“Long overdue statement and a very welcome one. It is abhorrent in the 21st century that any human being should be seen as an untouchable.” -Alton

| Dalit Christians face discrimination and untouchability, admits Indian Catholic Church – Firstpost www.firstpost.com A policy document released by the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of India (CBCI) contained admissions of the Indian Catholic Church accepting for the first time in history that Dalit Christians face discrimination and untouchability |

http://www.firstpost.com/india/dalit-christians-face-discrimination-and-untouchability-admits-indian-catholic-church-3157454.html

http://indianexpress.com/article/india/church-says-dalit-christians-face-untouchability-discrimination-4427658/

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON DALITS & CASTE DISCRIMINATION: February 2014, London.

Also see article (page 30 ) Justice Magazine, Spring Edition:

http://www.justicemagazine.org/jm/index.php/read-the-magazine

David Alton – Professor the Lord Alton of Liverpool.

Make Caste History

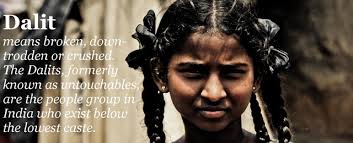

On a visit to West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh and Delhi I spoke about the plight of India’s untouchables, the Dalits, and the forms of exploitation and slavery which stem from the caste system. Dalit is a term which derives from a Sanskrit word meaning “broken” or “crushed”.

200 million Dalits in India make up one sixth of India’s population and one thirty fifth of the world’s population. Dalits live in 132 countries, including countries like the UK, where South Asians have migrated.

Take Dalits and Tribals together, both of whom fall outside the caste system and experience discrimination: they comprise a quarter of India’s population and one twenty fourth of the world’s population.

Lest you think that these are historic questions let me make absolutely clear that hardly a day passes without some new horror perpetrated against the Dalits.

These are just some of stories taken from the Indian newspapers in the last seven days: Dalit woman burnt by employer for resisting rape in Bulandshahr- India Today; 5 held for gang rape of dalit girl near Dindigul- The Times Of India; Dalit woman assaulted, stripped in Hassan village- The Hindu Dalits, death and the fight for dignity – DNA; Dalit women in Haryana to march for redressal of cases of atrocities committed by upper caste men- Two Circle; Dalit Beaten Up for Touching Caste Hindu- The New Indian Express; Children protest against discrimination at school- The Hindu; No clean water for Dalits?- Kashmir Times; Sorcery slur on Dalit family- The Times Of India; Over 39,000 cases filed under Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes Act in 2012: Business Standard

Two hundred years ago, on 22 June 1813, six years after he had successfully led the parliamentary campaign to end the Trans Atlantic Slave Trade, William Wilberforce made a major speech in the House of Commons about India.

He said that the caste system,

“must surely appear to every heart of true British temper to be a system at war with truth and nature; a detestable expedient for keeping the lower orders of the community bowed down in an abject state of hopelessness and irremediable vassalage. It is justly, Sir, the glory of this country, that no member of our free community is naturally precluded from rising into the highest classes in society”.

Two centuries later the caste system which Wilberforce said should be abolished – and which the British during the colonial period signally failed to end – still disfigures the lives of vast swathes of humanity.

India’s Prime Minister, Dr Manmohan Singh has trenchantly and rightly argued that, “untouchability is not just social discrimination; it is a blot on humanity”.

Today, I would like to pay particular tribute to some of those who work tirelessly to combat caste, especially the work of Voice of Dalit International and the Dalit Freedom Network, particularly its international President Joseph D’Souza – whom I first met after he had joined forces, in 2006, with other Christian leaders after five Dalits were lynched for skinning a dead cow.

In New Delhi those leaders joined a protest, met the parents of the victims and provided their families humanitarian assistance. Dr.D’Souza said: “The statement we were making was that these Dalits were human beings, and that it was the caste system that consigned them to work with animals—a statement in direct contrast to that of a Hindu nationalist leader, who said that a cow was more valuable than a Dalit.”

