Shahbaz Bhatti – one year on since his brutal assassination: what to make of his sacrificial life and the treatment of minorities in Pakistan

Feb 22, 2012 | News

The First Anniversary of the Death of Shahbaz Bhatti

David Alton

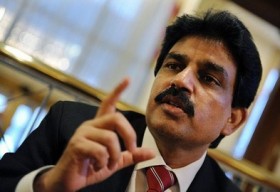

On March 2nd, 2011, aged 42, Clement Shahbaz Bhatti, Pakistan’s Federal Minister for Minorities, was brutally murdered. His assassination not only robbed Pakistan’s National Assembly of a dedicated, honest, and able politician but his death also threw into sharp relief the plight of Pakistan’s minorities, whose fearless champion he had become.

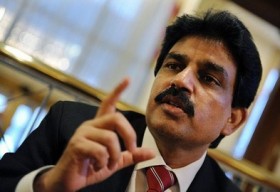

Shahbaz Bhatti - Pakistan's outstanding Minister for Minorities murdered one year ago.Mohammed Ali Jinnah - Pakistan's enlightened founding father who insisted that minorities should be given respect and protection in the new country.

On this, the first anniversary of his killing – and after the detention, this week, in Dubai of a possible suspect involved in the murder – it is worth reflecting on the life of this singularly virtuous man while considering the continuing suffering of the people on whose behalf he sacrificed his life.

One of five children, Bhatti was born in 1968 in Lahore to Catholic parents. They originated from a village near Faisalabad. His father, Jacob, after army service, became a teacher and then chairman of the board of the churches in Khushpur. The family were observant Catholics whose faith was central to their identity and lives.

Unsurprisingly, as he was growing up, Bhatti became acutely aware of what it was like to stand out as different.

In a population of over 172 million people, only about 1.5% (3 million) is Christians (half Catholic, half Protestant).

In part, the Catholic Church has its roots in the Irish presence within the British Army during colonial rule and the significant Goan community which the British established in Karachi.

There are other minorities: in 2011 the Pakistan Hindu Council put the number of Hindus at some 7 million people. Pakistan’s cruelly treated Ahmadiyya community is 4 million strong. There are also small numbers of Sikhs, Buddhists, Bahais and Zoroastrians – all of whom have faced relentless violence and profound discrimination. Along with those Muslims caught up in the sectarian violence between Sunni and Shi’a, the minorities have suffered grievously Terrorism and instability have led to over 35,000 deaths since 2003 and 2,522 fatalities in one recent six month period alone.

In 1947, at the time of partition, Muhammad Ali Jinnah gave a speech to the New Delhi Press Club, setting out the basis on which the new State of Pakistan was to be founded. In it, he forcefully defended the right of minorities to be protected and to have their beliefs respected:

“Minorities, to whichever community they may belong, will be safeguarded. Their religion, faith or belief will be secure. There will be no interference of any kind with their freedom of worship. They will have their protection with regard to their religion, faith, their life and their culture. They will be, in all respects, the citizens of Pakistan without any distinction of caste and creed.”

These words became a forgotten aspiration when, in 1956, Pakistan became an Islamic Republic – although, even then, the Constitution guaranteed equal citizenship to all its citizens and guaranteed freedom of religion. Notable Christians, such as Mr. Justice A.R.Cornelius became Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and others became celebrated members of the Pakistan Air Force and the professions.

But, as Bhatti was growing up a campaign of discrimination, intimidation and violence against the country’s Christian minorities had begun to disfigure the ideals of Muhammad Ali Jinnah and by the 1990s attacks had become routine. The world slowly began to wake up to the enormity of the suffering when, in 1998, Bishop John Joseph, the Catholic bishop of Faisalabad, shockingly, as a protest against the cruelty perpetrated against his flock, took his own life.

Following Bishop Joseph’s suicide, Shahbaz Bhatti founded the All Pakistan Minorities Alliance and in 2002 was unanimously elected as APMA’s chairman. In the same year he became a member of Benazir Bhutto’s Pakistan People’s Party. Although the authorities placed him on their Exit Control List his name was removed and, in 2008, he was both made a Minister and, remarkably, given Cabinet rank – the only Christian in Pakistan’s Cabinet.

