Remarks made by David Alton at the launch of the “Merseyisde at War” commemoration of World War One Poetry – hosted by Liverpool John Moores University on November 30th 2013 in Liverpool

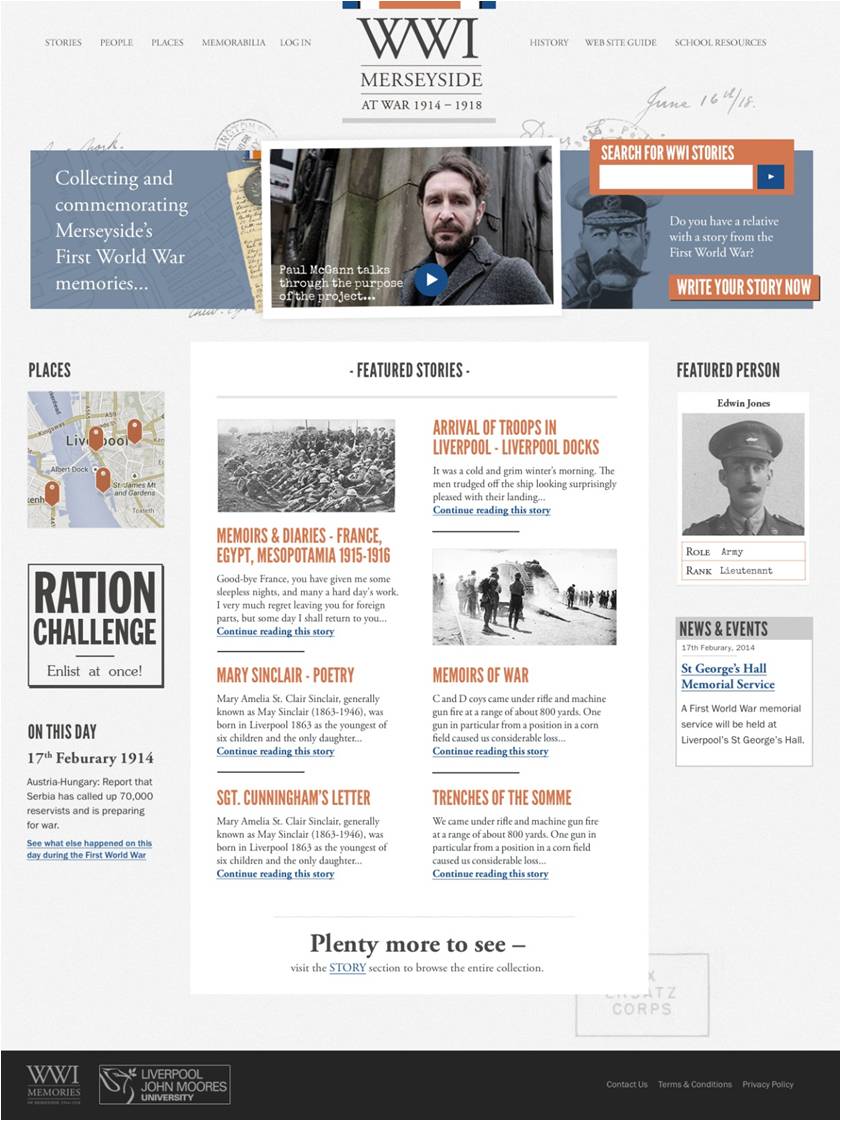

Visit: http://www.merseyside-at-war.org/

Forthcoming Roscoe Lecture:

Thursday 13 November, 2014 2pm Bill Sergeant & Tony Wainwright “Two Stories of Heroism – Chavasse and the Liverpool PALS” Tickets from Mrs.Barbara Mace: [email protected]

The commemoration of World War One poetry was organised by Professor Frank McDonough of Liverpool John Moores University

Every year in the month of November at cenotaphs up and down the land we say the words “We will remember them.” In this coming year we will remember the beginning of a war which has come to epitomise carnage and human sacrifice on a previously unimaginable scale. The war claimed more than16.5 million deaths, lives, both military and civilian. One and a quarter million of those who died originated from the United Kingdom and from what was then the British Empire. 230,000 deaths were among military personnel from countries now within the Commonwealth.

Whist the conflict raged it was decided to build the Imperial War Museum and when it opened in 1920, Sir Alfred Mond, the financier and politician, described it as, “not a monument of military glory, but a record of toil and sacrifice”.

