The Bilateral Agreement for the Promotion and Protection of Investments between the United Kingdom and Colombia

Scroll Down For The Full Debate…

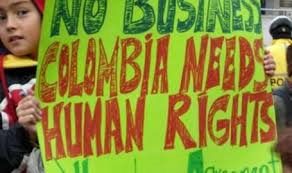

Mgr Héctor Fabio Henao, director of CAFOD’s Colombia partner SNPS, came to the UK with two Colombian community leaders. Mélida Guevara and Jesús Alberto Castilla, whose communities have been torn apart by 50 years of internal conflict, visited the UK to tell the government and CAFOD supporters what they can do to help.

The Bilateral Agreement for the Promotion and Protection of Investments between the United Kingdom and Colombia

Lord Alton of Liverpool (CB):

My Lords, it is a great pleasure to follow the noble Baroness, Lady Hooper, whose knowledge of Latin America is probably unparalleled in your Lordships’ House. She and I are both members of the All-Party Parliamentary Friends of CAFOD, for which I serve as treasurer. A few months ago, with the Labour Member of Parliament, the right honourable Tom Clarke, who chairs that group, I met a group of Colombian human rights advocates, indigenous Colombians and Afro-Colombians, who were in the UK as guests of that charity. CAFOD is also part of the coalition ABColombia, which is an alliance of CAFOD, Christian Aid, Oxfam, SCIAF and Trocaire. I was profoundly moved by the commitment of those who have put their own lives at risk in working for peace and human rights in Colombia, but also shocked by the scale and nature of some of the egregious violations of human rights which they described. I promised them that, if the opportunity arose, I would try to draw Parliament’s attention to the dangers that they faced. Therefore, I am particularly grateful to the noble Lord, Lord Stevenson of Balmacara, for moving this Motion today, which gives us the opportunity to raise questions and to do just that.

12.15 pm

Although there has been some improvement in the political and economic situation in Colombia, guerrillas and successor groups to paramilitaries have continued to be involved in significant acts of violence. Human rights defenders, trade unionists, journalists, indigenous and Afro-Colombian leaders and IDP leaders regularly face death threats, intimidation and other abuses.

Although the Administration of President Juan Manuel Santos have consistently condemned threats and attacks against rights defenders, in a culture of impunity, perpetrators are rarely brought to justice. After decades of internal conflict, with 220,000 people killed, the Government are now in peace talks with the FARC guerrilla group but, with the exception of Syria, Colombia, with a phenomenal 5.7 million displaced people, has the highest number of internally displaced people in the world. As the advocate whom I met explained to me, the displacements have frequently come about as a direct consequence of corporate investment, when land is wanted for agriculture, oil exploration or coal mining.

In 2011, the Colombian Government introduced a welcome law to restore to victims some of the 2.2 million hectares of the 6.8 million forcibly taken from them. To date, according to Colombia’s comptroller general, less than 1% of that land has so far been restored. The continuing conflict has also seen some victims, to whom land has been returned, once again violently displaced. According to the Colombian constitutional court, 34 groups of indigenous peoples are currently at risk of extinction. The court identified forced displacement as the major cause. Colombian indigenous peoples’ land is generally in areas rich in natural resources. To safeguard the people and the land, Colombia will need to legislate to protect them from the huge influx of multinational corporations. As I will argue, instead of protection, the UK has created in this trade treaty something that will benefit British businesses but harm exploited and vulnerable people.

It is not just the people who are at risk—it is also the people who try to protect those at risk. What happens to people who challenge rapacious business interests, international conglomerates or the warlords and guerrillas who have profiteered at the expense of the poor? I would like to give the committee an illustration. In May, Colombia’s Senate enacted an important Bill that is a major step in aiding and protecting sexual violence survivors, especially those who are raped or assaulted by guerrillas, paramilitaries, Colombian forces, or others in the context of the country’s decades-long conflict. Colombia’s new law stipulates that sexual violence can constitute a crime against humanity under the standards provided for in international law. But it is indicative of the country’s lawlessness that Ana Angelica Bello, one of the most vocal advocates of this law, died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound under circumstances that still remain unclear. Angelica, from rural Colombia, was forced off her land by armed groups. She was raped by men she believed to be former paramilitary as punishment for her subsequent advocacy and activism.

Today’s welcome debate, triggered by the noble Lord, Lord Stevenson, should ring alarm bells about human rights in Colombia and particularly alert us, as the noble Baroness, Lady Hooper, said, to the dangers faced especially by women such as Angelica and by lawyers and human rights defenders. Professor Sara Chandler, on behalf of the UK members of the International Caravana of Jurists points out that the bilateral investment treaty with Colombia ratified on 10 July is in danger of worsening the situation of human rights’ defenders. She particularly draws attention to an issue raised by the noble Lord, Lord Stevenson, about how we are going to monitor how this treaty works out in practice in future. The Caravana is comprised of international lawyers and includes judges, solicitors, barristers, academics and law students. At the request of its counterparts in Colombia, it has visited the country since 2008 and has gathered first-hand accounts of lawyers who have faced daily threats of violence, kidnapping and death just for undertaking their professional duties. Since January 2012, it has recorded 37 threats directed towards lawyers or human rights defenders operating as legal representatives, with 18 killings during that period. Incidentally, it will be returning to Colombia next month.

