner terminal, situated close to the city centre and Liverpool One and wonderful facilities, such as the Echo Arena, and some fine hotels, once again makes Liverpool a city which can generate visitors, conferences, opportunities. Since its 2008 designation as European Capital of Culture – which through overnight visitors generated £188 million into the local economy – tourism has been estimated to be worth over £1 billion a year to the city.

Yet, what is there in Liverpool that specifically celebrates the Commonwealth or seeks to promote and deepen our links to Commonwealth countries and Commonwealth cities?

Among the exhibits at the Museum of Liverpool is the cotton brokers’ ring which was the first purpose built stand of its kind in England and was made in 1906.

Liverpool’s Cotton Exchange directly tapped into world markets with countries like India. Today, with a quarter of the world’s population, 20% of the world’s trade and thousands of listed companies, and the English language, the Commonwealth offers unsurpassed opportunities to a city like Liverpool – and we should seize the opportunity with enthusiasm.

The cotton brokers’ ring might be an appropriate symbol to promote the ring of friendships, shared experiences, and business opportunities which the Commonwealth could offer Liverpool today. One of the greatest of those opportunities is represented by education.

- What is the special role of the Commonwealth in promoting education?

Liverpool has three fine universities – home to more than 50,000 students – along with its wonderful School of Tropical Medicine, of which I am a Vice President.

Founded in 1881 by William Rathbone, Liverpool University has some 21,000 students pursuing over 450 programmes spanning 54 subject areas; LJMU traces its foundation to 1823, is the biggest of the three (the twentieth largest in the UK), with more than 24,000 students, including 4,270 postgraduate students; while Liverpool Hope, the only ecumenical university in Europe, home to 7,885 students.

The Liverpool School of Tropical medicine, situated in the Ward and the Constituencies which I represented, was established in 1898 and became the first institution in the world dedicated to research and teaching in tropical medicine.

With a research portfolio of £220 million it has established a global reputation – not least thanks to the significant support of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Welcome Trust and DFID.

LSTM has partnerships and projects operating in over 70 countries – many of them Commonwealth countries – and offers a range of postgraduate education programmes, teaching over 600 students from around the world.

In parenthesis I might say that when I travel to some of the countries from which Liverpool and the UK draws international students, one question is always raised:

“Why does the UK insist on a visa system which is so hostile to students entering the UK?”

It’s a question which, in turn, I ask the Government and have yet to receive a satisfactory reply. I am also disappointed by a retrenchment on commonwealth scholarships. It is worth noting that in his youth the Canadian Governor or the Bank of England, was the beneficiary of a Commonwealth Scholarship.

However, for the first time in decades the number of international students has declined – most notably from India. Is it any wonder, then, that despite 250 years of trading with India, Switzerland is now said to have more trade with India than we do. These things feed into one another and this is incredibly short-sighted.

While I served as Chairman of the Council for education in the Commonwealth I was equally critical of the decision to reduce funding for students from the poorest Commonwealth countries.

All of this, notwithstanding, whether in its undergraduates or post graduates Liverpool should truly see itself as a City of Learning. It should not lose the reputation of its former colleges – such as, St. Katherine’s, Notre Dame and Christ’s – as some of the best Colleges of Education in Britain for the formation of teachers. Take the example of Malaysia.

In 1953, despite a sometimes tortured relationship with the UK, Malaysia joined and remains a member of the Commonwealth.

In those days many Malaysian teachers were trained here at Kirkby Teacher Training College, which closed in 1962.

Today the traditions of the college are incorporated in Liverpool John Moores. The university also has a significant presence, a regional office and graduations in Kuala Lumpur and a thriving cohort among its overseas students, studying in Liverpool. Many of those trained here have run Malaysia’s schools and colleges – cherishing the values they embraced.

Take two other Commonwealth countries: Nigeria and Pakistan.

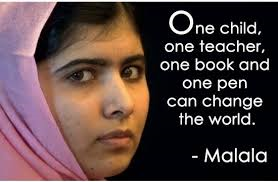

In Nigeria Boko Haram – which means eradicate western education – routinely murders students and abducts girls and young women to prevent them receiving an education. In Pakistan the Taliban shoot girls like Malala Yousafzai for seeking an education.

