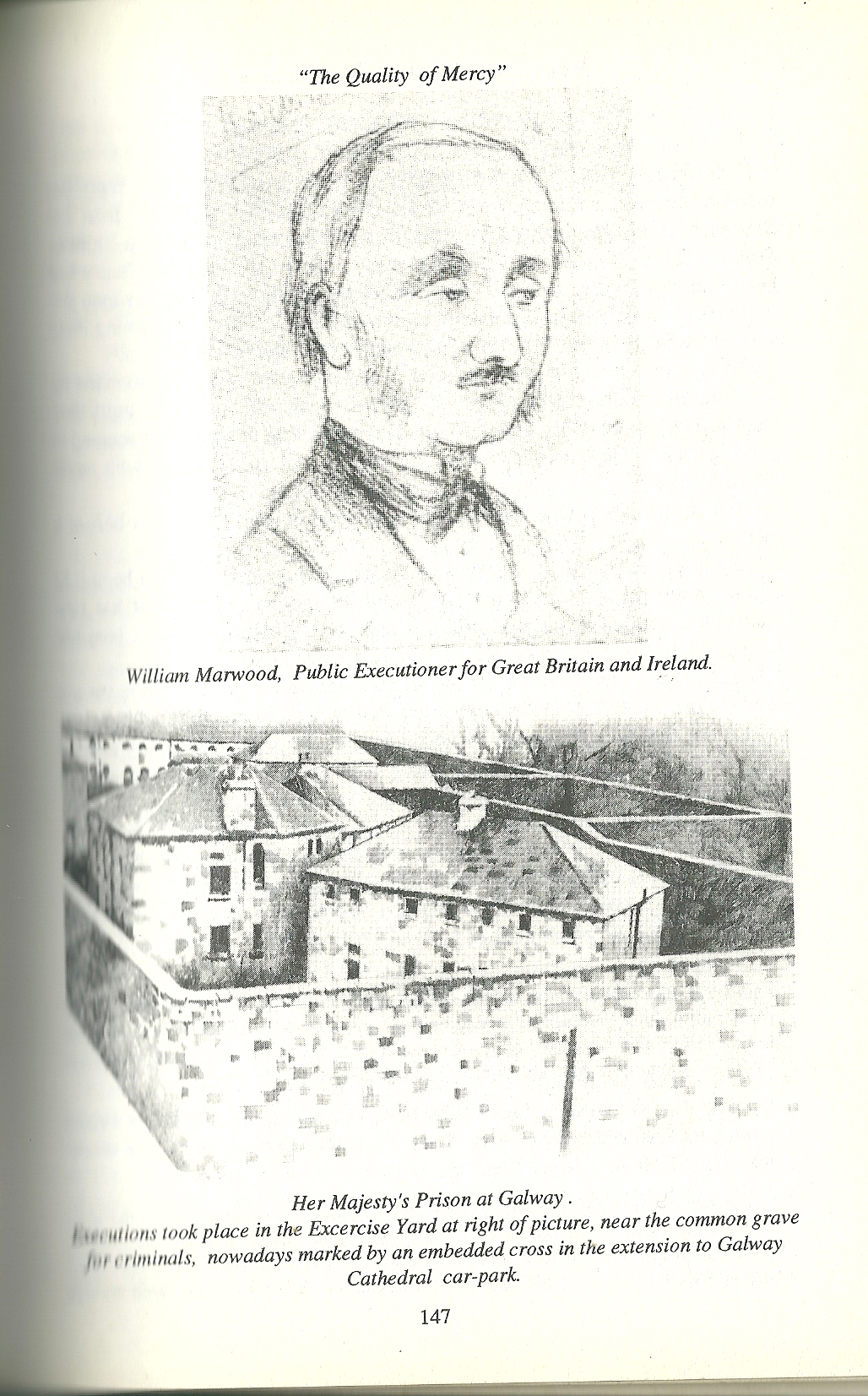

On the 15th of December 1882 whilst, poignantly, Bridget Joyce was giving birth to their daughter, her husband Myles was facing William Marwood, the Public Executioner for Great Britain and Ireland. As he was taken to his death at the gallows in Galway Prison – held guilty for the murder of the Joyces of Maamtrasna – he told a kinsman “If there’s a God in Heaven, there is no rope in Galway fit to hang me.”

Despite an affirmation by the other two condemned men insisting on Joyce’s innocence, there was to be no reprieve. A last moment despatch to George Mason, the Prison Governor from Lord Spencer, Ireland’s Viceroy, baldly stated that: “The Law must take its course.”