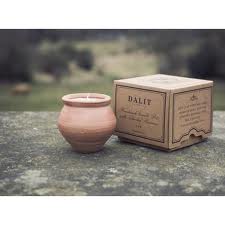

In my study at home in Lancashire, I have a small terracotta pot given to me by Dr D’Souza. Such pots must be broken once a dalit has drunk out of them so as not to pollute or contaminate other castes. This is the 21st century. It is not the pots which need to be broken, not the people, but the system which ensnares them.

Dr D’Souza rightly says:

“If we are not intentional about bringing change and transformation in lives and society it will not happen. To love people is to act on behalf of them”.

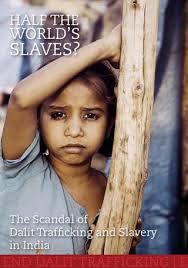

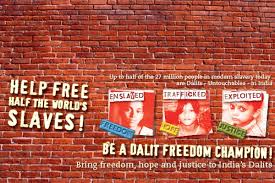

As Parliament considers the new Bill on modern slavery, reflect that the Global Slavery Index, published in October last, confirmed that around half of the world’s slaves are in India – some 13.9 million out of a global total of 29.8 million, and that most of them are Dalits or Tribals. In the Hindu caste system, they are regarded as subhuman—lower even than animals and left fighting a largely unknown struggle for emancipation.

Evidence points to 80-95% of bonded labourers (the vast majority of the ‘modern slaves’ in India) being Dalits, 99% of ritual sex slaves (the 250,000 temple prostitutes known locally as Devadasi or Jogini) being Dalits, and the majority of those trafficked into brothels or into domestic servitude being Dalits or Tribals.

If you are a Dalit in India you are 27 times more likely to be trafficked or exploited in another form of modern slavery than anyone else. Much of this is brilliantly documented in Dalit Freedom Network’s booklet, “Half the World Slaves?”

According to CNN, India’s former Home Secretary, Madhukar Gupta, “remarked that at least 100 million people were involved in human trafficking in India”, whether for sex or for labour.

The head of the Central Bureau of Investigation said that India occupied a unique position as a source, transit and destination country for trafficking, and that it has more than 3 million prostitutes, of whom an estimated 40 per cent are children. These statistics are hugely significant: the situation in India simply must be at the heart of the global fight against trafficking

Caste should be recognised as a root cause of trafficking, of modern day slavery and poverty and unless we raise the profile of the oppressed Dalits nothing will change.

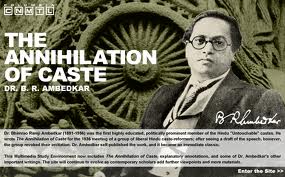

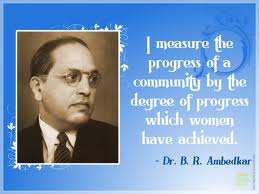

To prepare me for this conference, Voice of Dalit International were good enough to send me a copy of Dhananjay Keer’s admirable biography of Dr.Babasaheb Ambedkar who was born into a family of untouchables in 1891.

When Dr. Ambedkar died on December 7th, 1956, Prime Minster Nehru adjourned the Lok Sabha for the remainder of the day having told parliamentarians that Ambedkar had been controversial but had revolted against something which everybody should revolt against – all the oppressing features of Hindu society.

Dr. Ambedkar, the architect of Indian Constitution once remarked that “Untouchability is far worse than slavery, for the latter may be abolished by statute. It will take more than a law to remove the stigma from the people of India. Nothing less than the aroused opinion of the world can do it”

that “Untouchability is far worse than slavery, for the latter may be abolished by statute. It will take more than a law to remove the stigma from the people of India. Nothing less than the aroused opinion of the world can do it”

Ambedkar’s life was a life of relentless struggle for human rights. Born on a dunghill and condemned to a childhood of social leprosy, ejected from hotels, barber shops, temples and offices; facing starvation while studying to secure his education; elected to high political office and leadership without dynastic patronage; and to achieve fame as a lawyer and law maker, constitutionalist, educator, professor, economist and writer, illustrates what the human spirit can overcome.