Caravana points out that the United Kingdom has significant leverage, as Britain, as we have heard, is second only to the United States in foreign investment in Colombia and that new investment treaties and fair trade agreements such as the BIT offered the opportunity—sadly, not taken—to include safeguards to ensure that British businesses investing in Colombia will never be complicit in serious human rights violations. It also points to the serious imbalance between the significant protection afforded to investors, compared to the lack of protection and resources available to the indigenous people and local communities affected by development, and states that that disparity places the United Kingdom Government in a position of direct inconsistency with their commitments under the United Kingdom action plan Good Business, which implements the Ruggie UN Guiding Principles on Human Rights.

The action plan contains a commitment that,

“agreements facilitating investment overseas by UK or EU companies incorporate the business responsibility to protect human rights, and do not undermine the host country’s ability to meet its international human rights obligations”.

The bilateral treaty with Colombia remains, ominously, completely silent about those responsibilities. Why is that? This is one of the first tests of whether the sentiment and rhetoric will be matched by the reality. Therefore, it does not bode well. Are we to be simply what John Ruskin once described as a “money-making mob”?

Specifically, in the peace talks in which the Colombian Government are engaged in, they have committed themselves to the land reforms to which the noble Lord, Lord Stevenson, referred. Have the Government discussed what impact the treaty will have on the Colombian Government’s ability to return land and to implement the Havana agreement on land reform? Will the Minister, the noble Lord, Lord Livingston of Parkhead, also confirm that the largest UK investments in Colombia are in mining, with all the land requirements which mining entails? Will he also tell the Committee how much of the land violently seized and confiscated in Colombia’s conflict is in areas rich in natural resources and on land owned by indigenous peoples, Afro-Colombians and peasant farmers who are waiting for their land to be restored—the people I referred to at the outset of my remarks? Will he explain to the Committee how restoration is compatible with pursuing Britain’s mining interests, and which will take precedence—as if we do not already have a hint as to the answer? Will he also say how we will guarantee the rights and obligations to which I referred of indigenous peoples in respect of their free, prior and informed consent, their right to self-determination and to their own development, which are guaranteed in United Nations International Labour Organization Convention 169 and the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples?

Are we simply to be a money-making mob, or will the Government insist that human rights which we expect for ourselves will be applied in situations where our monetary clout gives us influence and leverage? It is really unacceptable that we have created a self-serving agreement which incorporates a disparity in providing considerable—some would say, excessive—protection for British investment while the ability of the Colombian state to regulate that investment is restricted. The investor-state dispute settlement provisions could have been used as an opportunity to incorporate human rights provisions and to enable a third party, such as an NGO, to make representations in the dispute process. As things stand, the UK-Colombia BIT has no such safeguard. We could do a lot worse than emulate the EU-Canada free-trade agreement, CETA, which incorporates safeguards affirming the right of states to regulate in pursuance of legitimate public interest objectives.

In another context, the House of Lords EU Committee has expressed doubts about including an investor-state dispute settlement that gives investors the right to challenge measures adopted—in this case, by the UK—in the public interest. The committee recommended that before including an ISDS clause, a number of safeguards should be in place, including to,

“improve transparency around ISDS proceedings, for example by making hearings and documents public, allowing interested third parties to make submissions”.Those safeguards do not seem to form part of the bilateral investment treaty with Colombia.

To conclude, I therefore ask the Minister: what plans the Government have to incorporate safeguards to the investor-state dispute settlement provisions in the treaty to enable the UK to ensure that its foreign investments do not make us complicit in serious human rights violations? At the very minimum, will the Government consider creating a system of annual monitoring of the treaty in terms of its human rights impacts and impact on the peace agreements, with the results to be incorporated in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office annual human rights report? What plans are there to incorporate safeguards to the investor-state dispute settlement provision, to ensure that the United Kingdom complies with its human rights obligations and commitments made in Good Business on implementing the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights?

Colombia is listed as one of the countries of concern in the annual FCO human rights report. Instead of promoting policy changes to improve human rights, the bilateral agreement could obstruct Colombia’s ability to promote policies that achieve improvements in human rights. Given the record levels of UK investments in Colombia, there was simply no need for this treaty in the first place. Ministers should give further thought to the consequences of its ratification, along with the ethical implications of its promotion.

——————————————————————————————————-

The full debate…

Grand Committee

Wednesday, 30 July 2014.

Arrangement of Business

Announcement

Noon

The Deputy Chairman of Committees (Baroness Stedman-Scott) (Con): Good afternoon. If there is a Division in the House, the Committee will adjourn for 10 minutes.

The Bilateral Agreement for the Promotion and Protection of Investments between the United Kingdom and Colombia

Motion to Take Note

Noon

Moved by Lord Stevenson of Balmacara

That the Grand Committee takes note of the Bilateral Agreement for the Promotion and Protection of Investments between the United Kingdom and Colombia (Cm 8887). 3rd Report from the Secondary Legislation Scrutiny Committee.

Lord Stevenson of Balmacara (Lab): My Lords, the UK-Colombia bilateral investment treaty, or BIT, is designed to provide important protections to British investments in Colombia. My purpose in raising the issue today is to draw attention to the fact that these protections are controversial. Without putting down this Motion there would have been no chance to discuss these issues, which many people inside and outside Parliament would like to see raised. These concerns include a feeling that the balance of the treaty may be wrong, in that it gives excessive protection to investors while limiting the ability of the host country to regulate the FDI, and a question about whether the treaty deals with business and human rights, in the light of the growing impact of the UN’s generally accepted principles on business and human rights.