Beyond the national commemoration of toil and sacrifice, many will recall the personal stories which have been passed down by relatives who participated in that conflict. It was called a war to end all wars but at its culmination it was acerbically remarked that the hobbled peace agreement would be a peace to end all peace. And twenty years later, so it proved.

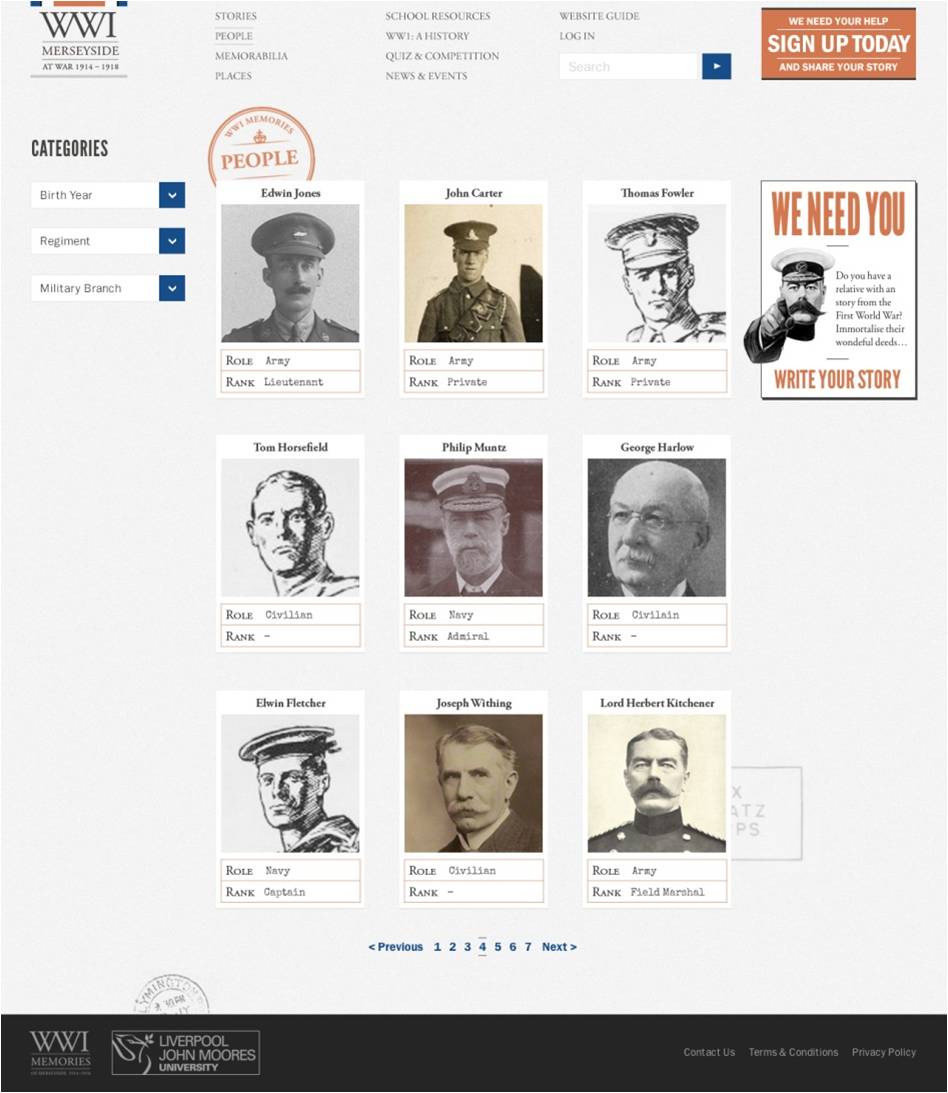

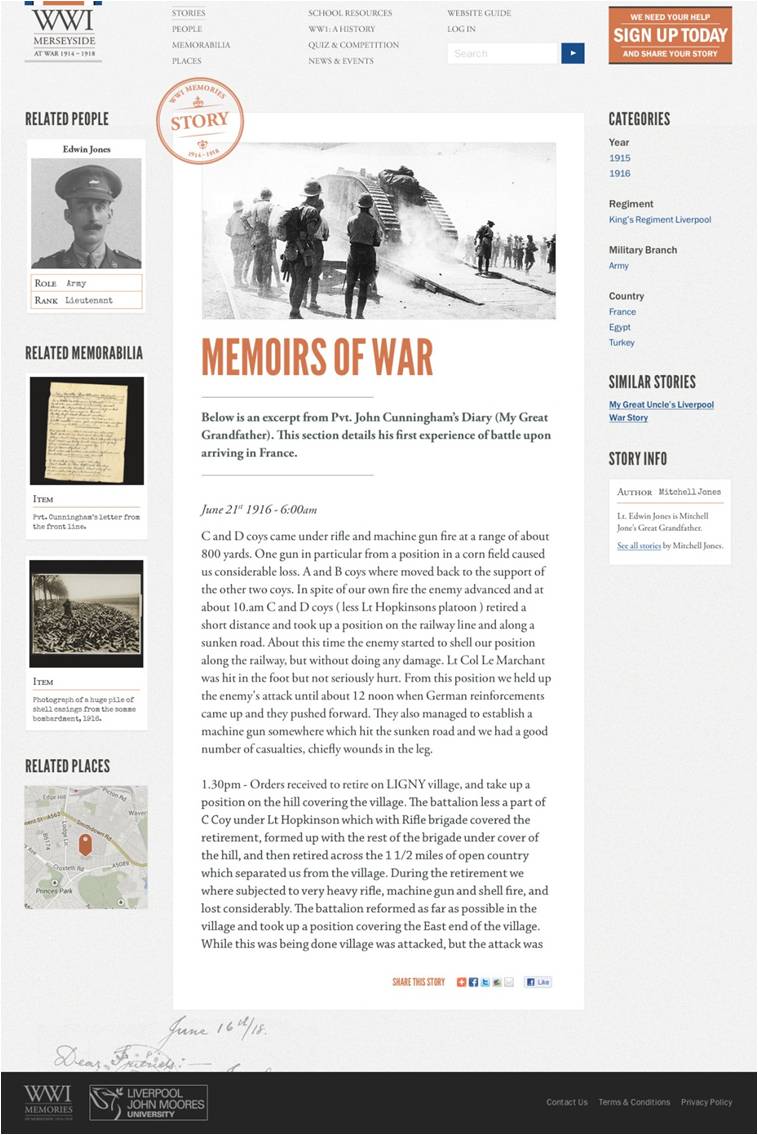

As I child my grandfather gave me photographs which he had taken or collected during his own service – which saw him in action in Allenby’s army in the Middle East. Photographs of murdered Armenians, executed in Jerusalem by the retreating armies, still have a chilling effect on me. When I took my daughter to the genocide museum in Armenia I reminded her that the world’s indifference to the plight of the Armenians would lead Hitler to scornfully remark “Who now remembers the Armenians?”.