In 1927, the young Ambedkar famously led a march to the Chavdar reservoir, a place prohibited to Dalits. On arriving at the reservoir, he bent down, cupped his hands, scooped up some water, and drank—an act completely forbidden by the caste system. The Brahmins, or upper castes, responded by furiously pouring 108 pots of curd, milk, cow dung, and cow urine into the reservoir – a ritual act which they claimed would “purify” the water polluted and defiled by untouchables.

Ambedkar could so easily have taken the path of violent revolution, spurred on by bitter hatred or a need for revenge – but although others regarded his shadow as a sacrilege and his touch as a pollutant, he demonstrated why it is the caste system which deserves to be put beyond human touch not the men, women and children condemned by it.

Ambedkar made untouchability a burning topic and gave it global significance. For the first time in 2500 years the insufferable plight of India’s untouchables became a central political question. Among untouchables themselves he awakened a sense of human dignity and self respect. He repudiated the helplessness of fate, the impotent, demoralised incapacity that insisted that everything is pre-ordained and irretrievable.

Ambedkar made untouchability a burning topic and gave it global significance. For the first time in 2500 years the insufferable plight of India’s untouchables became a central political question.

He began a war against a social order that allowed caste to condemn millions to a life of irreversible servitude and social ostracism. This was an existence he had shared. “You have no idea of my sufferings” he once said. Having personally experienced life below the starvation line, the effects of destitution and squalor, the humiliation of ejection, segregation, and rank discrimination, “having passed through crushing miseries and endless trouble” Ambedkar determined to challenge these evils by entering political life: becoming renowned as a scholar-politician, sadly, a combination so little in evidence today.

Ambedkar understood that the great nation of India would never achieve its potential if it remained disfigured and divided by caste. Without freedom to marry, who they would; to live with, who they would; to dine with, who they would; to embrace or touch, who they would; or to work with, who they would, the nation could – and can – never be fully united or able to fulfil its extraordinary potential.

“the roots of democracy” are to be found “in social relationships and in the associate life of the people who form the society.” He said that “if you give education…the caste system will be blown up. This will improve the prospect of democracy in India and put democracy in safer hands.”

He believed that “the roots of democracy” are to be found “in social relationships and in the associate life of the people who form the society.” He said that “if you give education…the caste system will be blown up. This will improve the prospect of democracy in India and put democracy in safer hands.”

Education is still the best hope for social transformation. Once people are empowered by education – as Ambedkar was himself – they can begin to address issues of poverty, lack of dignity, discrimination and other dehumanising attitudes. Do not underestimate the power of good quality, English-medium education taught from a worldview that emphasises values such as dignity, equality, acceptance, human worth, and self-esteem. I say English-medium because this is the preserve of high castes, and it is still the language of opportunity – the language of higher education, government, and commerce.

Once people are empowered by education – as Ambedkar was himself – they can begin to address issues of poverty, lack of dignity, discrimination and other dehumanising attitudes

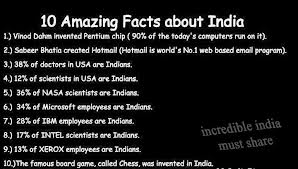

India is to be admired for providing near-universal education, and there has been a rise from 7 per cent to 13 per cent in those entering higher education, but many agree that teaching remains poor and only 20 per cent of job seekers have any vocational training.

Even these opportunities tend to be denied to the dalits and the 84 million tribal people, who suffer discrimination and marginalisation. This vast expanse of humanity, trapped in a time warp, appears wholly unconnected to and at variance with India’s sophisticated economic and technological advances—and is certainly at variance with the advertising slogans, “Amazing India” and “Incredible India”.

What is truly amazing and incredible in this day and age is that “the cruel shackles” of the caste system, this “detestable expedient … a system at war with truth and nature” should persist in 2014.