However, it is important to note at the start of the debate that UK business does not appear to need this agreement to encourage investment in Colombia. Colombia is one of UKTI’s 20 high-growth markets and the UK is already the second largest foreign investor, much of it in the extractives industry. Between 2009 and 2012, UK exports of goods and services to Colombia rose by 126%, the highest level of any of our major markets. Over the next four years, it has been predicted that Colombia will invest £50 billion in oil and gas and, over the next eight years, around £60 billion in infrastructure.

I am extremely grateful to the noble Lord, Lord Livingston, for providing some background information about the treaty, which has been very helpful to me in preparing for this debate. From this I note also that he has been active in working on various other things. I

30 July 2014 : Column GC632

think that we all got these documents this morning and it is very good to see them, following a discussion where we felt that more could be done to try to proselytise for TTIP and other work in this area. I am glad to see that these documents have come round. However, the background information supplied suggests that the BIT was actually negotiated during 2008-09 but that ratification has been delayed as the treaty of Lisbon, which transferred exclusive competence for FDI to the European Union, entered into force before the agreed text was signed.

In view of this, some people have argued that the text of the treaty is out of date and should instead reflect the direction of travel as envisaged in more recent treaty negotiations, such as TTIP. It is also the case that during the time that has elapsed since the treaty was negotiated, the UK has embraced the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and is one of the first countries to produce an action plan, which we certainly welcome. However, we accept that the debate on how future BITs should be structured to ensure a satisfactory balance between protection of investments and the right of local Governments to regulate in the public interest is not new. We also accept that the text of the current treaty departs substantially from previous UK practice, although I suspect that some of the changes made are not necessarily going to be made more acceptable as a result.

It is interesting to note that the BIT was ratified by the current Colombian Government in 2013 and that they have subsequently been pressing the UK Government strongly, at both ministerial and official level, to complete their ratification process at the earliest opportunity. This suggests that the Colombian Government view the entry into force of the BIT as positive, bringing benefits to Colombia through helping attract new foreign investment, and have considered that these benefits outweigh the risks of investor claims and impacts on public policy. But in the unlikely event that anyone thinks that these are hypothetical risks, Colombia’s neighbours Ecuador, Peru and Mexico have been the subject of 14, three and 10 claims respectively. I am told that $81.4 million is the average compensation paid to investors over the 83 known ISDS awards in favour of the investor to July 2013. Indeed, last year’s award of $1.17 billion to Occidental from Ecuador was the equivalent of the country’s entire education budget.

I am sure that the Minister will seek to persuade us, when he comes to respond, that despite the time that has elapsed the Government believe that the signed text reflects the current public debate and is fit for purpose in that context. However, some substantial concerns remain and I hope that the debate will help persuade the Government of the need to reflect carefully on whether the treaty correctly balances providing protection for investors and giving the Colombian Government the space they need to regulate in the wider public interests.

Other noble Lords, I am sure, will raise other points around this topic. I will therefore limit myself to two examples. The first is land reform. The treaty includes a form of investor-state dispute mechanism—narrower, as we are told—which will allow Columbia to be sued

30 July 2014 : Column GC633

in an international arbitration tribunal. These tribunals take place behind closed doors and grant investors the right to sue democratically elected governments. However, neither the host government nor communities affected by such investments have rights to challenge that investment. As the Minister knows, land issues have been at the heart of the Colombian internal conflict, and nearly 6 million people have been forcibly displaced, so many people think land reform is the key to the peace discussions with FARC, which are currently taking place in Havana.

Will the Minister explain why the treaty will not prove challenging to the Colombian Government in pursuing land reform issues? Will he also reassure us that it will not put at risk implementing the land and victims law passed in 2011, under which land is due to be returned to victims of the recent conflict? Will he also comment on the suggestion that the solution to the problems posed by ISDS mechanisms would be to enact proper domestic legislation to protect FTI investors, as is happening in South Africa?

Secondly, on human rights, because of the long period of gestation of this treaty, it was drafted before the emergence of the UN’s Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Rightly, the EU is committed to signing treaties only with countries that meet its values of democracy, the rule of law and respect for human rights. The Colombian Government have made good efforts to strengthen the rule of law, to condemn human rights violations and take action against illegal land appropriation, and there are now significant legislative and public policy initiatives in the field, which we welcome. However, there is more to come and we need to make sure that we support and get behind these initiatives.

Equally, the UK has made significant commitments recently in its action plan to implement the UN’s Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. In particular, the UK has undertaken to ensure that,

“agreements facilitating investment overseas … incorporate the business responsibility to respect human rights, and do not undermine the host country’s ability to meet … its international human rights obligations”.

I do not see that wording in the treaty. When the Minister responds, will he point to where the text reflects that sentiment, and explain how the UK will ensure that this treaty does not undermine Colombia’s ability to meet its international human rights obligations?

Will the Government not go further? Given that the situation on the ground is still developing, and bearing in mind our commitment to the UN guiding principles, does the Minister agree that it might be appropriate if he prepared an annual monitoring of the treaty in terms of its human rights impacts, with the results of this monitoring perhaps incorporated into the FCO annual human rights report?

Finally, when this treaty was considered by the Secondary Legislation Scrutiny Committee, the instrument was drawn to the special attention of the House on the grounds of policy interest. The committee had some reservations about the effectiveness of the protection for the investors because of the way the treaty is worded, and picked up on the difficulties these arrangements may create in relation to the human rights of certain groups within Colombia.

30 July 2014 : Column GC634

The committee’s report goes on:

“We have offered the Government the opportunity to respond and, if received, we will publish the response in our next report”.

