Two Remarkable Korean men – Stephen Kim and Kim Dae-jung

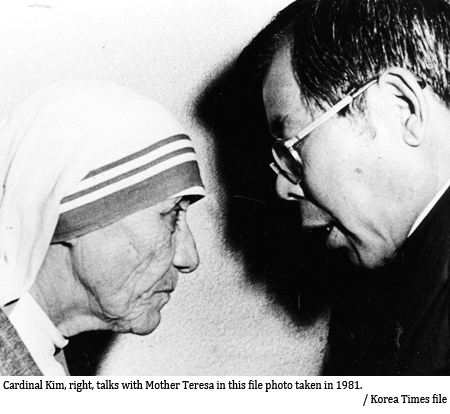

Two Remarkable Korean men – Stephen Kim and Kim Dae-jungIt is now three years since the death of South Korea’s Cardinal, Stephen Kim Sou Hwan – one of the great churchmen of the twentieth century.

At the time of his death his friend and ally, the former President, Kim Dae-jung, a Catholic convert and renowned dissident, said that Cardinal Stephen Kim had been a voice in the wilderness “for our people groaning under dictatorship”.

Born in 1922 in Daegu, in central South Korea, Stephen Kim came from an impoverished family, which often went short of rice. He was one of eight children. His father, Joseph, died while Stephen was in first grade in elementary school. His mother, Martina Seo Jung-ha, then raised the family by herself, while selling pottery and drapery to meet their needs. She instilled a profound love of their faith, telling Stephen he was destined for the priesthood.

The scion of a family which had produced one of Korea’s 8,000 nineteenth century Catholic martyrs, Stephen’s grandfather, John Kim Bo-hyeon, had died while preaching in prison after being persecuted for being a Catholic.

Despite the confidence which his mother, and later the Church had in Stephen, he sometimes questioned his own calling as well as his holiness. Refreshingly, he admitted:

“Even after becoming a priest I envied the happy married life of ordinary people, when all the family would gather for dinner.”

Fearful of forgetting his origins, he said: “My dream to live with the poor couldn’t be realised, not because of my post as Cardinal but because of my lack of courage.

“I myself come from a poor family but I forgot this and spoiled myself with luxurious habits under the pretext of performing my job. As such I must lack love for the poor. I must lack generosity, patience and humbleness. I am a sinner of all sinners.”

It was not a judgement which his countrymen shared.

Stephen’s attitudes were shaped by experience. Required at school to respond to the question “Write your impressions on being a citizen of the Japanese empire” his straightforward response was, “I am not Japanese so I have nothing to write.”

Reprimanded for this insubordination he was sent to Tokyo where, as the War in the Pacific intensified, he was rounded up by the Japanese and forced into the Japanese Imperial Army.

With a group of Korean compatriots he attempted escape. They were caught and Kim was so marked by the experience it would be many years before he would even feel able to use Japanese products or services.

In 1964 he was appointed editor of the Korean national Catholic newspaper; in 1966 named first bishop of Masan; in 1968 Archbishop of Seoul; and, in 1969, Pope Paul VI named him Cardinal. He made history, becoming the first South Korean Cardinal and also the youngest ever, ultimately becoming the longest-serving. On receiving the news of his appointment: “All I could say was: ‘Impossible!’”

In October 1978 he helped elect John Paul II. Like the new Polish Pope, Cardinal Kim would also become known as a courageous and outspoken advocate of democracy and as an opponent of military rule.

What Stephen Kim called the “long, dark tunnel” of military dictatorship, led to torture, kidnapping and imprisonment of the regime’s critics – many of whom were students. He denounced the dictators from the pulpit and to their faces.

In June 1987,during the presidency of Chun Doo Hwan, and with Kim Dae Jung under house arrest, one of many stand-offs with the military took place at Myeongdong Cathedral. This iconic site was where Korea’s first house church had been situated. It is the birth place of Korean Christianity and is the sepulchre for the remains of some of the most celebrated of the Korean Catholic martyrs. It was where dissidents, labour leaders, student activists and migrant workers would gather; a refuge providing hope for the destitute and powerless.

Cardinal Kim was ordered to hand over pro-democracy students, taking refuge in the Cathedral. He responded in trenchant terms: “If the police break into the cathedral, I will be in the very front. Behind me, there will be reverends and nuns. After we are wrestled down, there will be students.”

This grandson of a man who had died for his beliefs fully understood the gravity of the moment, later recalling: “I thought that allowing police to enter the cathedral compound to take away students was the critical juncture that would decide whether Korea went along the path to democracy or extended military regimes.”

It proved to be a turning point and the government removed the police.

“I stood, unintended, at the centre of human rights and social justice… it was an era of oppression, a dark era. We had no other choice but to wait for the truth to free us. How could a priest, as a delegate of Christ, remain silent at such a time?”

Ro Kil-myung, a Korean academic at Korea University said the Cardinal awakened the nation’s conscience: “He awakened the values of human rights and social justice, guiding the nation towards democratization. His actions were rather based on the spirit of Catholicism.”

Although banned from North Korea, Cardinal Kim remained devoted to North Koreans, and in 1995 he established a religious organization to prepare for the reunification of the two Koreas and to prepare the for re-evangelisation of the North. He inaugurated the first ‘reconciliation mass’ – a Tuesday evening service which continues to this day, each week, at the Myeongdong Cathedral

After his death in 2009 around 400,000 mourners of all faiths filed past his coffin. He stipulated that his organs should be given to others after his death – his eyes being used in two successful cornea transplants.