At the time of his appointment, Bhatti singled out the country’s Blasphemy Law as the principal instrument which had been used to vexatiously prosecute and harass minorities. He said it should be amended and he proposed a law to ban hate speech, changes to the school curriculum, representation for minorities in government and parliament, and eight months before his death, a National Interfaith Consultation out of which the country’s religious leaders issued a declaration against terrorism.

In doing all this, he knew that his outspokenness and singularity would make him a primary target for Pakistan’s radical Islamists and sensed the almost inevitable consequence of his courageous words and actions. However, he said that his stand would “send a message of hope to the people living a life of disappointment, disillusionment and despair” adding that his life was dedicated to “the oppressed, the down-trodden and the marginalised” and to “the struggle for human equality, social justice, religious freedom and the empowerment of religious minorities’ communities.”

Perhaps the greatest tragedy of Bhatti’s murder is that his countrymen overwhelmingly share his ideals.

In a survey of Pakistan opinion, 90% cited religious extremism as the greatest threat to their country. Presumably the overwhelming majority of the UK’s 1.2 million British citizens of Pakistani descent must also contrast the tolerance of their adopted home, and the protection which minorities receive, with the truly shocking intolerance of their homeland.

That Bhatti’s life would be in danger became very clear in January 2011 when the Governor of the Punjab, Salman Taseer, was murdered for seeking clemency for a Christian woman sentenced to death under the Blasphemy Laws. One year later, in Pakistan’s climate of impunity, demonstrators gathered to shower rose petals on his assassin.

Two months after Taseer’s death Shahbaz Bhatti would follow him to the grave.

On leaving his Islamabad home he was gunned down by self described Taliban assassins. He had accurately predicted his own death – knowing that the cause he had embraced – Jinnah’s cause – would ultimately cost him his life. His murderers scattered pamphlets describing him as a “Christian infidel”. The leaflets were signed “Taliban al-Qaida Punjab.”

The Prime Minister, David Cameron, called the murder “absolutely brutal and unacceptable” but Cardinal Keith O’Brien sharply contrasted the rhetoric with the reality: “To increase aid to the Pakistan government when religious freedom is not upheld and those who speak up for religious freedom are gunned down is tantamount to an anti-Christian foreign policy.“

At the beginning of this year, Baroness Sayeeda Warsi, Chairman of the Conservative Party, visited Pakistan and in the Lords told me that “ the assassinations of Salman Taseer and Shahbaz Bhatti were tragic for both Pakistan and the rest of the world. They were a personal tragedy for me because of my personal relationship with Shahbaz Bhatti.” She made a point of visiting the Catholic Archbishop of Karachi and said that the local Christian community “is doing well, despite its challenges”. She defended British aid to Pakistan – which can end up in the hands of radicals and rarely reaches the minorities.

Christians who are not “doing well” continue to face prosecution, discrimination, forced conversions to Islam, rape, and forced marriage. This denial of civil rights and the failure to protect minorities are all directly attributable to the rise of the Taliban and the failure of the civil and security forces.

Shahbaz Bhatti was a brave advocate of reform of the country’s Blasphemy Law. But he was more than this.

His was a sacrificial and exemplary life and his life was given for the common good.

By definition, a martyr is a witness and an example to the Christian community of how to behave – and Bhatti was certainly a witness for truth and for justice. He stands in a long tradition – from Beckett to More, Kolbe to Romero – of men willing to sacrifice their lives as the price for upholding their beliefs.

After his death, in Bhatti’s diocese of Faisalabad, local Catholics fasted, prayed and processed, venerating his legacy. His bishop, Archbishop Saldanha of Lahore subsequently announced that the Pakistan Bishops Conference have written to Pope Benedict asking that Bhatti’s name be recognised as a name to be listed among the martyrs of the faith.

On the anniversary of Bhatti’s death recall the words of Pope Benedict last year: “I ask the Lord Jesus that the moving sacrifice of the life of the Pakistani minister Shahbaz Bhatti may arouse in people’s consciences the courage and commitment to defend the religious freedom of all men and, in this way, to promote their equal dignity.”

Who better, then, to now raise to the altars and, in these disturbed and dangerous times, to entrust with the cause of religious freedom – for which there is no patron saint – than Shahbaz Bhatti?

This article appeared in The Catholic Herald, February 24th 2012.

https://www.davidalton.net/2012/01/27/the-real-test-for-the-arab-spring-how-minorities-are-treated/