I checked the other day and no response had yet been submitted. Will the Minister say whether the Government intend to respond to the Secondary Legislation Scrutiny Committee and if so, when this might be received? I beg to move.

Baroness Hooper (Con): My Lords, as someone with a strong interest in Latin America and as a member of the European Union Select Committee, it is important to question the Government on this bilateral agreement. I congratulate the noble Lord, Lord Stevenson, on having spotted the need and opportunity for this debate, and on setting out the background so clearly.

There are three main areas of concern, which have already been referred to and no doubt will arise in other contributions. First, the treaty excludes important reforms currently being considered at European Union level in relation to the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership between the European Union and the United States, on which the European Union Select Committee has reported. These are designed to mitigate some of the serious problems associated with investor-state dispute settlements.

Secondly, it does not contain human rights obligations on investors in spite of the Government committing to this in our recent national action plan on the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Thirdly, it creates legal uncertainty and could undermine the land reforms referred to by the noble Lord, Lord Stevenson, which are vital to the peace process in Colombia. In that, the treaty is inconsistent with other areas of government policy which seek to support human rights and peace in Colombia.

However, I would go further. Although this is a general point which could affect all trade treaties, it has particular significance for Colombia. If we think that United Kingdom companies operate to high levels and standards in other areas which have not been emphasised, we should seek to replicate those standards and levels in our international trade treaties. For example, corporate social responsibility could and should be encouraged, and referenced to in these agreements. A company’s involvement in social issues in its neighbourhood and community are well appreciated and are now the norm in the United Kingdom. UK companies equally should feel obliged to follow similar standards in their operations overseas.

By the same token, environmental interests and concerns should be taken into account. I am interested to see that the department’s leaflet referring to the EU-US trade treaty refers to the fact that the high environmental standards and targets which we now have in place in this country are non-negotiable. I believe that in order to encourage that there should be a system of green points for those companies which commit to action in this area. For example, a project in Colombia with which I have become involved focuses on the Media Magdalena valley, an area which during the difficult terrorist periods was completely closed.

30 July 2014 : Column GC635

People moved away and, therefore, flora and fauna had a wonderful time getting on without human interference.

Now that the peace process is proceeding, people are beginning to go back. Illegal gold mining is already taking place, which introduces mercury into the river and waterways, and into the food chain for animal life. This project is being co-ordinated by Neil Maddison, head of conservation at Bristol Zoo. Its aim is to help to preserve wildlife, flora and fauna in general, and to encourage people who go back to live in the area and companies which intend to invest in the area to observe the highest possible standards. That does not go quite as far as a national park regime—it falls a little short of that—but it would gain those companies green points. I believe that that very much is the way forward.

This is an important issue and it is a very good opportunity to ask the Government to comment on not only this trade treaty and any possible changes that could be made to it but to further push our high standards in our overseas commitments.

Lord Alton of Liverpool (CB): My Lords, it is a great pleasure to follow the noble Baroness, Lady Hooper, whose knowledge of Latin America is probably unparalleled in your Lordships’ House. She and I are both members of the All-Party Parliamentary Friends of CAFOD, for which I serve as treasurer. A few months ago, with the Labour Member of Parliament, the right honourable Tom Clarke, who chairs that group, I met a group of Colombian human rights advocates, indigenous Colombians and Afro-Colombians, who were in the UK as guests of that charity. CAFOD is also part of the coalition ABColombia, which is an alliance of CAFOD, Christian Aid, Oxfam, SCIAF and Trocaire. I was profoundly moved by the commitment of those who have put their own lives at risk in working for peace and human rights in Colombia, but also shocked by the scale and nature of some of the egregious violations of human rights which they described. I promised them that, if the opportunity arose, I would try to draw Parliament’s attention to the dangers that they faced. Therefore, I am particularly grateful to the noble Lord, Lord Stevenson of Balmacara, for moving this Motion today, which gives us the opportunity to raise questions and to do just that.

12.15 pm

Although there has been some improvement in the political and economic situation in Colombia, guerrillas and successor groups to paramilitaries have continued to be involved in significant acts of violence. Human rights defenders, trade unionists, journalists, indigenous and Afro-Colombian leaders and IDP leaders regularly face death threats, intimidation and other abuses. Although the Administration of President Juan Manuel Santos have consistently condemned threats and attacks against rights defenders, in a culture of impunity, perpetrators are rarely brought to justice. After decades of internal conflict, with 220,000 people killed, the Government are now in peace talks with the FARC guerrilla group but, with the exception of Syria, Colombia, with a phenomenal 5.7 million displaced people, has the highest number of internally displaced people in the world. As

30 July 2014 : Column GC636

the advocate whom I met explained to me, the displacements have frequently come about as a direct consequence of corporate investment, when land is wanted for agriculture, oil exploration or coal mining.

In 2011, the Colombian Government introduced a welcome law to restore to victims some of the 2.2 million hectares of the 6.8 million forcibly taken from them. To date, according to Colombia’s comptroller general, less than 1% of that land has so far been restored. The continuing conflict has also seen some victims, to whom land has been returned, once again violently displaced. According to the Colombian constitutional court, 34 groups of indigenous peoples are currently at risk of extinction. The court identified forced displacement as the major cause. Colombian indigenous peoples’ land is generally in areas rich in natural resources. To safeguard the people and the land, Colombia will need to legislate to protect them from the huge influx of multinational corporations. As I will argue, instead of protection, the UK has created in this trade treaty something that will benefit British businesses but harm exploited and vulnerable people.

