When the Maamtrasna murders took place in 1882, the little settlement of Maamtrasna was situated in County Galway. Here, about 250 families scratched a living from the land, labouring in the shadow of Maamtrasna Mountain. In 1898, a reconfiguration of county boundaries placed Maamtrasna in County Mayo. But no reconfiguration or reworking of boundaries would wipe away the memory of the primitive act of barbarism which occurred at this deceptively idyllic spot, just a mile from the banks of Lough Mask.

The Joyce Country lies between the Mask and Lough Corrib and takes its name from a Welsh family who settled here in the 13th century. It incorporates the communities of Maam, Corr na Mona, Clonbur, Cloghbrack, Finney, Tourmakeady, Cong, Cross and The Neale. The Joyce family motto is “Mors aut honorabilis vita – Death before dishonour.”

For the Joyce clan, 1882 would be a year of death and dishonour as Maamtrasna became the scene of one of Ireland’s most horrific murders. The deaths, on August 18th of that year, of five members of the family of John Joyce, hacked down and murdered in their own home, would reverberate throughout Britain and Ireland and be the subject of a full-scale parliamentary debate, requiring the Prime Minister’s personal intervention.

The tragedy had unfolded when John Collins, a neighbour and tenant farmer, arrived at the home of John Joyce on an errand to borrow two wool cards. He found the door pulled away and John Joyce lying dead on the floor, naked. Returning to the house with other villagers they quickly discovered three more bodies – Joyce’s aged mother-in-law, Margaret, his wife Bridget, whose skull had been crushed, and the corpse of his daughter, Peggy. Two boys were seriously wounded – Michael, aged seventeen, had been shot in the stomach and head and later died. Patsy, aged ten, would survive.

Two days after the murders The Times said that: ‘No ingenuity can exaggerate the brutal ferocity of a crime which spared neither the grey hairs of an aged woman nor the innocent child of 12 years who slept beside her. It is an outburst of unredeemed and inexplicable savagery before which one stands appalled, and oppressed with a painful sense of the failure of our vaunted civilisation.’

The Archbishop of Tuam, Dr.John Mac Evilly, said that “It is sad to think that scenes which lake, stream and towering hills have endowed with so many features of natural beauty should…. be changed into a kind of Western Golgotha, literally reddened with blood.”

The context in which these murders occurred was one of widespread violence.

The Land League had been established in Castlebar in 1879 by Michael Davitt, a former Fenian prisoner, and under the unlikely leadership of Charles Stewart Parnell (himself a Protestant landowner from Wicklow) the League challenged the excesses and cruelties of the landlords. Secret Societies had been spawned and violence was not far behind. Lord Leitrim, a West of Ireland landlord, had been executed in broad daylight; earlier in the year of the Maamtrasna murders, the bodies of two men working for Lord Ardilaun (the Guinness family who owned nearby Ashford Castle, in Cong) were dumped in Lough Mask; the agent of the hated Lord Clanricard was shot dead along with a Claremorris landlord. And the killing had become indiscriminate. In Ballinrobe, Lord Mountmorres, a progressive and compassionate landlord who never evicted his tenants was shot dead. Parnell and other leaders of the Land League s were imprisoned.

And, most famously of all, three months before Maamtrasna’s murders, Lord Frederick Cavendish, the new Irish Chief Secretary, was assassinated in Dublin, in Phoenix Park, along with Thomas Burke, the country’s most senior civil servant.

