A Dutch Catholic writer, Koenrad De Wolf, has recently published the remarkable story of Alexander Ogorodnikov, one of the great Christian dissidents of the Soviet Union. The book has now been translated and it is to be published in English in the New Year. It is the story of a singular man and which deserves to be told.

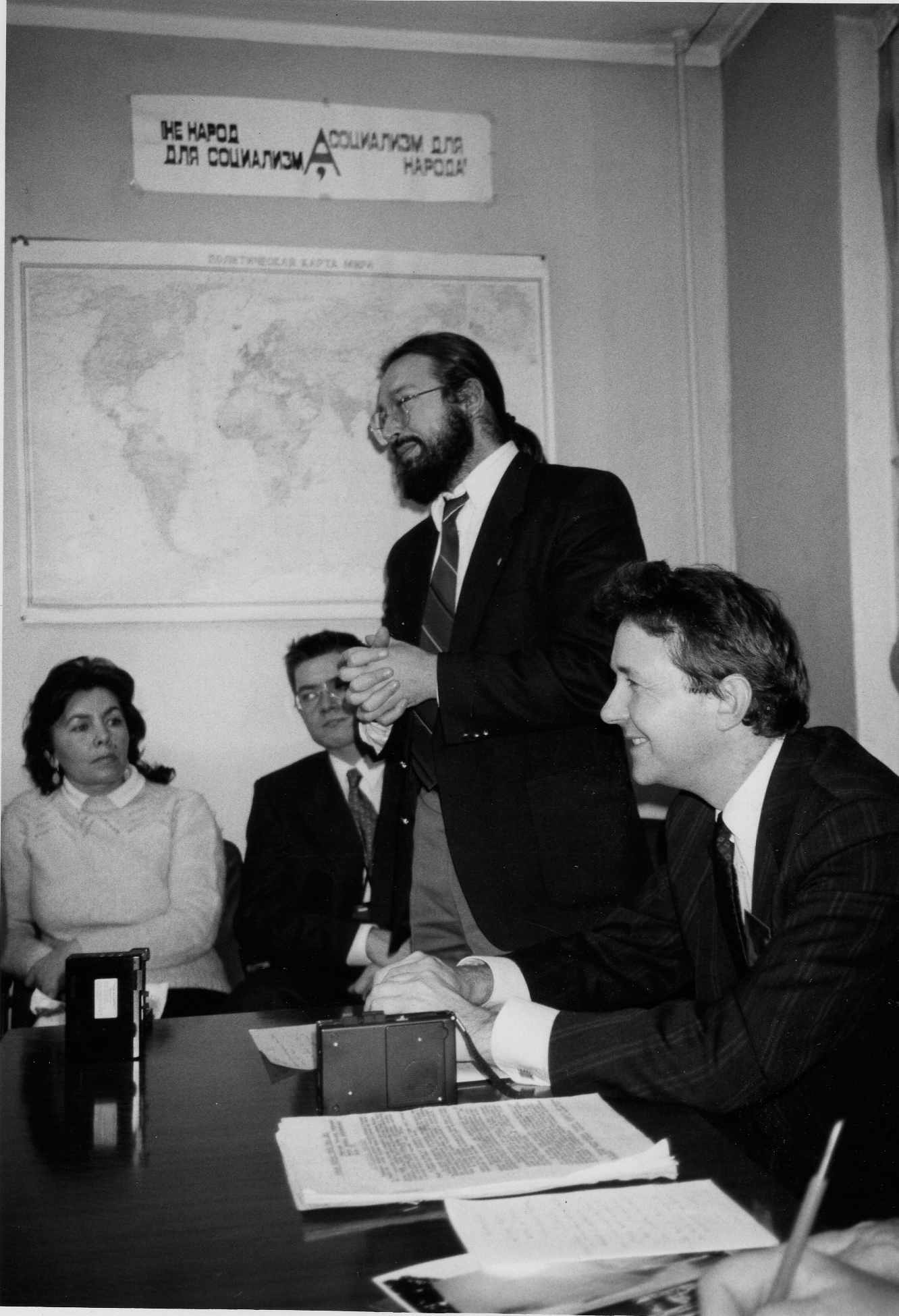

I first heard of Alexander in the early 1980s, just after I had been elected to Parliament, the human rights organisation, Jubilee Campaign, asked my support for a young Soviet dissident who had just been sent to the Gulag. His case immediately captured my interest. Ogorodnikov was not one of those protesters who carried out noisy human rights campaigns. He worked in silence, building up an underground Christian Seminar.