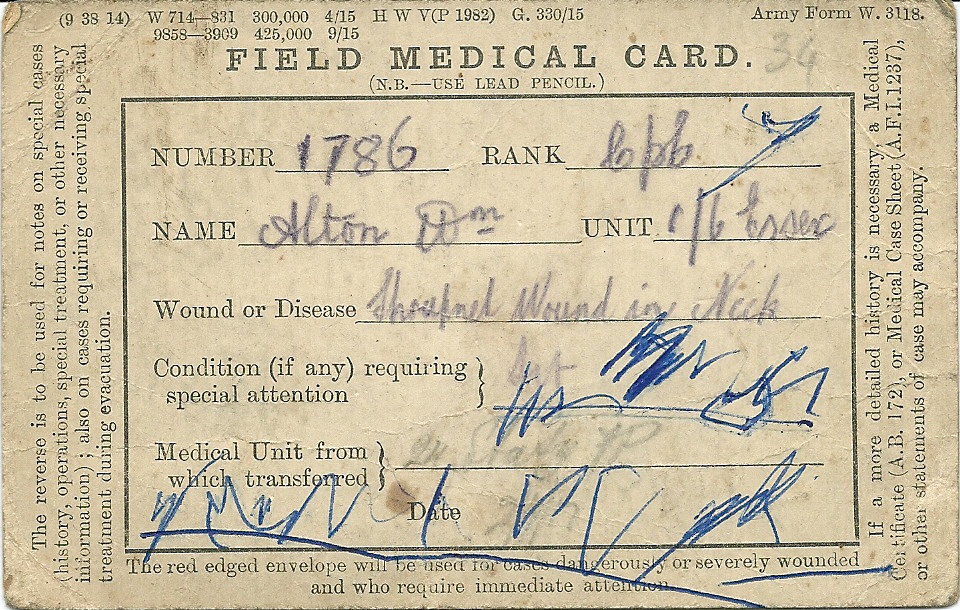

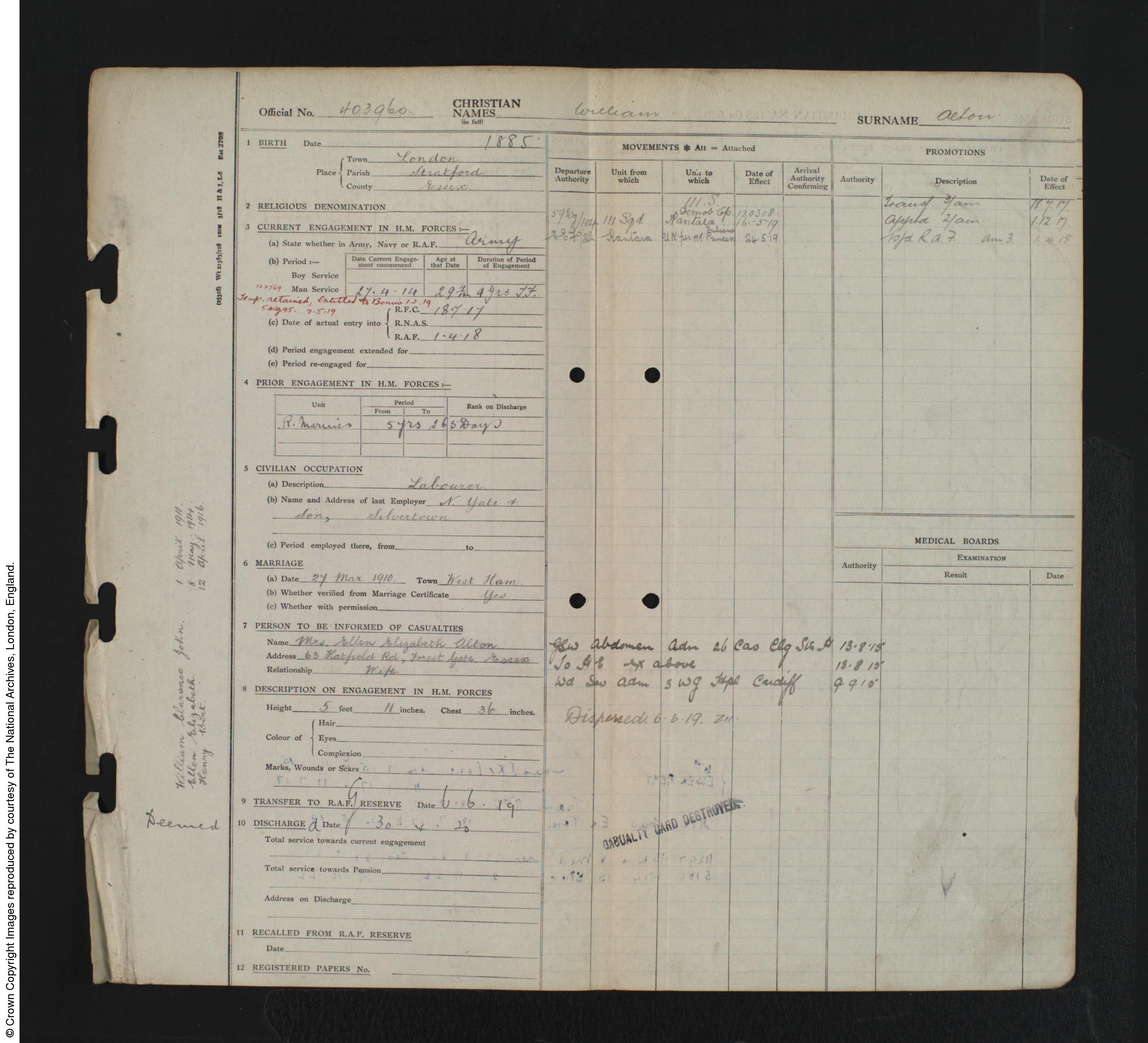

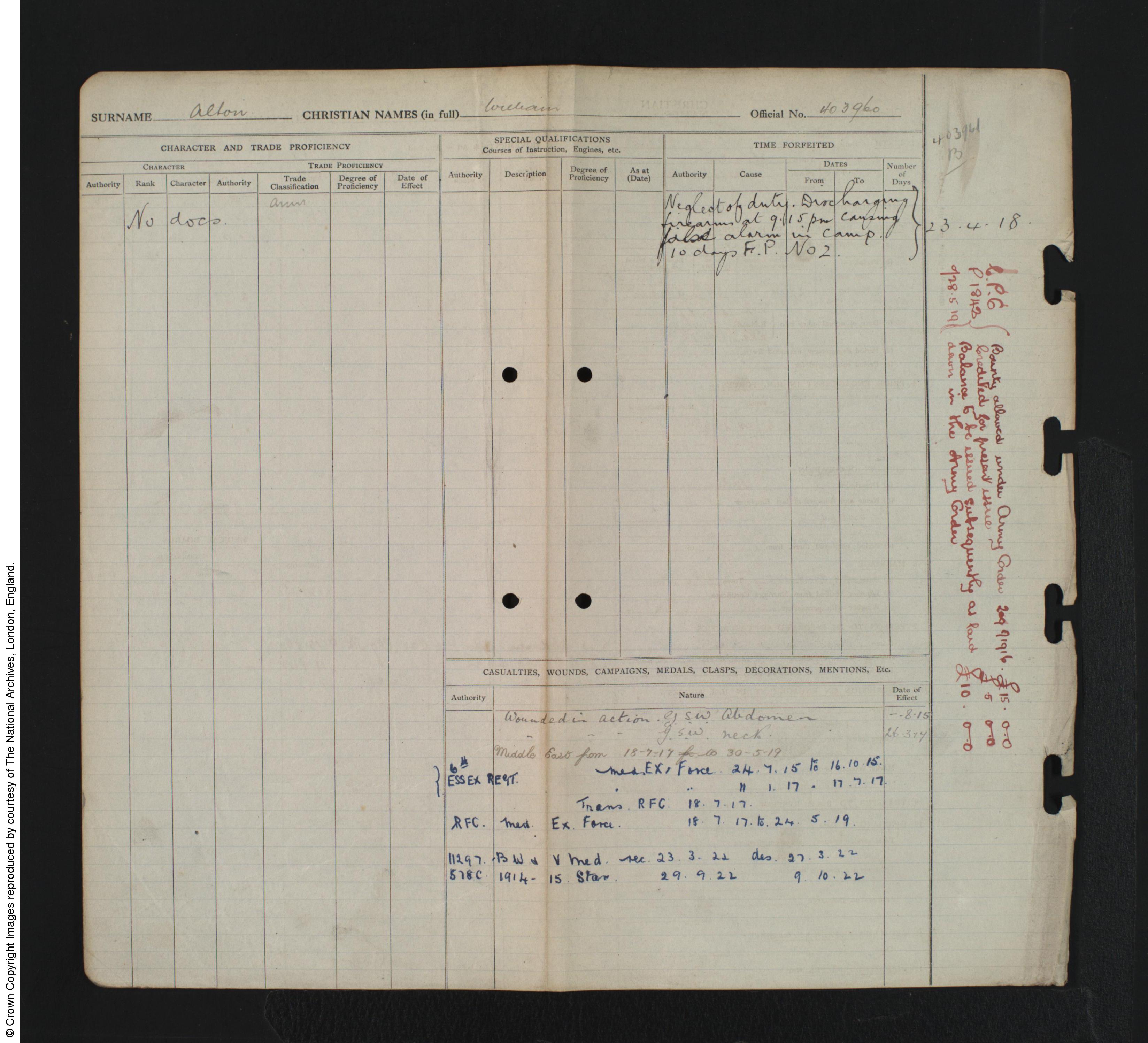

1915 Sussex Regiment – marching into Jerusalem William Alton a the Garden of Gethsemane on the right and Armenians who had been hung in Jerusalem by the retreating Turks as spies.

1915- World War One William Alton-in Egypt-with a captured German gun at Ramalah – and bathing in the River Jordan

We should always remember; and when we can bring ourselves to forgive we should never ever forget.

Our memories of the Great War inevitably focus less on the events in Jerusalem, Mesopotamia, or Gallipoli and more on the trenches of Ypres and the Somme. For here was mechanised warfare on a scale previously unimaginable.

This was a war that saw millions go to their deaths – and which divided families and communities, churches and political parties.