Cardinal Stephen Kim’s belief in sacrificial service was summed up in his last message to the Korean people. It emphasised the need for love, peace and reconciliation concluding with the words: “Thank you for the abundant love I received. Love one another

————————————————————————————–

Ban Ki Moon, the United Nations’ Secretary General, described Cardinal Stephen Kim, as “the conscience of an era” while his friend and ally, the former President, Kim Dae-jung, said, the Cardinal’s voice had been raised “for our people groaning under dictatorship”.

These two Kims, who both died in 2009, were a formidable partnership.

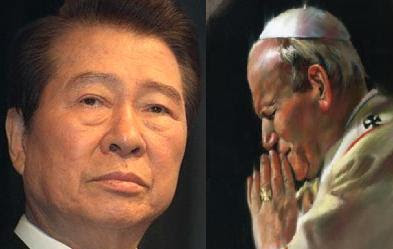

Kim Dae Jung, a Catholic convert, served six years in the prisons of South Korea’s military dictators before being elected at his fourth attempt, in 1998, as President. Two years later he received the Nobel Peace Prize, frequently being compared with Nelson Mandela and Lech Walesa.

His collection of essays, “An Endless Road: Politics and my Life”, describe how, as a boy, during Japanese occupation, Korean language and names were outlawed. He was radicalised when, during a visit by his father to his school, he was ordered not speak to his father in his native tongue.

He also had firsthand experience of Communism.

In June 1950, in Seoul when the North’s troops captured the city, he was walking to a Catholic church when three North Korean soldiers and a lynch mob of fellow travellers grabbed a young man and demanded his execution. Watching as they dragged him away Kim said “This event helped me have form anti-communism. I felt he dangers of communism more directly than by reading 1000 books about anti-communism.”

In 1956, under the influence of Chang Myun, Kim became a Catholic. Chang Myun, a Catholic leader of the Democratic Party (Minju-dang) had survived an assassination attempt. He came to share Chang’s politics and faith and Chang become Kim’s baptismal Godfather, taking as his Christian name the name of Thomas More.

Perhaps More’s influence was at work in Kim’s essays when he asserts: “I decided I should become a politician who would not spare his life at the cost of a proper faith.”

In the 1970s Kim Dae Jung’s increasingly high political profile forced him to leave the country. In 1973, in exile in Japan, he was almost left for dead after criticising President Park for establishing himself as a virtual dictator. Agents, believed to be from South Korea’s National Intelligence Agency, kidnapped Kim from his Tokyo hotel.

In his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech he said: “The agents took me to their boat at anchor along the seashore. They tied me up, blinded me, and stuffed my mouth. Just when they were about to throw me overboard, Jesus Christ appeared before me with such clarity. I clung to him and begged him to save me. At that very moment, an airplane came down from the sky to rescue me from the moment of death.”

He added: “I have lived, and continue to live, in the belief that God is always with me. I know this from experience.”

On return from exile his home, in Mapo, Kim became a virtual prison, his wife describing it as “a truly Orwellian world of illegal brutality.”

Arrested again in 1980, this time he was sentenced to death.

The following week John Paul II intervened and Kim’s sentence was commuted to 20 years in prison.

During Kim’s court appearances – bracketed by military policemen – he was handcuffed and forced to appear in prisoners’ uniform. Describing how he was held in an underground cell, denied a lawyer, and interrogated each day for 15 hours, he said: “The intention was to make me go insane. I could hear someone moaning in a room next to me. I was stripped naked and forced to wear worn-out military fatigues. I was threatened with torture.”

The Kim Dae Jung Library in Seoul holds some of the books he read in prison along with his letters, blue prison uniform, his Bible, rosary and cross.

His prison letters and those of his wife, Lee Hee-Ho, a devout Methodist – who wrote to him almost daily – are deeply moving.

Full of references to his Catholic faith, prayer, scripture, Jesus and God, he reiterated that his opposition to the regime rested on his religious beliefs.

In response, Lee Hee-Ho records her encouragement to her husband: “a day for you must feel like a thousand years” and she tells how she weeps “while singing hymns at church. I can see Jesus Christ carrying the heavy cross all alone up to Golgotha.” describing Jesus as “the hero of absolute solitude.”

In July of 1981, 24 years after his baptism, she reminds Kim that “Today marks the meaningful anniversary if your decision to believe in God your saviour. I hope and believe that Our Lord will remember this day as the great moment of your life when you were marked by your promise to serve and follow Him and that he will bestow on you His renewed blessing.”

Her final letter recorded her belief that “with faith our prayers will come true” and that they should renew their prayer that “God will not turn away from us.”

In 1982 Lee’s prayers were answered and Kim went to America, teaching at Harvard, but continuing to campaign for political change, returning to Seoul in 1985.

In 1997 Kim Dae Jung contested the South Korean presidency for the fourth time. In a climate of economic collapse and a split opposition, Kim secured 40% of the vote – Korea’s first peaceful transfer of power from a government party to the opposition. On February 25th, 1998, he was sworn in as President, serving out a full term of office until 2002.

Kim is credited with guiding Korea out of an economic quagmire, of developing welfare provision, ushering in transparency, turning South Korea into a world player, further entrenching democracy and, through his Sunshine Policy, seeking new ways to promote peace and reconciliation.

His entire life was dedicated to the promotion of democratic values and in the service of Korean people. It’s a story which North Korea’s Kim Jong Un – and whoever becomes South Korea’s next President should study with care.