Three things about him fascinated me. First, in a society that was controlled by the KGB from beginning to end, he had succeeded in creating a network with branches in more than ten cities of the former Soviet Union, thereby reaching a few thousand believers − surely a feat without precedent in the history of the Soviet Union. In addition, Ogorodnikov − a young man in his twenties − called his group the “Christian” Seminar. He himself was an Orthodox convert, as were all his friends who lent their support to this initiative. But they welcomed Protestants and Catholics to their meetings as well. That ecumenical approach was also a first. Finally, his unimaginable idealism, his courage and his spirit of self-sacrifice also touched me. When given the option to leave the country, he firmly declined because he wanted to change “his” Russia from the inside out. His willingness to sacrifice himself also meant that when he was imprisoned he was parted from his wife and newborn child.

Slowly, the net closed around the group. All those responsible for keeping the Seminar alive were arrested, put through show trials and deported to Soviet camps. Inevitably, as the leader of that group Ogorodnikov was the first in the long line of detainees.

At the beginning of the eighties, news of Ogorodnikov was replaced by a disquieting silence. We could only imagine what atrocities were taking place in the Gulag. We carefully followed the publications issued by the Keston Institute in Oxford, which systematically gathered information on the dissidents via the underground press or samizdat that often travelled to the West at a snail’s pace. And as long as no death announcement was published, there was hope. Several times I myself approached the British Prime Minister and the Minister for Foreign Affairs and they made representations but it was all without results.

I vividly remember years later, at the end of 1986, when two farewell letters from Ogorodnikov reached the West − six months after they have been smuggled out of the camp in Khabarovsk. They made a huge impression on me, and they still do today, although twenty-five have elapsed. Jubilee Campaign responded to Alexander’s letters by immediately launching a campaign throughout the United Kingdom. Hundreds of thousands of posters and postcards of Alexander were distributed. I often visited Saint James Church in Westminster in the heart of London, where the Reverend Richard Rodgers and the Orthodox monk Athenasius Hart had gone on a hunger strike to obtain Ogorodnikov’s release. When Alexander was finally set free in February 1987, we threw a huge party.

Although Ogorodnikov had spent years in hell and had barely survived the horrors of the Gulag − including a few lasting physical injuries − and the KGB had destroyed his marriage, Alexander continued his struggle. What fascinated me was that he did this without any form of bitterness or hard feelings, and with that perpetual smile on his face − but at the same time with a rarely seen determination. When you’ve survived the Gulag, you’re no longer willing to compromise on anything. Alexander’s priority was to obtain religious freedom. But he also saw this as an opportunity to realize his life’s ambition: to change“his” Russia from the inside out.

As a pioneer, his accomplishments were astounding. He founded the first free school in the Soviet Union as well as the first soup kitchen and the first shelter for orphans. He also went into politics, but that step was not a success because of his unwavering scruples.