They and Boko Haram fear what Malala stands for and summed up in her phrase: “One child, one teacher, one book, one pen can change the world.”

Elsewhere, especially in Africa – home to so many Commonwealth countries – the streets are awash with orphans – some of the 150 million in the world. Uganda has nearly 3 million – with 1 million orphaned by AIDS.

The AIDS pandemic, conflict – represented at its most graphic at the genocide sites I have visited in Rwanda – urban drift to the shanti towns I have seen first-hand in places, like Kibera, where people live in utter squalor and earn an average of less than $1 a day, human trafficking and corruption, all provide fertile breeding grounds for Jihadists and violent organisations.

The antidote to this will always be education. As the son of an immigrant whose first language wasn’t English, born into a home without inside sanitation, and who had no-one on either side of the family who had ever entered higher education, I know this to be emphatically true. But don’t take it from me.

Nelson Mandela, incarcerated for 27 years, would become an inspirational Commonwealth leader, the embodiment of reconciliation, forgiveness and true nobility. He said of the Commonwealth, which played such an important role in the ending of apartheid:

‘The Commonwealth makes the world safe for diversity’.

As an orphan himself he insisted:

“There can be no keener revelation of a society’s soul than the way in which it treats its children…We owe our children, the most vulnerable citizens in our society, a life free of violence and fear.”

And he also said “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world”

Is this not a challenge which we might embrace?

On a visit to Kenya, to open a school house for blind children, I was struck by the slogan which the children had chosen to hang over the door: “Give us only opportunity, not sympathy.”

On another occasion, in another part of Kenya, in the remote region of Turkana, I saw ways in which new educational opportunities are opening up. In a large hut in the centre of a compound, solar energy was helping to power internet links and several students were gathered around screens soaking up an education.

The Commonwealth has recognised this through the Commonwealth of Learning – an intergovernmental organisation created by Commonwealth Heads of Government to encourage the development and sharing of open learning/distance education knowledge, resources and technologies. Headquartered in Canada it is an exciting initiative helping developing nations improve access to quality education and training.

Its strategic goals are quality education for all Commonwealth citizens; human resource development in the Commonwealth; and the harnessing technology to achieve development goals.

COL has been the catalyst for initiative and projects such as the Open University of Tanzania; a medical education network in Malaysia; and a media centre for Asia based in New Delhi. Its focus has included open schooling, teacher education, a virtual university for small states; technical and vocational skills; life-long learning for farmers; and opportunities for women and resource poor communities.

Is this not one of many opportunities for our Liverpool universities and our educationalists: for our city? I wonder how many of our city’s schools are linked to the Commonwealth class project, in which the British Council and BBC have played a leading role, and which is promoting Commonwealth identity to seven to 14 year olds by linking no fewer than 100,000 Commonwealth schools on line?

Designating the city as a Commonwealth City and backing it up with political and civic commitment, in partnership with key institutions, entrepreneurs and commerce, with some achievable practical objectives and projects, would be good for Liverpool and good for those with whom we engage. We could make a start by flying the Commonwealth flag from the Town Hall and public buildings on Commonwealth Day – celebrated on the second Monday of March.

At the outset, I said that like the Romans, I would divide my version of Gaul into three parts:

What the Commonwealth stands for in the modern world;

What the declaration of Liverpool as a Commonwealth City might offer us; and

What is the special role of the Commonwealth in promoting education?

I don’t know that I have done justice to these themes but I know that I am not among those who dismiss the Commonwealth of little importance – a relic which fosters delusions of British influence on the world’s stage. Quite the reverse.

This country and the Commonwealth can be a compelling and dynamic force for good in the world – and in among the surge in demands for human rights, for law based societies, for democracy, and as we face changing economic circumstances, global uncertainty, new threats to peace, stability, diversity and the environment, and changing patterns of trade and economics, I know that we need more networks and organisations like the Commonwealth – not fewer.

Ends.

David Alton –Lord Alton of Liverpool – is Professor of Citizenship at Liverpool John Moores University and Director of the university’s Roscoe Foundation for Citizenship.

University Details: Roscoe Foundation for Citizenship, Liverpool John Moores University, 0151 231 3852.

To listen to a Roscoe Lecture: visit http://www.ljmu.ac.uk/roscoe/