Having received absolution at 6.00am and attended Mass, Myles Joyce was given the last rites by the Prison Chaplain, Fr.Greaven. As the priest recited the Litany of the Saints, Myles recited his own litany: “Feicfidh me Iosa Crist ar ball beag – crochhadh Eisean san eagcoir chomh maith – I will see Jesus Christ soon – He was hanged in the wrong too.” At the scaffold, in a firm voice, he announced again “As God is my witness I never did it. And it is a poor case to die on a platform when you are innocent. May God help my wife and her five orphans. I had no hand nor part in it, but I have my priest with me.” His dying words were “I am going before my God. I am as innocent as the child in the cradle.”

A contemporary newspaper report recorded the grisly details of his botched public execution:

“Myles Joyce continued speaking rapidly, even after Marwood had drawn the white cap over his face and fixed the noose around his neck, and was, in fact, at the moment the bolt was drawn speaking . . . The instant Marwood touched the levers the three bodies instantly disappeared.

Two of the ropes remained perfectly motionless, but the third, that by which Myles Joyce was hanged, could be seen by those who watched it closely to vibrate, and swing slightly backwards and forwards. It soon became evident, from Marwood’s behaviour, that there had been a hitch of some kind or other, and he muttered, “Bother the fellow”, sat down on the scaffold, laid hold of the rope, and moved it backwards and forwards… Joyce was not killed as rapidly as the others and that the man struggled for some time before succumbing” His body was thrown into a quicklime grave near Galway Cathedral.

T.P.O’Connor, the Irish Nationalist MP for Galway (and later for a Liverpool constituency) said “The scene will live in Irish memory to the end of time.” He said that “For months afterwards the story of Myles Joyce was on every Irish lip.”