It is not just the people who are at risk—it is also the people who try to protect those at risk. What happens to people who challenge rapacious business interests, international conglomerates or the warlords and guerrillas who have profiteered at the expense of the poor? I would like to give the committee an illustration. In May, Colombia’s Senate enacted an important Bill that is a major step in aiding and protecting sexual violence survivors, especially those who are raped or assaulted by guerrillas, paramilitaries, Colombian forces, or others in the context of the country’s decades-long conflict. Colombia’s new law stipulates that sexual violence can constitute a crime against humanity under the standards provided for in international law. But it is indicative of the country’s lawlessness that Ana Angelica Bello, one of the most vocal advocates of this law, died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound under circumstances that still remain unclear. Angelica, from rural Colombia, was forced off her land by armed groups. She was raped by men she believed to be former paramilitary as punishment for her subsequent advocacy and activism.

Today’s welcome debate, triggered by the noble Lord, Lord Stevenson, should ring alarm bells about human rights in Colombia and particularly alert us, as the noble Baroness, Lady Hooper, said, to the dangers faced especially by women such as Angelica and by lawyers and human rights defenders. Professor Sara Chandler, on behalf of the UK members of the International Caravana of Jurists points out that the bilateral investment treaty with Colombia ratified on 10 July is in danger of worsening the situation of human rights’ defenders. She particularly draws attention to an issue raised by the noble Lord, Lord Stevenson, about how we are going to monitor how this treaty works out in practice in future. The Caravana is comprised of international lawyers and includes judges, solicitors, barristers, academics and law students. At the request of its counterparts in Colombia, it has visited the country since 2008 and has gathered first-hand accounts of lawyers who have faced daily threats of violence, kidnapping and death just for undertaking their professional duties. Since January 2012, it has recorded

30 July 2014 : Column GC637

37 threats directed towards lawyers or human rights defenders operating as legal representatives, with 18 killings during that period. Incidentally, it will be returning to Colombia next month.

Caravana points out that the United Kingdom has significant leverage, as Britain, as we have heard, is second only to the United States in foreign investment in Colombia and that new investment treaties and fair trade agreements such as the BIT offered the opportunity—sadly, not taken—to include safeguards to ensure that British businesses investing in Colombia will never be complicit in serious human rights violations. It also points to the serious imbalance between the significant protection afforded to investors, compared to the lack of protection and resources available to the indigenous people and local communities affected by development, and states that that disparity places the United Kingdom Government in a position of direct inconsistency with their commitments under the United Kingdom action plan Good Business, which implements the Ruggie UN Guiding Principles on Human Rights.

The action plan contains a commitment that,

“agreements facilitating investment overseas by UK or EU companies incorporate the business responsibility to protect human rights, and do not undermine the host country’s ability to meet its international human rights obligations”.

The bilateral treaty with Colombia remains, ominously, completely silent about those responsibilities. Why is that? This is one of the first tests of whether the sentiment and rhetoric will be matched by the reality. Therefore, it does not bode well. Are we to be simply what John Ruskin once described as a “money-making mob”?

Specifically, in the peace talks in which the Colombian Government are engaged in, they have committed themselves to the land reforms to which the noble Lord, Lord Stevenson, referred. Have the Government discussed what impact the treaty will have on the Colombian Government’s ability to return land and to implement the Havana agreement on land reform? Will the Minister, the noble Lord, Lord Livingston of Parkhead, also confirm that the largest UK investments in Colombia are in mining, with all the land requirements which mining entails? Will he also tell the Committee how much of the land violently seized and confiscated in Colombia’s conflict is in areas rich in natural resources and on land owned by indigenous peoples, Afro-Colombians and peasant farmers who are waiting for their land to be restored—the people I referred to at the outset of my remarks? Will he explain to the Committee how restoration is compatible with pursuing Britain’s mining interests, and which will take precedence—as if we do not already have a hint as to the answer? Will he also say how we will guarantee the rights and obligations to which I referred of indigenous peoples in respect of their free, prior and informed consent, their right to self-determination and to their own development, which are guaranteed in United Nations International Labour Organization Convention 169 and the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples?

Are we simply to be a money-making mob, or will the Government insist that human rights which we expect for ourselves will be applied in situations where

30 July 2014 : Column GC638

our monetary clout gives us influence and leverage? It is really unacceptable that we have created a self-serving agreement which incorporates a disparity in providing considerable—some would say, excessive—protection for British investment while the ability of the Colombian state to regulate that investment is restricted. The investor-state dispute settlement provisions could have been used as an opportunity to incorporate human rights provisions and to enable a third party, such as an NGO, to make representations in the dispute process. As things stand, the UK-Colombia BIT has no such safeguard. We could do a lot worse than emulate the EU-Canada free-trade agreement, CETA, which incorporates safeguards affirming the right of states to regulate in pursuance of legitimate public interest objectives.

In another context, the House of Lords EU Committee has expressed doubts about including an investor-state dispute settlement that gives investors the right to challenge measures adopted—in this case, by the UK—in the public interest. The committee recommended that before including an ISDS clause, a number of safeguards should be in place, including to,

“improve transparency around ISDS proceedings, for example by making hearings and documents public, allowing interested third parties to make submissions”.

Those safeguards do not seem to form part of the bilateral investment treaty with Colombia.