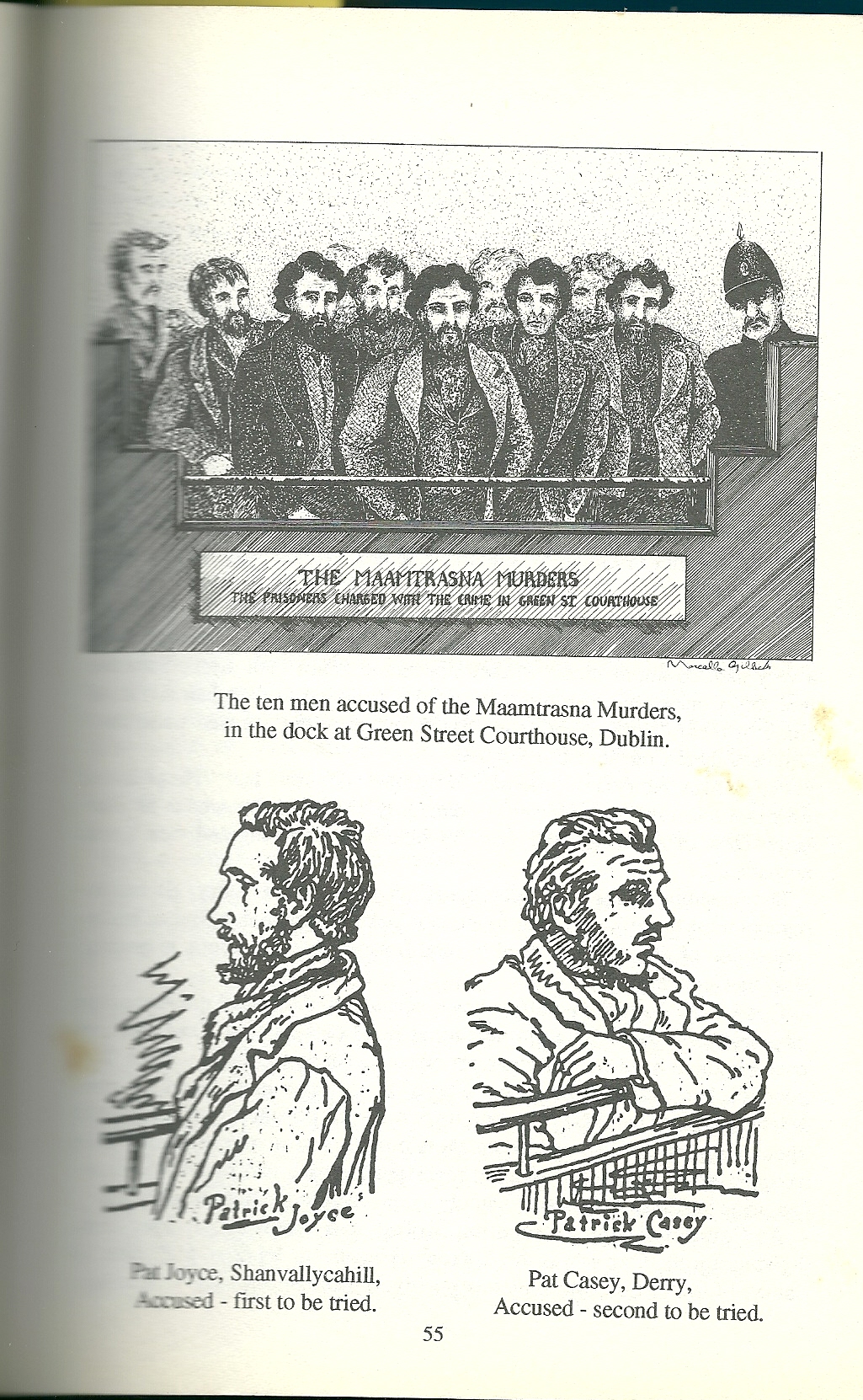

This was the context in which Anthony Joyce, who was a cousin of the murdered John Joyce, went to the police, and with two of his relatives, gave a sworn statement to the authorities that on the night of the murder they had secretly followed a crowd to the Maamtrasna homestead and had seen ten men murder John Joyce and his family. These “Malora” Joyces had their own reasons for naming Anthony Philbin, Tom Casey, Martin Joyce, Myles Joyce, Patrick Joyce, and Tom Joyce, Pat Joyce, Patrick Casey, John Casey, and Michael Casey.

More than a century later, in trying to unravel the motives of the murders and the accused, a local priest, Fr.Jarlath Waldron, in an account covering more than 300 pages, set out motives which range from blood feuds over sheep stealing to non payment of dues or betrayal of secret societies; and different motives may well have been at work among the murderers.