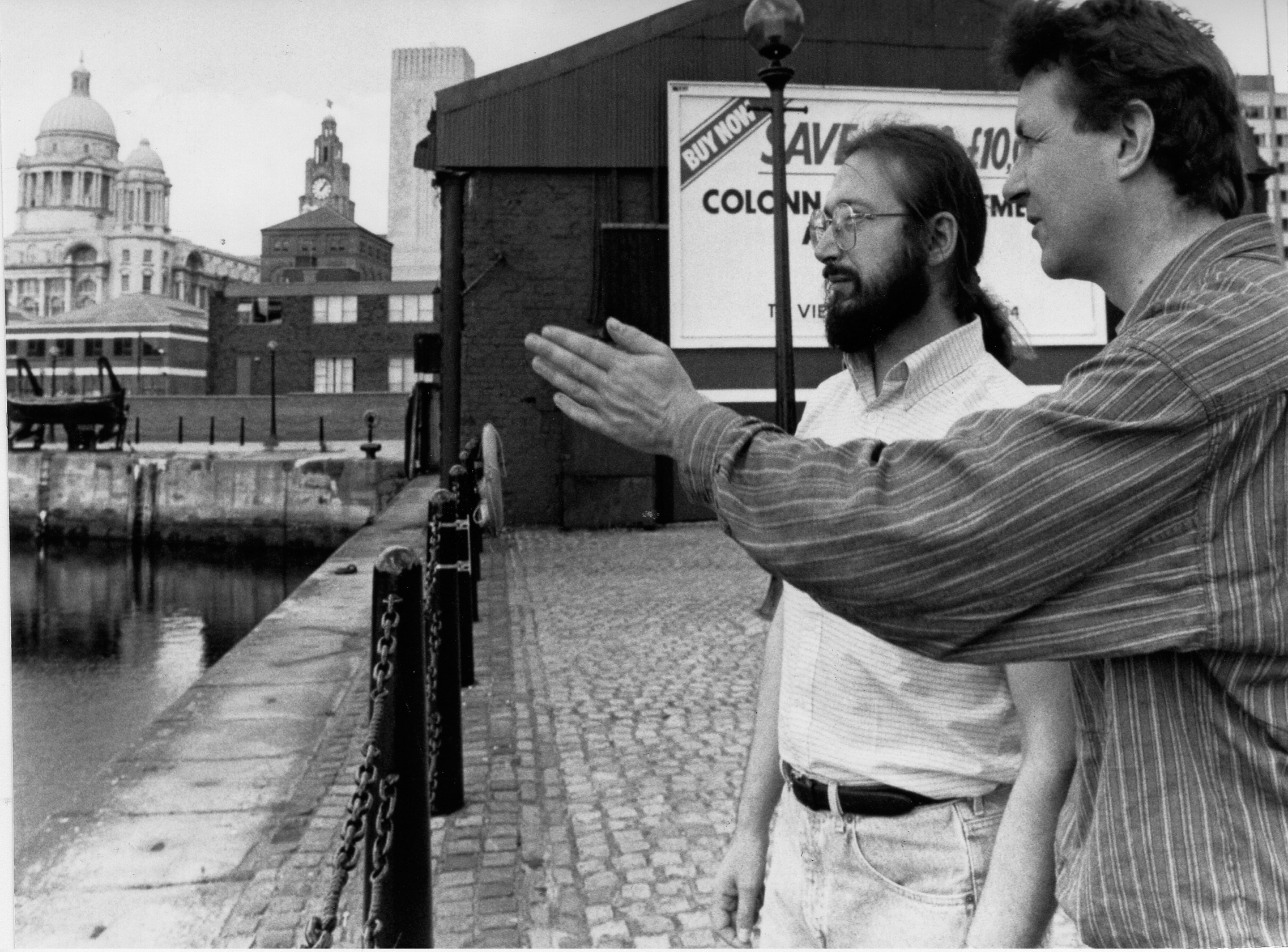

When, in 1989, he visited the West for the first time, he was my guest in Liverpool where, among other things, we visited the Beatles Museum. Alexander had told me that it was overhearing the prison guards listening to Beatles music, which had helped him to defeat the isolation in which he was kept. He told me how he had learnt some English through the music and through conversations with a prisoner in the next cell to whom he was able to have secret conversations via a broken pipe.

Alexander also visited the city’s Cathedrals – and appropriately, the Catholic church of Our Lady of Good Help, in Wavertree, where one of the Beatles, George Harrison, was baptised. At the end of Mass, Colette Carmel-Hart, the organist, played the traditional Russian anthem in his honour. He also visited a Baptist Church in Accrington – where the congregation had heard of him through their MP, the late Ken Hargreaves, and had faithfully kept him in their prayers throughout his captivity. One member of the congregation in Liverpool told him that she had his photograph in her kitchen and prayed for him daily. I think it was the first time that Alexander realized how much his courageous stand had touched people way beyond his homeland and from every walk of life.

After the extraordinary changes which came in 1989 I organized support for Alexander’s social activities, and I also helped with the delivery of the first printing press that had ever been legally imported into the Soviet Union. Our contacts have lessened over the years, but I am full of admiration when I read here that Ogorodnikov is still carrying on his struggle − often all alone. While we tend to use grand and lofty language to talk about solidarity, Ogorodnikov goes to the Moscow train stations and the metro three times a week to beg for food. And right up to the present day, this “eternal dissident” is a thorn in the side of the powers that be in the Kremlin. The fact that in 2011 his shelter in Buzhorova is wired for electricity but still is not connected to the grid, after ten years of operation, beggars the imagination. And only because he refuses to pay bribes to corrupt bureaucrats. A man who has survived the Gulag doesn’t pay bribes.

At the moment, Ogorodnikov is risking a new two-year prison sentence because a contractor who guaranteed the rebuilding of the shelter in Buzhorova in 2009 is believed to have hired illegals.

Alexander Ogorodnikov’s life story is far from over, but it testifies to a rare courage and sacrifice. It is one which deserves to be told. The struggle and suffering of the Church in the former Soviet Empire deserves to be told to all generations.

Questions about the number of children in Sudan who are (1) affected by malnutrition, and (2) no longer in education, due to the war; and about the percentage of UK aid to Sudan that (1) reaches recipients via emergency response rooms, and (2) supports emergency response rooms.

Lord Collins of Highbury, the Foreign,...