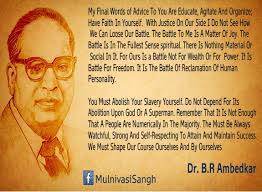

While still a young man of twenty, Ambedkar perceptively wrote: “Let your mission be to educate and preach the idea of education to those at least who are near to and in close contact with you.” He said that social progress would be greatly accelerated if female and male education were pursued side by side. He later insisted that “We will attain self elevation only if we learn self-help, regain our self-respect, and gain self knowledge.”

He supported Britain’s war effort against the Nazis because he said it was a war between democracy and dictatorship. He linked it to the battle for the removal of caste: “the battle is in the fullest sense spiritual…it is a battle for freedom. It is a battle for the reclamation of the human personality.” He told his audience to “educate, agitate and organise.”

While still a young man of twenty, Ambedkar perceptively wrote: “Let your mission be to educate and preach the idea of education to those at least who are near to and in close contact with you.” He said that social progress would be greatly accelerated if female and male education were pursued side by side. He later insisted that “We will attain self elevation only if we learn self-help, regain our self-respect, and gain self knowledge.”

He said dalits should “educate, agitate and organise.”

Ambedkar rightly perceived the negative effects which caste has on economic development – and in his booklet “Annihilation of Caste” he argued that caste deadens, paralyses and cripples the people, undermining productive activity by frequently denying opportunities to those with natural aptitude and through the entrenchment of servitude. Caste amounts to the vivisection of society.

Ten years ago the deadening effects of caste were recognised by the Department for International Development (DFID).

In a Policy Paper they stated that ‘Caste causes poverty’, and ‘gets into the way of poverty reduction’; that caste ‘ reduces the productive capacity and poverty reduction of a society as a whole’; and that ‘poverty reduction policies often fail to reach the socially excluded’, Dalits ‘unless, they are specifically designed to do so’.

Yet these clear and coherent priorities scandalously failed to make any appearance whatsoever in the Millennium Development Goals and although the post-2015 High Level Panel Report, chaired by David Cameron, does include a section on “Other Vulnerable Groups” and the one group mentioned by name are the dalits, we need to say and do far more. The Panel was right to argue that there is a need for “Legislative and institutional mechanisms to recognise the indivisible rights of indigenous peoples, ethnic minorities, dalits and other socially excluded groups must be put in place” but how is that reflected in our day to day priorities, diplomacy and policies?

Dalits constitute 40% of the global poor and are denied of DFID Funding, because they largely live in India, which simply doesn’t make the policy priorities. This becomes a new form of untouchability.

One development worker, with 14 years experience of working among Dalits, says that “95% of development time, energy and resources are wasted on combating … a ‘general Caste mindset’…stipulating how different segments of caste based society should live as touchables or untouchables, humans or sub-humans. The whole life of more than 50% of the population, from morning till night, from birth to death, is predetermined.”

In India you can’t make poverty history unless you make caste history. As we examine what has been achieved through the MDGs and the plight of the global poor the professional development agencies need to take a long hard look at the way they target poverty. As they think beyond 2015 they need to listen, rather than impose, and develop a cross thematic framework for addressing the curse of the caste system.

The churches, too, need to play a more decisive role in recognising the existence of caste and its consequences – in India but in the UK too, where 50% of our estimated 1 million Dalits are considered to be poor.

Some of these agencies need to radically rethink their mindset and priorities. They will be far more effective in tackling poverty if they tackle social exclusion. The churches, too, need to play a more decisive role in recognising the existence of caste and its consequences – in India but in the UK too, where 50% of our estimated 1 million Dalits are considered to be poor.

Ambedkar also saw the role which religion could play in shaping attitudes and behaviour. He repudiated Marxist atheism and refused to be forced into a repudiation of religious faith because of its distortions. But he was scathing when he saw religion as a cause of human suffering.

He attacked Hindu priests who refused admission to Dalits to their temples and was scathing about those Christian churches which had imported the caste system into the segregation of believers. And of Islam he said:

“The brotherhood of Islam is not the brotherhood of man. It is the brotherhood of Muslims for Muslims only. For non Muslims there is nothing but contempt and enmity.”