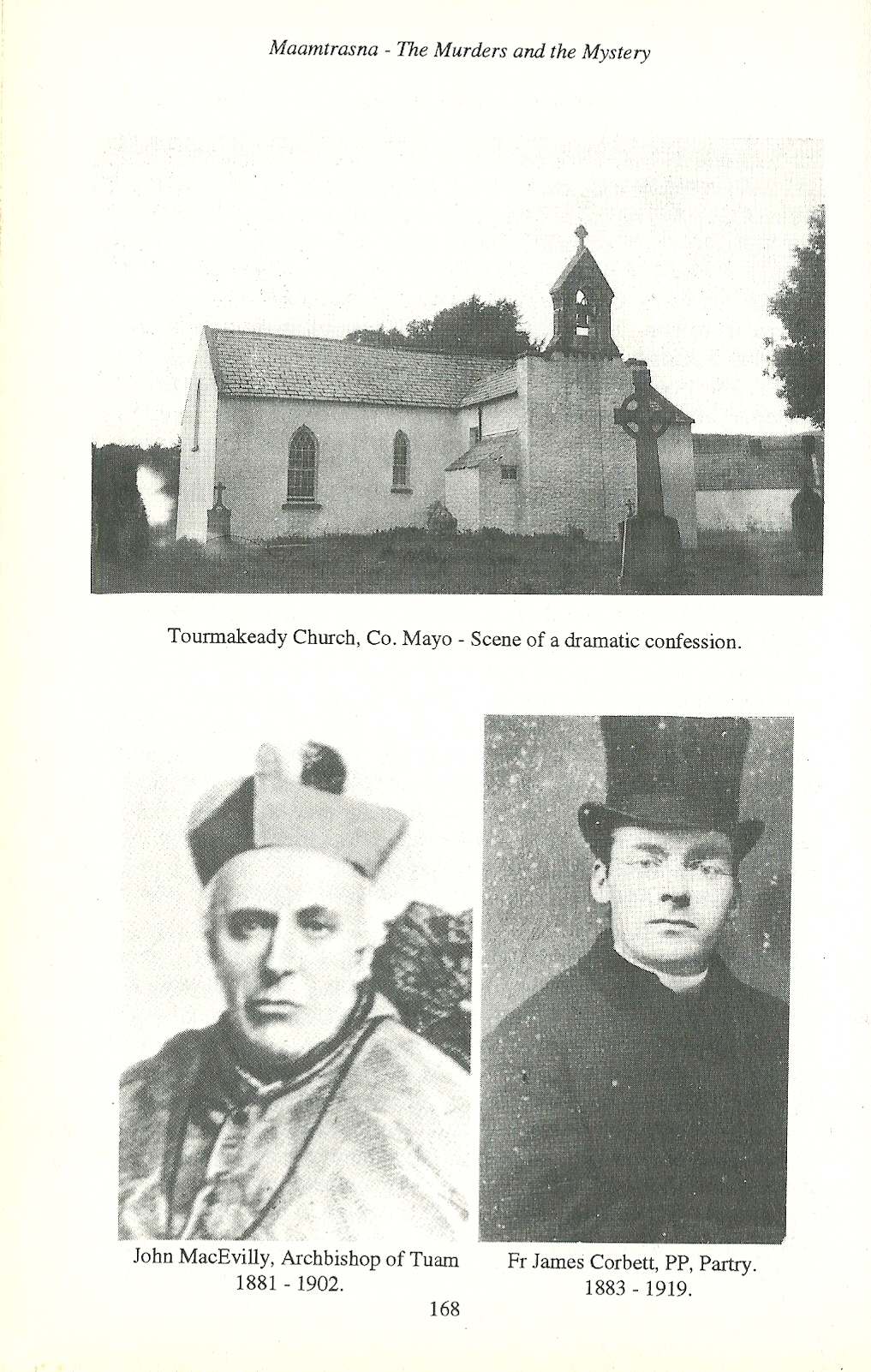

The story certainly did not die with the death of Myles Joyce. Two years later, in August 1884 Dr.John Mac Evilly, the Archbishop of Tuam, arrived in Tourmakeady to administer the Sacrament of Confirmation. Tom Casey – one of those whose evidence had taken Myles Joyce to the gallows, entered the church, and, holding a lighted candle, walked to the altar, and dramatically declared before the Dr.MacEvilly and the gathered congregation that he had brought about the death of the innocent Myles Joyce and the imprisonment of four other innocent men.

The Connaught Telegraph recorded this astonishing moment with an editorial entitled “the Law Made Murder.” Archbishop Mac Evilly wrote to Lord Spencer “in the interests of justice and civil society…and respect and confidence in the administration of law, to lay the whole case before your Excellency as it came before me.” He called for a full public inquiry. In a deliberate slight, Spencer delegated an official to reply to Dr.Mac Evilly and insisted that no inquiry was required. In a tough response, the Archbishop reminded the Viceroy that “It is hardly conceivable how, in the very jaws of death, (Myles Joyce) would allow himself to be launched into eternity with a lie on his lips.” An even lower grade civil servant sent a six line reply again stating that the cased would not be reopened.

Politicians were by now also becoming involved. Tim Harrington, the Westmeath MP, promised to raise the case in the House of Commons. In 1882, during his protests against tenant evictions, Harrington had himself been incarcerated with some of the Maamtrasna prisoners and now led a vigorous and tenacious campaign to uncover the truth. Harrington travelled to Maamtrasna and painstakingly amassed statements, checked discrepancies and conflicting evidence. He issued a formal challenge to Spencer: “Officials who would acquit themselves of the blood of the innocent will need to vindicate themselves.” Later he documented the case in a booklet.

On October 24th 1884 Harrington secured a full parliamentary debate on the Maamtrasna murders. It raged over six nights. Harrington angrily pointed to the Crimes Act which “has worked manifold injustice” and in the case of Myles Joyce “has led to the execution of an innocent man.”

Arthur O’Connor MP was the first to speak for the amendment proposing a public inquiry and said that although “It is impossible to bring back the soul of Myles Joyce; but if any respect for the law is to exist in Ireland, …legalized murder should no longer be allowed to stalk with impunity throughout the Island.” Many Irish MPs intervened, including Charles Stewart Parnell , and Harrington was given unexpected and strong support by the Conservative MP, Randolph Churchill.

The debate brought the Prime Minister, Mr. Gladstone, to the Chamber, where he defended Lord Spencer, Irish officials, and the process of law. It wasn’t his finest moment but the Whips did their duty and the Government secured 219 votes against the 48 who voted for an Inquiry. The outcome of the vote to one side, this case opened Gladstone’s eyes to the injustices in Ireland and paved the way for his support for land reform, for Irish Home Rule and his “mission to pacify Ireland.”

It would require more than a century to pass before, Fr.Jarlath Waldron, in 1992, would publish his masterly account. At the time, my friend Lord (Eric) Avebury said that his book “is a timely reminder of the fallibility of justice.”

When recently talking about the case we pointed to the parallels with more recent miscarriages of justice – the Birmingham Six, the Guildford Four – and the implications for the use of capital punishment. And we were also both agreed that even with this passage of time, the injustice committed should not be allowed to stand. The true healing of British-Irish relations requires that, wherever possible, ghosts should be laid peacefully to rest and wrongs righted.

Lord Avebury and I will ask our current Minister for Justice, Ken Clarke, to call for the Maamtrasna murder files and, once and for all, to posthumously clear the name of Myles Joyce, an innocent man executed for a crime he did not commit.

Great British Energy Bill – Lord Alton – forced labour in renewables supply chains 30.04.25

https://youtu.be/oJ14A40thm4 House of...