To conclude, I therefore ask the Minister: what plans the Government have to incorporate safeguards to the investor-state dispute settlement provisions in the treaty to enable the UK to ensure that its foreign investments do not make us complicit in serious human rights violations? At the very minimum, will the Government consider creating a system of annual monitoring of the treaty in terms of its human rights impacts and impact on the peace agreements, with the results to be incorporated in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office annual human rights report? What plans are there to incorporate safeguards to the investor-state dispute settlement provision, to ensure that the United Kingdom complies with its human rights obligations and commitments made in Good Business on implementing the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights?

Colombia is listed as one of the countries of concern in the annual FCO human rights report. Instead of promoting policy changes to improve human rights, the bilateral agreement could obstruct Colombia’s ability to promote policies that achieve improvements in human rights. Given the record levels of UK investments in Colombia, there was simply no need for this treaty in the first place. Ministers should give further thought to the consequences of its ratification, along with the ethical implications of its promotion.

Lord Monks (Lab): My Lords, I start by declaring an interest. I am vice-president of Justice for Colombia and play an active role and take an active interest in that country. I also thank my noble friend Lord Stevenson for having the wit to initiate this debate on something that should not go through Parliament quietly in a way that has hitherto been the case. I share the concerns about this treaty expressed by all previous speakers. I am first rather puzzled about why it is so necessary, especially in view of the EU-Colombia trade talks

30 July 2014 : Column GC639

which have been going on. In a previous life, when I was general-secretary of the European trade unions in Brussels, I was involved in making sure that social and environmental concerns were properly covered in that arrangement.

This rather more liberal agreement—liberal in the economic sense—sits oddly with the EU trade treaty. As has been said, Colombia remains a dangerous place for many of its citizens, including many from the trade union world. Until recently, it was the most dangerous place in the world to be an active trade unionist, at risk from one or other groups of paramilitaries. In 2013, 78 human rights activists were killed, an increase over the previous years. The Colombian Government are active in saying that things are getting better—we hope they are—but the past year has seen a lot of trouble, with mass unrest and big strikes across the country. These have been particularly in the agricultural sector, where there have been serious clashes with the police, with 27 dead just last summer.

I want to see the Colombian peace talks do well in Havana. The peace process there draws some useful lessons from our experiences in Northern Ireland. However, as the noble Lord, Lord Alton, said, Colombia has the largest number of displaced people in the world, according to the UNHCR, largely the result of land-grabbing by various paramilitary-backed forces. This brings me to the new treaty protecting foreign firms which invest from the danger of expropriation or other changes which might damage their investment. What could sound more benign than that? Except that Colombia is not a benign place—it is still in turmoil and this need, in terms of the peace process, to restore at least 2.5 million hectares of land to people from whom it has wrongly been taken seems to sit awkwardly with the provisions of this treaty. The treaty could make it a lot harder to restore land to those who originally owned it: for example, where stolen land has been sold to a Western company. What does the treaty have to say about that? Where is the balance of advantage and whose interests will predominate in those circumstances? I would be very interested to hear the Minister’s views on that problem.

The risk that this could limit the application of the peace agreements is considerable. Everyone needs to remember that paramilitaries continue to operate, even though the peace talks are under way. The implication in this of putting British investment interests above human rights and possibly even above that peace process sends a very serious message. I hope that the Government will find ways, as has been suggested by my noble friend Lord Stevenson and others, to reflect on the application of this agreement, even if it is too late to change it.

12.30 pm

The Lord Bishop of Sheffield: My Lords, I shall speak briefly to support and echo the excellent remarks of the noble Lord, Lord Stevenson, and the points made by other noble Lords on the dangers posed by this treaty, in three specific areas.

First, on the protection of land ownership rights, as we have heard, this is no small issue in Colombia. A concern for the common good of the international

30 July 2014 : Column GC640

community must surely include ensuring the ability of Colombia to continue to regulate in the interests of its own people, especially on this key issue. Such a concern would clearly preclude the binding of the Colombian people to corporate rather than national interests. We must therefore work to achieve greater reciprocity in the balance of protections afforded to investors, the Colombian Government and the wider citizenry, including the indigenous peoples in respect of land ownership rights. To this end I, too, urge the Government to incorporate safeguards to the investor-state dispute settlement provision to ensure that the UK complies with its human rights obligations and commitments made in

Good Business: Implementing the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights

.

Secondly, I wish to echo the excellent remarks of the noble Lord, Lord Stevenson, on the dangers posed by this treaty to the protection of the human rights of the Colombian people. Assurances are needed from the Government that the necessary changes will be undertaken to ensure that the treaty does not undermine Colombia’s ability to meet its international human rights obligations. This is particularly necessary with respect to upholding the indigenous peoples’ right to free, prior and informed consent, and their right to self-determination and their own development, as guaranteed in the United Nations ILO Convention 169 and the treaty on the rights of indigenous peoples.

Thirdly, I strongly urge the Government to establish an annual monitoring system for the treaty, to measure the impact of this agreement on both human rights and peace agreements. In the interests of accountability, as has been suggested, such monitoring ought to be incorporated into the annual FCO human rights report.

The Minister of State, Department for Business, Innovation and Skills & Foreign and Commonwealth Office (Lord Livingston of Parkhead) (Con): My Lords, I thank the noble Lord, Lord Stevenson, for proposing this debate and I thank other noble Lords, particularly on the last day of the session, for their contributions. I know that many in this House take a close interest in Colombia, the progress that that country has made and the challenges it has faced over recent years. As I think noble Lords will be aware, this matter has also been debated in the other place.