He said that from his study of comparative religion there were two personalities who could captivate him – the Buddha and Christ.

Towards the end of his life he would convert to Buddhism as a protest against the failure of Indian religious leaders to reject the caste system and insisted that the spiritual dimension of mankind is bound up with 1) the sanction of law and morality (“without either society is sure to go to pieces”) ;2) that religion must be in accord with reason; 3)that religion must recognise the fundamental tenets of liberty, equality, and fraternity; and 4) that religion must not ennoble poverty.

Pope John Paul II said: “Any semblance of a caste-based prejudice in relations between Christians is a countersign to authentic human solidarity, a threat to genuine spirituality”

In considering their response to caste and the Dalits any Christian from the Catholic tradition, or those running Church agencies, should ponder carefully the words of Pope John Paul II:

“At all times you must continue to make certain that special attention is given to those belonging to the lowest castes, especially the Dalits. They should never be segregated from other members of society. Any semblance of a caste-based prejudice in relations between Christians is a countersign to authentic human solidarity, a threat to genuine spirituality, and a serious hindrance to the Church’s mission of evangelisation.”

Let them also reflect that violence against Dalit Christians has intensified in recent years.

Violence against Dalit Christians has intensified in recent years.

In 2008, two women—one of whom was seven months’ pregnant—were gang-raped in Nadia village, Madhya Pradesh

In 2008, two women—one of whom was seven months’ pregnant—were gang-raped in Nadia village, Madhya Pradesh. The village leader ordered the act after the women’s husbands refused to renounce their Christian faith. On January 16, 2006, Christian homes were set on fire in Matiapada village, Orissa. Instead of the arsonists being brought to justice, the Christians were imprisoned for nine days under the state’s anti-conversion law.

Through Dr.Ambedkar’s colossal labours caste began to decay but even now it has not died. On April 29th 1947 the Constituent Assembly of India declared “Untouchability in any form is abolished and the imposition of any disability on that account shall be an offence.” The New York Times compared it with the abolition of slavery and the freeing of the Russian serfs. The News Chronicle in London praised it as one of the greatest acts in history.

Although untouchability was barred by the constitution, the system was not dismantled. Most of the worst forms of exploitation are proscribed by statute, but all too often the laws are simply not implemented and the police further entrench, rather than protect against, caste prejudice.

This point was made repeatedly in the concluding observations of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination in May 2007.

“The Government of India’s continued ignorance about the depth of the problem and inadequacy in addressing untouchability and meeting its legal obligations in regard to the abolition of untouchability”.

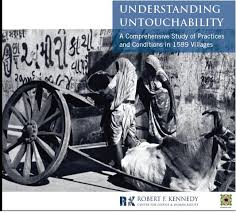

A damning verdict was reached also by an in-depth report by the Robert F Kennedy Centre, entitled Understanding Untouchability: A Comprehensive Study of Practices and Conditions in 1,589 Villages. It describes,

“The Government of India’s continued ignorance about the depth of the problem and inadequacy in addressing untouchability and meeting its legal obligations in regard to the abolition of untouchability”.

Some individual dalits have reached high positions in Indian society, not least Justice K G Balakrishnan, who rose to become the senior judge of India’s Supreme Court, and Ms Meira Kumar, who became the Speaker of the Lok Sabha, the lower House of India’s Parliament. But these are exceptions. As I heard first hand from dalits I met in India even where they are securing some kind of elementary education the opportunities for educational progress later and employment opportunities are all to frequently still blocked to them.

Consider for a moment what must be one of the most appalling and disgraceful forms of labour anywhere in the world, known euphemistically as manual scavenging. It involves cleaning human excrement from dry latrines and is uniquely performed by dalits as a consequence of their caste. The number engaged in this occupation is not known for certain, but it may be as high as, or higher than, the equivalent of the population of Birmingham.

Manual scavenging involves cleaning human excrement and is uniquely performed by dalits as a consequence of their caste. The number engaged in this occupation is not known for certain, but it may be as high as, or higher than, the equivalent of the population of Birmingham.