Think for a moment of the conscientious objectors who opposed the war both on religious and political grounds. Many of them ended up in prison. Courage came in many kinds of clothes.

It was Alan Clarke who coined the phrase “lions led by donkeys”, to describe some of those who led the British Forces.

Accounts of hampers from Fortnum & Mason and 200 British generals driving their Rolls Royces behind the lines stand in stark contrast to the putrid stench of gas in the Flanders trenches – open graves which witnessed extraordinary bravery, courage, valour and suffering as more than 1.2 million allied servicemen lost their lives: 200,000 on one day alone at the Somme. Over 2 million Germans would also die.

In Westminster Abbey lies the tomb of the unknown soldier. He is there in memory of 100,000 men whose bodies are still unaccounted for at Passchendale and all those who have died on foreign fields in graves unknown and unmarked. The remains of several unknown soldiers were taken to a private room where a blindfolded officer chose the body to represent all those who had fallen but were unidentified. An estimated 1,250,000 people visited Westminster Abbey to see the grave in only the first week.

When David Cameron launched the Government’s commemoration, he reminded us that in only 50 of the 14,000 parishes in England and Wales, were no deaths of parishioners recorded. Not a single parish in Scotland or Northern Ireland remained unscathed.

The Prime Minister identified 2014 as a moment “to honour those who served; to remember those who died; and to ensure that the lessons learned live with us”.

The twentieth century saw two wars which led to a calamitous loss of life. I doubt whether we have learned those lessons and in every generation we need to reflect on the failure which war represents. But there are other lessons for us to ponder during these commemorations.

The human spirit was assaulted but not crushed. Human endeavour matched the devastation and significant social and political change came in its wake. Patriotism, which was based on blind allegiance and acceptance of rigid social structures was replaced by a patriotism that yearned for a just and fairer society.

The First World War dramatically changed Britain’s social structures. During the war an immense contribution was made by around 1.5 million women in the workplace, not least the munitions factories, but they also ran government departments, public transport, post offices, and countless other jobs, paving the way for women’s emancipation in 1918.

Dame Millicent Garrett Fawcett put it like this:

“The war revolutionised the industrial position of women … It not only opened opportunities of employment in a number of skilled trades but, more important even than this, it revolutionised men’s minds and their conception of the sort of work of which the ordinary everyday woman was capable”.

The War also saw a phenomenal contribution by countries inextricably linked to Britain through its Empire. More than 1.5 million people from the Indian subcontinent alone served with 70,000 fatalities. More than 9,000 Indian troops were decorated for gallantry, including 11 Victoria Crosses. More than 200,000 Irishmen voluntarily enlisted, and 30.000 perished.

The Supreme Allied Commander, Marshall Foch, would remark: “I saw Irishmen of the North and the South forget their age-long differences, and fight side by side, giving their lives freely for the common cause”. And it was a War which saw whole communities unite in sacrifice and grief .

Think of the Lancashire towns which produced the Pals who would all lose their lives . In Scotland alone, 26% of the men who enlisted never returned home.

Noel Chavasse, son of the Bishop of Liverpool, was a courageous doctor who was the double recipient of the Victoria Cross

Think, too, of the courage of the non-combatants. Captain Noel Chavasse was the son of the Bishop of Liverpool. In 1915 he was awarded the Military Cross and in 1916 his first Victoria Cross. As a doctor he went into no-man’s land to tend the wounded. The following day, ignoring shrapnel injuries, he brought back twenty men whose lives he had saved. A year later, at Passchendaele, after carrying out a similar courageous act, he received shrapnel injuries to his abdomen and crawled back to the trenches, dying of his wounds; receiving a second VC for his selfless bravery.

The horror of those events is captured in Erich Maria Remarque’s novel All Quiet on the Western Front – a story which originated on the other side of the trenches but tell the same story of brutality and pain, or fear and terror, of a lost generation. Listen to these quotations from that remarkable book:

“I am young, I am twenty years old; yet I know nothing of life but despair, death, fear, and fatuous superficiality cast over an abyss of sorrow. I see how peoples are set against one another, and in silence, unknowingly, foolishly, obediently, innocently slay one another.”

“But now, for the first time, I see you are a man like me. I thought of your hand-grenades, of your bayonet, of your rifle; now I see your wife and your face and our fellowship. Forgive me, comrade. We always see it too late. Why do they never tell us that you are poor devils like us, that your mothers are just as anxious as ours, and that we have the same fear of death, and the same dying and the same agony–Forgive me, comrade; how could you be my enemy?”