I make it clear at the outset that the Government believe that the UK-Colombia investment treaty will benefit both countries. It will encourage increased levels of investment that will contribute towards economic growth, which I believe is in everyone’s interests. This view is shared by the democratically elected Colombian Government. They ratified this treaty in 2013 and have been pressing since then for the UK to ratify it as soon as possible. They have stated that they believe it will stimulate investment flows, guarantee the transparency and protection of investments within the standards recognised by international law, strengthen Colombia’s commercial ties with the rest of the world and guarantee equal treatment to Colombian investors in the UK.

In the next few years, there will be significant investment opportunities in Colombia in sectors where British companies are world leaders, including infrastructure, extractives, education, science and innovation. With the investment treaty in place, I

30 July 2014 : Column GC641

believe that British companies are more likely to invest in projects which will help to deliver the right answer for Colombia. Colombia has investment treaties with many other major trading partners, including the US, China, India and Spain. They have also recently reached an agreement with France and it is right that UK investors should enjoy similar protections.

A number of concerns have been expressed in this debate and in other fora. I believe that some fears are exaggerated, but I understand them. First, it is suggested that the treaty will harm Colombia by impacting on the ability of the Colombian Government to regulate because of the risk of having to compensate investors who may bring compensation claims under the agreement, particularly through the ISDS clause, which has been mentioned.

Before I deal with individual questions, some facts are useful. For example, the UK has 94 such agreements. In aggregate, if you add them all together, they have been in existence for more than 2,000 years. There have been two cases and neither of them have been successful. The point about ISDS clauses is that they kick in only when there is not sufficient domestic process to deal with such matters. ISDS clauses are instead of adequate domestic processes. In that context, it is worth pointing out that I do not believe that Colombia has ever faced an ISDS claim.

However, despite the fact that history tells us that that is not a route for corporates to override domestic policy—a view that many have expressed—we have sought to modernise the ISDS clause to protect the state. Several noble Lords have mentioned TTIP and CETA. Although this agreement was made before they were, it contains many of the items raised in relation to TTIP. We cannot replicate the TTIP clause—not least because the TTIP clause does not exist. In fact, there is some debate in the EU whether there will ever be an ISDS clause in TTIP. I think that there may well be.

I would like to go through some of the protections in the treaty. First, it excludes shell companies from investment protection. That is important because some of the more egregious uses of ISDS clauses between third-party countries have been through the use of shell companies. There are also measures to prevent vexatious or frivolous claims. The scope of what is deemed to be fair and equitable treatment is limited; that is important. Indirect expropriation is explicitly defined; I will mention that later in relation to public policy matters. Investors must pursue resolution through the domestic legal system first for six months before submitting the claim. Having read through the treaty again, it aims to cover many of the issues raised.

Taken as an overall package, this is designed to discourage speculative claims. The Colombian Government and the UK Government negotiated it at some length. Investors should rightly have grounds for a claim if they have suffered discriminatory and genuine mistreatment. It has been used in other countries in that manner. By prioritising domestic resolution, ISDS itself would represent a last resort.

The noble Lord, Lord Alton—and, I think everyone else—raised issues about human rights. Of course, in Colombia, this issue is complex and difficult. The

30 July 2014 : Column GC642

Government recognise the progress that the Colombian Government have made in tackling human rights issues, but clearly they are not there yet. There are still challenges and more that can be done to improve the situation in Colombia, especially for human rights defenders, victims and land restitution claimants and to prevent sexual violence. The UK Government will continue to discuss the matter and raise it with the Colombian Government.

The continuing armed conflict is one of the major issues—

Lord Alton of Liverpool: Before the Minister leaves that point about monitoring the situation, several noble Lords suggested having a formal mechanism in the department and within the Foreign and Commonwealth Office to log each year our assessment of human rights in Colombia and how they are being impinged on by business interests. Will he do something more formal than simply saying that it is an issue that concerns the Government?

Lord Livingston of Parkhead: I was going on to talk about the FTA, which covers a number of human rights issues and discussions. I will discuss with my colleagues in the Foreign Office the monitoring and reporting of human rights in Colombia as a more general issue. It is clearly one area of the world—regrettably, there are many—which has been a challenge.

The armed conflict is one of the main sources of the problems in Colombia. Like the noble Lord, Lord Monks, I support the efforts of the Colombian Government to find a solution through a negotiated peace process. Three or four months ago, I was in Colombia and had discussions with the Colombian Government. I do not doubt their genuine approach to finding a peace solution. In many cases, they will have to take some of the people of Colombia with them during this process. Some have made the corollary with some of our efforts in Northern Ireland and there is, of course, a lot of hurt over the years to make up. I hope that they make progress, which would lead to a number of better solutions.

The UK Government take a balanced approach. We realise that there are problems. It is very important to recognise the progress and effort of this Government in Colombia. They have made significant progress and we will continue to urge them to make further progress. We will also raise specific issues, and will urge that appropriate investigations take place and that protection measures are afforded.

The noble Lord, Lord Alton, and others raised land reform. We do not agree that the treaty presents a threat to Colombia’s land restitution programme. As noble Lords know, under the programme, businesses can lose their land, or have to pay compensation, if they cannot prove they undertook due diligence to ensure that the previous occupants were not forcibly displaced. However, in practice, the risk of a business owned by a UK investor losing land or having to pay compensation appears to be small. Very few businesses appear to be losing land and we are not aware of any claims against British businesses under the programme.

I support the concerns expressed by the noble Baroness, Lady Hooper, and the noble Lord, Lord Alton, and

30 July 2014 : Column GC643

others that it is very important for British companies to observe international standards, such as those set out by the UN and the OECD. That is reflected in the EU-Colombia FTA, signed in 2012, which is much more the current state of the art. It contains significant commitments relating to human rights, labour rights, environmental protection and sustainable development. The Government also have an existing dialogue with the Colombian Government on these matters.