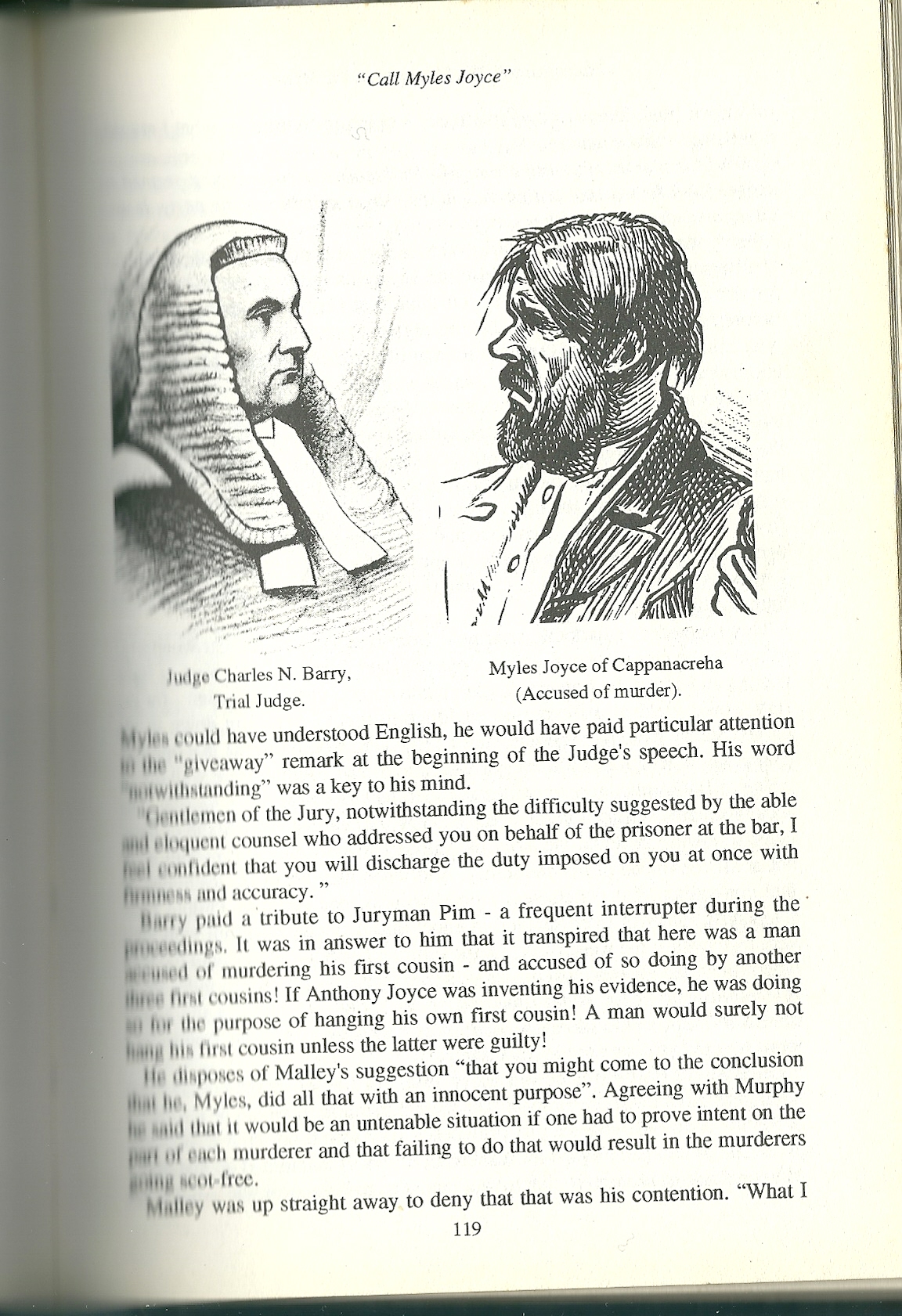

By the end of Fr.Waldron’s “Maamtrasna – the Murders and the Mystery” there is still a great deal of Irish mist covering both the motives and the identity of the perpetrators of these horrific crimes. What does become exceedingly clear, however, is that Myles Joyce, one of the three men who was subsequently executed, had no hand in the murders and that what passed for a trial was a travesty of justice. The Crown paid accusers the accusers £1,250 in blood money, a substantial sum in those straitened times, for perjured depositions and tainted evidence (Lord Spencer, the Lord Lieutenant, an ancestor of Princess Diana, said the payments were for “courageous and praiseworthy conduct in te pursuit and prosecution of the murderers”) ; later recantations were never properly considered; other declarations were never placed before the jury; the proceedings were conducted in English while the accused were Irish speakers; and verdicts were allowed to stand which would lead to penal servitude and executions. The prosecution case was a farrago of deceits and the defence was lamentable – simply going through the motions. Myles Joyce never had a chance.

As they faced the hangman’s noose at Galway Prison, one of the accused, Patrick Casey signed a declaration before the prison Governor, George Mason, that, of his own free will “as a prisoner under sentence of death….Myles Joyce is innocent in this case.”

There were repeated pleas for mercy – including a letter from his wife Bridget pleading “I publicly confess before high Heaven that he never committed the crime nor left his house that night. Will the evidence of two Informers, the perpetrators of the deed, hang an innocent man?”

She ended her letter imploring the Lord Lieutenant, Lord Spencer, to reopen “the case of an innocent man which leaves a widow and five orphans to be, before long, adrift o the world. I crave for mercy.”

But it was all to no avail. No mercy was shown and no justice done.

Next …

David Alton concludes the story of the Maamtrasna murders and how demands by MPs and an Archbishop for a public inquiry into the execution of Myles Joyce, were rejected by the Prime Minister and explains why it’s time that Britain cleared an innocent man’s name.

David Alton concludes the story of the Maamtrasna murders and how demands by MPs and an Archbishop for a public inquiry into the execution of Myles Joyce, were rejected by the Prime Minister and explains why it’s time that Britain cleared an innocent man’s name.

Questions about the number of children in Sudan who are (1) affected by malnutrition, and (2) no longer in education, due to the war; and about the percentage of UK aid to Sudan that (1) reaches recipients via emergency response rooms, and (2) supports emergency response rooms.

Lord Collins of Highbury, the Foreign,...