“It is very queer that the unhappiness of the world is so often brought on by small men.”

“We are not youth any longer. We don’t want to take the world by storm. We are fleeing. We fly from ourselves. From our life. We were eighteen and had begun to love life and the world; and we had to shoot it to pieces. The first bomb, the first explosion, burst in our hearts. We are cut off from activity, from striving, from progress. We believe in such things no longer, we believe in the war.”

“This book is to be neither an accusation nor a confession, and least of all an adventure, for death is not an adventure to those who stand face to face with it. It will try simply to tell of a generation of men who, even though they may have escaped shells, were destroyed by the war.”

On the British side of the trenches our own writers were coming to the same conclusions.

Today we should especially recall the work of Wilfred Owen who is regarded by many historians as the leading poet of the First World War. His war poetry records the horrors of trench and gas warfare.

Born on 18 March 1893, the eldest of four children, at Plas Wilmot, a house in Weston Lane, near Oswesty in Shropshire, he was of mixed English and Welsh ancestry.

After the death of his grandfather, Edward Shaw, in January 1897, and the sale of their family home the family lodged in back streets of Birkenhead while his father temporarily worked there for the railway company employing him.

In 1898, Thomas became stationmaster at Woodside Station and the family lived with him, at three successive homes in the Tranmere district, before moving back to Shrewsbury in 1907.

Wilfred was educated at the Birkenhead Institute and at Shrewsbury Technical School.

He discovered his poetic vocation in 1903 or 1904 during a holiday spent in Cheshire.

When war broke out, he did enlist immediately – and as he was living on the Continent he even considered joining the French army – but eventually returned to England. On 4 June 1916 he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Manchester Regiment.

Once at the Front he quickly saw action and after falling into a shell hole, suffered concussion. He was blown high into the air by a trench mortar, and spent several days lying out on an embankment in Savy Wood, believed he was lying amidst the remains of a fellow officer.

Soon afterwards, Owen was diagnosed as suffering from neurasthenia or shell shock and sent for treatment to Edinbugh’s Craiglockhart War Hospital. It was while recuperating at Craiglockhart that he met fellow poet Siegfried Sassoon, an encounter that was to transform Owen’s life.

Owen asked for Sassoon’s assistance in refining his poems’ rough drafts. It was Sassoon who named the start of the famous short poem, Anthem for Doomed Youth, “anthem”, and who also substituted “doomed” for “dead”; and added the famous epiphet of “patient minds”. The amended manuscript copy, which is in both men’s handwriting, is still extant and may be viewed at the Wilfred Owen Manuscript Archive

In 14 short lines, in “Anthem for Doomed Youth” Wilfred Owen takes us deep into the horror of the war…

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle

Can patter out3 their hasty orisons.4

No mockeries5 now for them; no prayers nor bells;

Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs, –

The shrill, demented6 choirs of wailing shells;

And bugles7 calling for them from sad shires.8

What candles9 may be held to speed them all?

Not in the hands of boys but in their eyes

Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes.

The pallor10 of girls’ brows shall be their pall;

Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds,

And each slow dusk11 a drawing-down of blinds.

At the very end of August 1918, Owen returned to the front and on 1 October 1918 he led units of the Second Manchesters to storm a number of enemy strong points near the village of Joncourt.

However, only one week before the end of the war, whilst attempting to traverse the Sambre canal, he was shot and killed. The news of his death, on 4 November 1918, arrived at his parents’ house in Shrewsbury on Armistice Day. For his courage and leadership in the Joncourt action, he was awarded the Military Cross. His poetry continues to challenge and to stand as a rebuke. Most memorably, at the conclusion of today’s readings of poetry we will hear his “Dulce et Decorum Est.”

Why are we having these readings? Why have we launched a living archive to record the memories of families whose loved ones went to war? It is simply that we owe it to that generation never to forget and to pledge ourselves anew in our own times and in our own generation to do all we can to avert the carnage and brutality – the ultimate failure which war always represents. Although, one day, we may be called upon to defend our liberties and our values, the events we will commemorate in 2014 should surely instil into us a deep and renewed commitment to work unstintingly for peaceful and rational solutions to man-made challenges and problems.

Liverpool John Moores University are launching a web site to enable Merseyside people to record their own stories and those of their community and to upload photographs and letters from the Great War.