In view of this, reopening the treaty negotiations would be somewhat superseded by the EU-Colombia FTA. It would lead only to an unnecessary delay in bringing the treaty into force. I must stress that the treaty would be good for Colombia as well as for the UK. I do not believe that reopening the negotiations would add value on human rights. I am also unclear whether an investor could make a claim under the treaty that is in a way detrimental to human rights. The Government are not aware of any cases involving UK investors under any of our 94 treaties.

On the contrary, it is arguable that any state actions which may breach an investment treaty by harming an investor are more likely to damage local communities given the economic benefits, including employment and generating tax revenues, which stable, responsible—I believe that UK companies are responsible—foreign investment delivers.

Environmentally, Colombia is one of the top ecological hotspots in the world. I think that the noble Baroness, Lady Hooper, also mentioned Brazil. I thought that there would be nothing better perhaps than to read the clause relating to the environment in the bilateral agreement, which states:

“Nothing in this Agreement shall be construed to prevent a Party from adopting, maintaining, or enforcing any measure that it considers appropriate to ensure that an investment activity in its territory is undertaken in a manner sensitive to environmental concerns, provided that such measures are non-discriminatory and proportionate to the objectives sought”.

That seems like a reasonably balanced approach to environmental concerns.

In a similar way, on public interest concerns, the same issues have been raised in relation to TTIP. In relation to indirect expropriation, which usually is the basis on which people worry about these clauses, the agreement clearly states:

“For the purposes of this agreement, it is understood that … non-discriminatory measures that the Contracting Parties take for … public purpose or social interest … including for reasons of public health, safety, and environmental protection, which are taken in good faith, which are not arbitrary, and which are not disproportionate in light of their purpose, shall not constitute indirect expropriation”.

I am struggling to understand some of the claims that have been made regarding this treaty. It is a modern addition to historic bids and ISDS. As I said, it was debated between the individual parties. While events in some ways have overtaken it with the FTA, the UK-Columbia investment treaty is still an important milestone in the development of our wider trade and investment relationship. The growth and success of Columbia on a wider scale will be important. It was negotiated and supported by the democratically elected Government of Colombia. It will encourage UK investors to do further business in the region that will be to the

30 July 2014 : Column GC644

benefit of the Colombian people. It will contribute to Columbia’s economic development through the benefits that increased levels of investment will bring. I strongly believe that we should welcome it and the benefits and safeguards that it will bring to the people of both countries.

12.45 pm

The Deputy Chairman of Committees: The Question is that this Motion be agreed to—

Lord Stevenson of Balmacara: I think that we might have made a small technical error in procedure. I want to say a few words in response and draw a few things together. I am sorry if this is confusing. I am new to this as well as everyone else, and I am looking round for somebody with expertise in this area .

If I may, I shall make a short statement. Let us restart: it is like being in the film “Groundhog Day”, when we keep coming back to the same point, except that we have not. I thank all speakers for their contributions. The knowledge and expertise that has been displayed has been very good and appropriate for the debate. I also think that it is important to recognise that we had Conservatives, Labour Members, Cross Benchers and Bishops representing us, so all aspects of the House have been recorded. The unanimity in what was being said was remarkable. I acknowledge that we are in a situation that is slightly perverse in the sense that the treaty has already been enacted and we are not in the position of asking the Government to reconsider it.

However, some points might be taken forward for future debates and I want to come back to that at the end. We are all very concerned about the way in which human rights need to feed into these treaties nowadays. There are reasons why it did not happen at this stage, but I do not see why that should necessarily be the case going forward. It is also the case that the FTA contains a significant proportion of human rights issues, but that was an EU treaty and not an individual country-to-country one. Therefore, the message is there for the Minister to take back that in future this House might expect to see a stronger and tougher section on human rights.

I thought that the point about corporate social responsibility and the need to build on that was very well made by the noble Baroness, Lady Hooper; we should record that as something that should go forward. Specific important issues in relation to this treaty were touched on in terms of reporting and because of the current situation with FARC. The noble Lord, Lord Alton, made a good point when he said that the sentiment and rhetoric on display today should be matched by concrete words. That is an important point. The Government are not quite in the same place as the sentiment in the House in relation to how we reflect concerns about ISDS and human rights.

The noble Lord, Lord Monks, was right in saying that the wording is rather awkward in relation to the situation that we see on the ground, particularly in relation to the number of people who are dispossessed from their historic rights to land. The only response we got from the Minister was that he understood our

30 July 2014 : Column GC645

fears but thought they were overstated. I do not think that that cuts it. If he is going to rely on the fact that ISDS is merely a fall-back, and that the right solution to disputes arising from these treaties is to strengthen the domestic legislative processes, we also need to know what the Government are doing to help that. He did not say that, and it is an important point.

Although, as I have said, human rights issues were not in play in such a position in 2008-09, when this treaty commenced, they certainly are now. It seems a curious logic to say that there will be sufficient other activity going on when the wording already exists in the FTA and could be used in future. I hope the Government will give us a firm commitment at some point in the appropriate way to take this issue forward, so that we have a set of words which mean what they say in relation to our commitments—shared around the House—to human rights in these areas. This is especially where there are particular circumstances that are being discussed with FARC.

Having said that, this Motion was an attempt to get a debate and discussion, which it has succeeded in doing.

Motion agreed.