Tens of millions of India’s citizens are subject to many forms of highly exploitative forms of labour and modern-day slavery. This often plays into the problem of debt bondage and bonded labour, which affects tens of millions. It perpetuates a cycle of despair and hopelessness, as generations are bonded to the family debt, unable to be educated and unable to escape. Tragically, the debt is often the result of a loan taken out for something as simple and essential as a medical bill.

Caste perpetuates a cycle of despair and hopelessness, as generations are bonded to the family debt, unable to be educated and unable to escape

At times, Britain and India have had a turbulent relationship; but what is often called “the idea of India” is one that continues to captivate and enthral anyone who has been fortunate enough to travel there.

“The idea of India” is one that continues to captivate and enthral anyone who has been fortunate enough to travel there.

In 1949, India and Britain were founding members of the Commonwealth, which exists to promote democracy, human rights, good governance, and the rule of law, individual liberty, egalitarianism, free trade, multiculturalism and world peace. Britain and India are democratic nations with many shared values as well as significant common economic and security interests. Bilateral trade is worth more than £13 billion annually. Our cultural, sporting, linguistic and historic links—some of which have required colonial ghosts to be laid to rest—underline the values that bind us together.

In 1949, India and Britain were founding members of the Commonwealth, which exists to promote democracy, human rights, good governance, and the rule of law, individual liberty, egalitarianism, free trade, multiculturalism and world peace. It unites us in so many things – including a love of sport.

Yet, in 2014, while India is a rising world power and is rightly gaining a reputation for innovation and excellence in many fields, what its Prime Minister calls a “blot on humanity” disfigures India’s reputation and has become one of the world’s greatest human rights challenges.

Millions of people remain imprisoned by the bondage of what Wilberforce described as “the cruel shackles” of the caste system. Those shackles inevitably lock their prisoners into the most menial forms of labour, trap them in servitude and leave them susceptible to innumerable forms of exploitation.

And consider the people who are represented by the statistics.

Dr.Ambedkar wanted dalit women to receive education. It is estimated that every day three dalit women are raped; dalit women are often forced to sit at the back of their school classrooms, or even outside.

It is estimated that every day three dalit women are raped; dalit women are often forced to sit at the back of their school classrooms, or even outside; on average every hour two dalit houses are burnt down; every 18 minutes a crime is committed against a Dalit; each day two Dalits are murdered; 11 Dalits are beaten; many are impoverished; some half of Dalit children are under-nourished; 12% die before their fifth birthday; 56 per cent of dalit children under the age of four are malnourished; their infant mortality rate is close to 10 %; vast numbers are uneducated or illiterate; and 45% cannot read or write; in one recent year alone, 25,455 crimes were committed against dalits, although many more went unreported, let alone investigated or prosecuted; 70 per cent are denied the right to worship in local temples; 60 million dalits are used as forced labourers, often reduced to carrying out menial and degrading forms of work;

Segregated and oppressed, the dalits are frequently the victims of violent crime. In one case, 23 dalit agricultural workers, including women and children, were murdered by the private army of high-caste landlords. What was their crime? It was listening to a local political party, whose views threatened the landlords’ hold on local dalits as cheap labour. The list of atrocities and violence is exponential.

India is the world’s largest democracy—home to one-sixth of the world’s population. It can be proud of its many fine achievements. Like all our democracies, it is a work in progress, and there are many bright spots. India produced one of the first female Heads of Government; a dalit, Dr.Ambedkar, wrote the constitution; a female dalit became a powerful politician; a Muslim has been head of state four times; and a Jew and a Sikh are two of India’s greatest war heroes. So an astounding amount has been achieved.

However, India cannot be proud of the more general fate of the dalits, the caste system, or the extremism which feeds off ostracism and alienation and which threatens modern India.

Although Dr. Ambedkar was able to have India’s Constitution and the laws framed to end untouchability, for millions and millions of people, many of those provisions have not been worth the paper on which they are written.

Ambdekar’s own struggle may now be history; caste is not. In our generation it is surely time to make caste history.